Economics Section

This brief provides an overview of the key

fiscal and economic numbers from the 2018–19 Budget.

A substantial improvement in the forecast economic and fiscal

position since the 2017–18 Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal

Outlook (MYEFO) is due largely to upward revisions to tax receipts driven by

employment and GDP growth.

The Government is now forecasting that the Budget will

return to an underlying cash balance surplus of $2.2 billion

(0.1 per cent of GDP) in 2019–20. This is one

year earlier than was forecast in the 2017–18 MYEFO. The

surplus is expected to grow to $16.6 billion (0.8 per cent of GDP) in 2020‑21

and build to at least 1 per cent of GDP over the medium term.

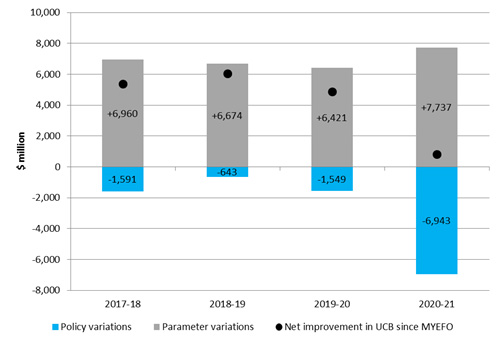

This improved fiscal position is primarily the result of

improvements in underlying economic parameters (parameter variations)—most

notably higher GDP and employment forecasts, which are expected to result in

higher taxation receipts and lower payments over the forward estimates period.

Additional policy decisions taken by the Government

in the 2018–19 Budget are expected to have a net negative

impact on the Budget over the forward estimates period, offsetting some of the

improvement in the underlying fiscal position as a result of parameter

variations.

Figure 1: impact of underlying parameter and policy

variations since the 2017–18 MYEFO

Note: UCB = underlying cash

balance

The Government’s medium-term fiscal

strategy (tax receipts <23.9%)

The Government’s medium-term fiscal strategy is to achieve

budget surpluses, on average, over the course of the economic cycle. The budget

repair strategy is designed to deliver budget surpluses building to at least 1

per cent of GDP as soon as possible, consistent with the medium-term fiscal

strategy.[1]

A new component of the Government’s medium-term strategy in

the 2018–19 Budget is a commitment to ‘maintaining a sustainable tax burden

consistent with the economic growth objective, including through maintaining

the tax-to-GDP ratio at or below 23.9 per cent of GDP’.[2]

Taxation receipts are expected to grow to 23.9 per cent of GDP by the end of

the forward estimates.

A number of commentators have questioned the economic

rationale for the adoption of this ratio; noting that, in combination with the

budget repair strategy, it gives the Government limited fiscal policy

flexibility. As a result of these self-imposed constraints on revenue, future

budget surpluses are likely to be small unless there are significant cuts to

expenditure.[3]

Views on

the economic estimates

As the improvement in the Australian government’s fiscal

position is heavily reliant on improvement in the underlying economic

parameters, this outcome is sensitive to considerable uncertainty.

A number of commentators have remarked upon the underlying

economic assumptions used in the Budget. EY and the Grattan Institute argue

that the forecasts are ‘optimistic’:

The economic growth forecasts underpinning the budget are on

the optimistic side. The budget projects a return to 3% trend growth, supported

by an ongoing recovery in business investment, stronger household spending and

a continuing public infrastructure spend.[4]

[and]

The budget forecasts for wages growth,

driving much of the planned increase in personal income tax collections, also

remain optimistic. Like the Reserve Bank, Treasurer

Scott Morrison is banking on strong growth in full-time employment translating

into higher wages. Wages growth is expected to accelerate from just over 2 per

cent a year today to 3.5 per cent by 2020–21.[5]

Deloitte highlight the uncertainties about the Budget’s

underlying assumptions:

The new plan may work, but it is vulnerable to economic and

budgetary conditions. If the economy takes a dive, then the Budget outlook

would dive alongside it. And the extended period of a

promised-but-never-materialised return to surplus may linger even longer.[6]

Global

risks

The Government acknowledges that there are also global risks

that may have a bearing on the Budget forecasts:

Globally, these risks are broadly balanced in the short term,

although they are tilted to the downside in the longer term. Key risks include

a faster-than-expected tightening of monetary policy, geopolitical tensions and

policy uncertainty in relation to trade protectionism. More broadly, a very

sharp adjustment in financial markets, which might occur from a range of

factors including elevated debt levels in a number of economies, would pose a

risk to both global and domestic activity.[7]

Headline Numbers

Economic

numbers

There are a few considerable changes to the Government’s

assumptions around major economic parameters since the 2017–18 MYEFO (see Table

1). These upwards revisions are predominately in the 2017–18 financial year,

which means that they have cumulative effects across the forward estimates

period. The changes are as follows:

- Real GDP growth for 2017–18 has been revised up to 2.75 per cent

from 2.5 per cent.

- Nominal GDP growth in 2017–18 has been revised up to 4.25 per

cent from 3.5 per cent (but revised down for 2018–19 by 0.25 per cent).

- Employment growth in 2017–18 has been revised upwards by 1 per

cent to 2.75 per cent.

Government forecasts of growth in the Wage Price Index are

unchanged.

Table 1: growth in key economic

parameters at 2018–19 Budget relative to 2017–18 MYEFO

| |

Outcomes |

Forecasts |

Projections |

|

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

2020–21 |

2021–22 |

| Real GDP |

2.1 |

2.75 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

| Change since MYEFO |

0.1 |

0.25 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

n/a |

| Nominal GDP |

5.9 |

4.25 |

3.75 |

4.75 |

4.5 |

4.5 |

| Change since MYEFO |

0.1 |

0.75 |

–0.25 |

0.25 |

–0.25 |

n/a |

| CPI |

1.9 |

2 |

2.25 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

| Change since MYEFO |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

n/a |

| Wage Price Index |

1.9 |

2.25 |

2.75 |

3.25 |

3.5 |

3.5 |

| Change since MYEFO |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

n/a |

| Employment |

1.9 |

2.75 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.25 |

1.25 |

| Change since MYEFO |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0.25 |

0 |

n/a |

| Unemployment |

5.6 |

5.5 |

5.25 |

5.25 |

5.25 |

5 |

| Change since MYEFO |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

n/a |

Sources: Australian

Government, Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook 2017–18, p. 3; Australian Government, Budget strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1:

2018–19, Statement 1, p. 1-10.

The Reserve Bank of Australia has forecast year-end real GDP

growth of 2.75 per cent for 2017–18, but it expects stronger growth of 3.5 per

cent in 2018–19 before falling to 3.0 per cent in 2019–20.[8]

Fiscal numbers

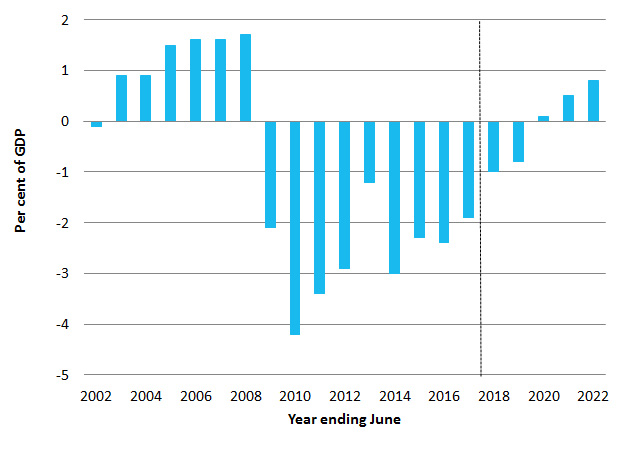

The underlying cash balance is forecast to fall to a

deficit of $14.5 billion (0.8 per cent of GDP) in 2018–19, and to return to a surplus

of $2.2 billion (0.1 per cent of GDP) in 2019–20 (see Table 2 and Figure 2).

Table 2: underlying cash balance

| |

Actual |

Estimates |

Projections |

|

| |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

2020–21 |

2021–22 |

Total |

| Underlying cash balance ($b) |

–18.2 |

–14.5 |

2.2 |

11.0 |

16.6 |

15.3 |

| Per cent of GDP |

–1.0 |

–0.8 |

0.1 |

0.5 |

0.8 |

|

Source: Australian

Government, Budget strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1:

2018–19, Statement 3, p. 3-5.

Figure 2: underlying cash balance

Source: Australian

Government, Budget strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1:

2018–19, Statement 11, Historical

Australian Government Data, Table 1, p. 11-6.

The structural budget balance—which removes those

factors which have a temporary impact on revenues and expenditures—is estimated

to improve from a deficit of 1.25 per cent of GDP in 2018–19 to a series of

surpluses from 2020–21.

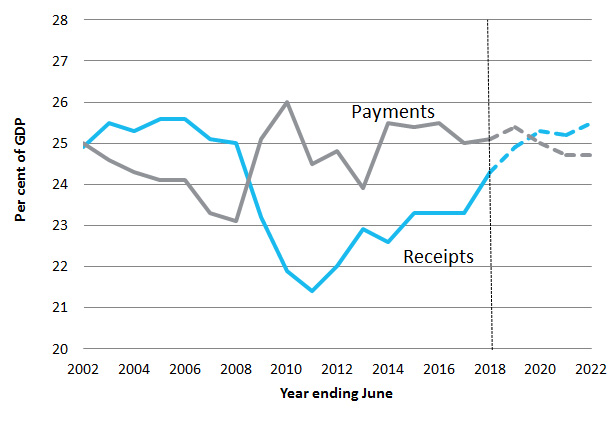

Total general government sector receipts are

estimated to be $473.7 billion (24.9 per cent of GDP) in 2018–19, rising to

$554.0 billion (25.5 per cent of GDP) in 2021–22 (see Table 3 and Figure 3).

Table 3: total general government sector receipts

| |

Actual |

Estimates |

Projections |

|

| |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

2020–21 |

2021–22 |

Total |

| Receipts

($ b) |

445.1 |

473.7 |

503.7 |

525.5 |

554.0 |

2 056.8 |

| Per

cent of GDP |

24.3 |

24.9 |

25.3 |

25.2 |

25.5 |

|

Source: Australian

Government, Budget strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1:

2018–19, Statement 3, p. 3-10.

Figure 3: payments and receipts

Source: Australian

Government, Budget strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1:

2018–19, Statement 11: Historical

Australian Government Data, Table 1, p. 11-6.

Tax receipts are estimated to be $440.5 billion (23.1

per cent of GDP) in 2018–19 and $465.5 billion (23.3 per cent of GDP) in

2019–20, increasing to a projected $519.6 billion (23.9 per cent of GDP) by

2021–22. This projection is consistent with the updated medium-term fiscal

strategy, which includes the maintenance of a tax-to-GDP ratio at or below 23.9

per cent of GDP.

General government sector payments are estimated to

fall as a share of GDP, from 25.4 per cent of GDP in 2018–19 to 24.7 per cent

of GDP in 2021–22 (see Table 4 and Figure 3).

Table 4: general government sector

payments

| |

Actual |

Estimates |

|

Projections |

|

|

| |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

2020–21 |

2021–22 |

Total |

| Payments

($b) |

459.9 |

484.6 |

497.5 |

514.5 |

537.3 |

2 034.0 |

| Per

cent of GDP |

25.1 |

25.4 |

25.0 |

24.7 |

24.7 |

|

Source: Australian

Government, Budget strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1:

2018–19, Statement 3, p. 3-10.

General government net capital investment is expected

to be $4.9 billion in 2018–19 (0.3 per cent of GDP), $4.8 billion higher than

net capital investment in 2017–18. This change is due to funding associated

with the implementation of the 2016 Defence White Paper.[9]

Over the four years to 2021–22, net capital investment in defence is projected

to total $25.3 billion. Net capital investment in almost all other functions is

projected to decline.[10]

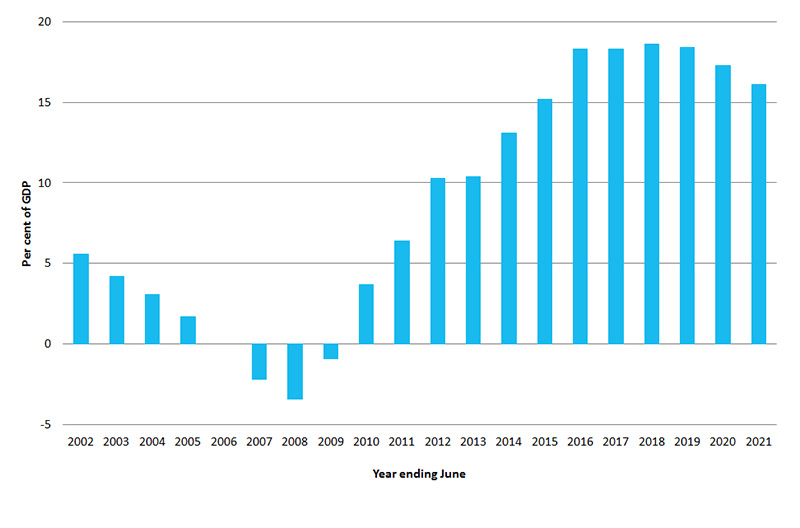

General government sector net debt is estimated to

reach 18.4 per cent of GDP in 2018–19, before falling 14.7 per cent of GDP in

2021–22. It is projected to continue falling to 5.2 per cent of GDP by 2027–28

(see Table 5 and Figure 4).[11]

Table 5: net and gross debt

| |

Actual |

Estimates |

Projections |

| |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

2020–21 |

2021–22 |

|

| Net

debt ($b) |

341.0 |

349.9 |

344.0 |

334.3 |

319.3 |

|

| Per

cent of GDP |

18.6 |

18.4 |

17.3 |

16.1 |

14.7 |

|

| Gross

debt ($b) |

533.0 |

561.0 |

579.0 |

566.0 |

578.0 |

|

| Per

cent of GDP |

29.0 |

29.5 |

29.0 |

27.2 |

26.6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Australian

Government, Budget strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1:

2018–19, Statement 11, p. 11-12

and p. 11-14.

Figure 4: net debt

Source: Australian

Government, Budget strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1:

2018–19, Statement 11: Historical

Australian Government Data, Table 4, p. 11-12.

Gross debt (the face value of CGS on issue) is

projected to rise from 29.4 per cent of GDP in 2018–19 to 26.6 per cent of GDP

by the end of the forward estimates, before falling to $532 billion by

2028–29 (see Table 5).[12]

General government sector net interest payments are

estimated to fall from $14.5 billion (0.8 per cent of GDP) in 2018–19 to $12.2

billion (0.6 per cent of GDP) in 2019–20, remaining at 0.6 per cent of GDP up

to 2021–22 (see Table 6).[13]

Net financial worth, an indicator of fiscal sustainability, has improved

over the forward estimates relative to 2017–18 MYEFO. It is estimated to be

25.4 per cent of GDP in 2018–19, improving marginally to 24.2 per cent of GDP

in 2019–20. Another component of the medium term fiscal strategy is ‘improving

net financial worth over time’. Government projections suggest that net

financial worth will be 7.5 per cent of GDP by 2028–29.[14]

Table 6: net financial worth and

net interest payments

| |

Actual |

Estimates |

Projections |

| |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

2020–21 |

2021–22 |

| Net

interest payments ($ billion) |

13.1 |

14.5 |

12.2 |

12.4 |

12.2 |

| Per

cent of GDP |

0.7 |

0.8 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

| Net

financial worth ($ billion) |

–466.3 |

–482.9 |

–482.1 |

–471.3 |

–453.9 |

| Per

cent of GDP |

–25.4 |

–25.4 |

–24.2 |

–22.6 |

–20.9 |

Source: Australian

Government, Budget strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1:

2018–19, Statement 3, p. 3-16.

Key revenue and expense measures

Table 7 lists the major revenue measures—and Table 8, the

major expense measures—with a significant impact in the 2018–19 Budget.

Table 7: major policies—revenue

measures

| |

2017–18 ($m) |

2018–19 ($m) |

2019–20 ($m) |

2020–21 ($m) |

2021–22 ($m) |

Total ($m) |

| Personal

Income Tax Plan |

– |

–360 |

–4 120 |

–4 420 |

–4 500 |

–13 400 |

| Personal

Income Tax – retaining the

Medicare levy rate at 2 per cent |

– |

–400 |

–3 550 |

–4 250 |

–4 600 |

–12 800 |

| Black

Economy Package – Combatting

Illicit Tobacco |

– |

–15 |

3 251 |

148 |

193 |

3 577 |

| Better

targeting the Research and Development Tax Incentive |

– |

314 |

641 |

764 |

719 |

2 438 |

| Black

Economy Package – New and

enhanced ATO enforcement against the Black Economy |

– |

340 |

467 |

533 |

578 |

1 917 |

| Personal

Income Tax - ensuring individuals meet their tax obligations |

– |

180 |

258 |

277 |

277 |

991 |

| Protecting

Your Super Package – changes to

insurance in superannuation |

– |

– |

224 |

228 |

245 |

697 |

| A

firm stance on tax and superannuation debts |

– |

–149 |

–152 |

–156 |

–160 |

–617 |

| Black

Economy Package – further

expansion of taxable payments reporting |

– |

–4 |

47 |

264 |

299 |

606 |

| Superannuation

– better integrity over

deductions for personal contributions |

– |

89 |

109 |

110 |

120 |

427 |

Source: Australian

Government, Budget Measures: budget paper no. 2: 2018–19, Table 1, pp. 1–6.

Table 8: major policies—expense measures

| |

2017–18 ($m) |

2018–19 ($m) |

2019–20 ($m) |

2020–21 ($m) |

2021–22 ($m) |

Total ($m) |

| Supporting

Our Hospitals – National Health Agreement – public

hospital funding |

– |

–50 |

– |

–331 |

–597 |

–977 |

| Pharmaceutical

Benefits Scheme – new and amended listings |

–17 |

–175 |

–221 |

–255 |

–102 |

–770 |

| Great

Barrier Reef 2050 Partnership Program |

–444 |

–10 |

–5 |

–8 |

–11 |

–478 |

| Remote

Indigenous Housing in the Northern Territory |

– |

–110 |

–110 |

–110 |

–110 |

–440 |

| National

Research Infrastructure Investment Plan – implementation of Government response |

–199 |

–6 |

–26 |

–76 |

–87 |

–393 |

| Funding

to Boost Services in the Northern Territory |

–260 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

–260 |

| More

Choices for a Longer Life – finances for a longer life |

0 |

–21 |

–93 |

–75 |

–70 |

–259 |

| Managing

the Skilling Australians Fund – revised implementation arrangements |

–250 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

–250 |

| National

School Chaplaincy Programme – continuation |

– |

–62 |

–62 |

–62 |

–62 |

–247 |

| Building

Better Regions Fund – round three |

– |

–40 |

–108 |

–48 |

–10 |

–207 |

Source: Australian

Government, Budget Measures: budget paper no. 2: 2018–19, Table 2, pp. 47–68.

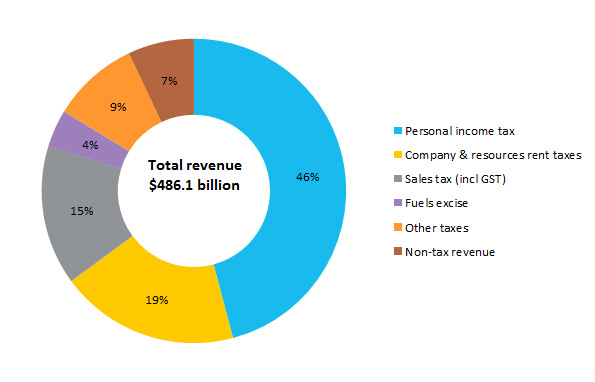

Revenue 2018–19

| |

$b |

Percentage |

| Personal

income tax |

222.9 |

45.9 |

| Company

& resource rent taxes |

92.6 |

19.0 |

| Sales

tax (incl. GST) |

72.1 |

14.8 |

| Fuels

excise |

19.5 |

4.0 |

| Other

taxes |

44.9 |

9.2 |

| Non-tax

revenue |

34.1 |

7.0 |

| Total |

486.1 |

100.0 |

|

Figure

5: revenue in 2018–19

Source: Australian Government, Budget strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1:

2018–19, Budget overview, 8 May

2018, Statement 6, Appendix A, p. 6-50.

|

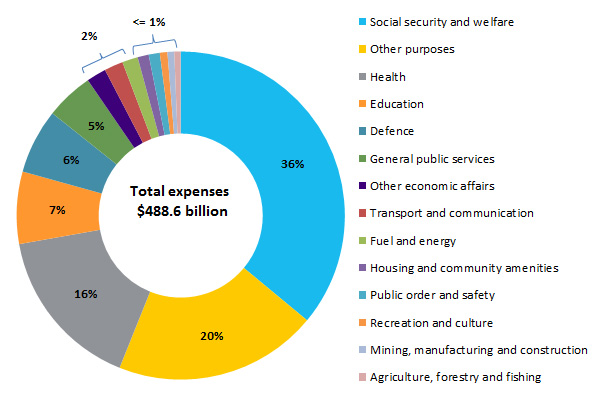

Government expenses by function 2018–19

| Function |

$b |

Percentage |

| Social

security and welfare |

176.0 |

36.0 |

| Health |

78.8 |

16.1 |

| Education |

34.7 |

7.1 |

| Defence |

31.2 |

6.4 |

| General

public services |

23.1 |

4.7 |

| All

other functions |

46.8 |

9.6 |

| Other

purposes |

98.0 |

20.0 |

| Total |

488.6 |

100.0 |

|

Figure 6: expenses by function

Source: Australian Government, Budget strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1:

2018–19, Budget overview, 8 May

2018, Statement 5, Table 10, p. 5-21.

|

[1] Australian

Government, Budget

strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1: 2018–19, Statement 3, p. 3-7.

[2].

Ibid.

[3].

D Richardson and B Browne, The

arbitrary 23.9 per cent tax revenue to GDP figure: from a convenient assumption

to a ‘speed limit’, Australia Institute, Briefing note, April 2018;

National Australia Bank (NAB), Federal

Budget 2018–19, May 2018.

[4].

EY, Federal

Budget 2018: Punting on growth, May 2018.

[5].

B Coates and D Wood (Grattan Institute), ‘Budget

2018: built on good fortune, relying on luck’, Inside Story, 9 May

2018.

[6].

Deloitte, The

intersection of politics and prudence: Australian Federal Budget 2018–19,

May 2018.

[7].

Australian Government, Budget

strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1: 2018–19, Statement 1, p. 1-9.

[8].

Reserve Bank of Australia, Statement

on Monetary Policy, May 2018.

[9].

Australian Government, Budget

strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1: 2018–19, Statement 6, p. 6-46.

[10].

Ibid., Table 20, p. 6-48.

[11].

Ibid., Statement 11, p. 11-12.

[12].

Ibid., Statement 3, p. 3-16.

[13].

Ibid.

[14].

Ibid., p. 3-17.

All online articles accessed May 2018

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.

In essence, you are free to copy and communicate this work in its current form for all non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the work to the author and abide by the other licence terms. The work cannot be adapted or modified in any way. Content from this publication should be attributed in the following way: Author(s), Title of publication, Series Name and No, Publisher, Date.

To the extent that copyright subsists in third party quotes it remains with the original owner and permission may be required to reuse the material.

Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of the publication are welcome to webmanager@aph.gov.au.

This work has been prepared to support the work of the Australian Parliament using information available at the time of production. The views expressed do not reflect an official position of the Parliamentary Library, nor do they constitute professional legal opinion.

Any concerns or complaints should be directed to the Parliamentary Librarian. Parliamentary Library staff are available to discuss the contents of publications with Senators and Members and their staff. To access this service, clients may contact the author or the Library‘s Central Enquiry Point for referral.