Helen Portillo-Castro

Housing affordability for both renters and purchasers has

declined significantly in recent decades, leading policymakers to have considered

the contributing factors through numerous inquiries.[1]

In the 2017–18 Budget, the Government proposes a number of

measures to address this social and economic issue. Broadly speaking, the

Government’s three-pronged approach seeks to improve the supply of housing,

including affordable housing, to support first home buyers and dampen demand

from domestic and foreign investors.

There are over 12 interrelated measures in the Government’s

housing affordability package.[2] This brief focuses on

those taxation measures with the greatest impact on revenue and expenditure,

and measures that may represent a policy shift in relation to superannuation. A

related Budget Review article, ‘Social Housing and Homelessness’, explains

the measures that provide mechanisms for investment in the social housing

sector.[3]

Changes to tax arrangements and

deductions

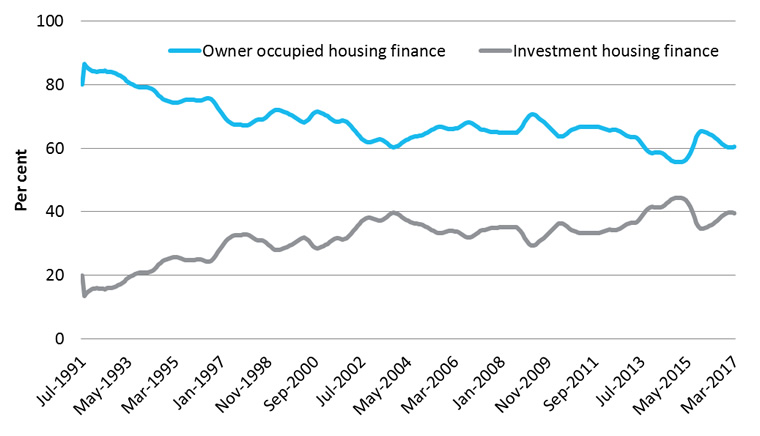

The share of new housing finance flowing to investors has

increased over recent years, as illustrated in Figure 1. Increasing investor

involvement in the market is widely considered to be a driver in increasing housing

prices in some geographical markets.[4]

Figure 1: Share of new housing finance for dwellings, 1991–2017

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Housing finance, Australia, March 2017, cat. no. 5609.0, Table 11.

Note: includes re-financing.

The Treasurer has announced several measures to increase the

tax burden on residential property investors and to reduce the incentive for

foreign investors to purchase residential property in Australia. The aggregated

projected revenue from these measures is in excess of $1.3 billion over

the forward estimates.[5]

Proposed restrictions on foreign

investors

Currently, there are several

restrictions on foreign ownership of residential property in Australia. The

Reserve Bank of Australia states that ‘the limited and partial data available

from the Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) suggest that approvals for all

non-residents applying to purchase residential property have increased

substantially of late’.[6] Foreign investment

approvals in real estate increased from 11,668 approvals in 2012–13 to 40,141

in 2015–16.[7] More than three-quarters

of approved FIRB applications were for housing stock valued at less than

$1 million.[8]

The existing system for

new dwelling exemption certificates, administered by the FIRB, ‘act as

pre-approval’ for property developers to sell new dwellings in a specified

development to foreign investors. The Government proposes to limit foreign

ownership of dwellings in new developments by introducing a new condition to

the existing certification scheme. From Budget night, the certificates will

include a 50 per cent cap on foreign ownership in multi-storey

development projects that have obtained development approval from the relevant

government authority.[9] This measure has no

revenue impact in the forward estimates, but is to ‘ensure a minimum proportion

of developments are available for Australians to purchase [and to send] a clear

message that the Government expects developments to increase the housing stock

for Australian purchasers’.[10]

The Government also

proposes to place a charge on vacant property ‘equivalent to the relevant

foreign investment application fee’ that will be levied on ‘foreign owners of

residential property where the property is not occupied or genuinely available

on the rental market for at least six months per year’.[11]

Where otherwise vacant properties are made available for rent, this is expected

to increase supply in the private rental market.[12]

The measure is expected to raise $16.3 million in revenue over the forward estimates.

The Budget includes several changes to increase the rate of

capital gains tax (CGT) faced by foreign investors and temporary tax residents.[13]

This is projected to raise $581 million over the forward estimates.

Reducing allowable deductions for property

investors

The Treasurer has announced restrictions on the deductions

that property investors can claim. The following changes are expected to

increase revenue by $800 million over the forward estimates:

- From 1 July 2017, investors will be able to claim ‘plant and

equipment depreciation deductions’ only if they are actually incurred. This measure

is intended to prevent items ‘being depreciated by successive investors in

excess of their actual value’, and is expected to increase revenue by $260 million

over the forward estimates.[14]

- From 1 July 2017, travel expenses related to ‘inspecting,

maintaining or collecting rent for a residential rental property’ will no

longer be deductible. This measure is expected to increase revenue by $540 million

over the forward estimates.[15]

The Australian Tax Office

publishes data on the number of individuals claiming certain deductions

associated with their rental income. In 2014–15, travel expenses reported in

individual rental property schedules comprised $456 million, while $2.6 billion

in ‘plant depreciation’ was reported (comprising depreciating assets such as

stoves and air conditioners).

Measures affecting superannuation

Under the proposed budget measures

related to housing affordability, both younger and older Australians will be eligible

to use the amount of their superannuation derived from voluntary superannuation

contributions differently.

Saving for a deposit for a first

home—addressing the ‘deposit hurdle’

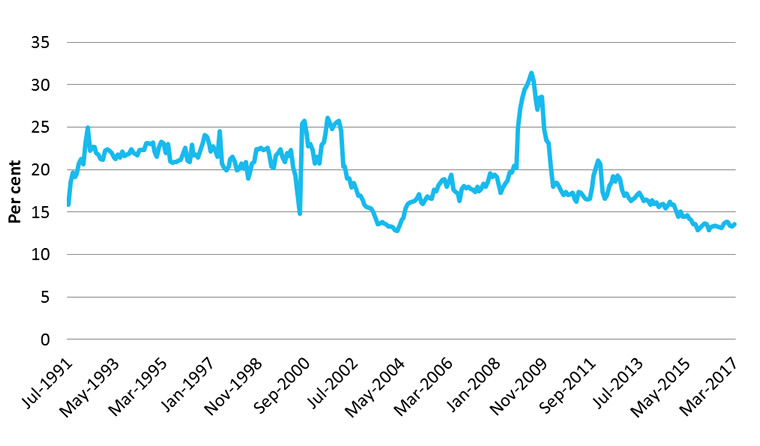

First home buyers represent a smaller proportion of the

market than other purchasers seeking home loans, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: First home buyer finance

commitments, percentage as a total of all new housing finance

Source: ABS, Housing finance, Australia, March 2017, cat. no. 5609.0, Table

9a.

First home buyers are in different

position from established home owners, who typically have sufficient equity in

their homes and do not need additional money for a deposit. As house prices

rise in some places, and as lenders tighten lending requirements, including

minimum deposits, the amount required by first home buyers increases. The

challenge of accumulating a deposit has become known as the ‘deposit hurdle’.[16]

The First Home Super Saver Scheme introduced in the Budget

‘to encourage home ownership’ is intended to address this financial barrier.[17]

Under the proposal, first home buyers will be able to withdraw voluntary

superannuation contributions made after 1 July 2017, in order to contribute to

a deposit for a first home. Withdrawals can be made from 1 July 2018, up to a

limit of $30,000, and will be taxed at an individual’s marginal rate, less 30

per cent. The measure is expected to cost $250 million over the forward

estimates.

An earlier policy to support first home buyers, the First

Home Saver Account (FHSA), was introduced in 2008, and provided concessional

savings and government co-contributions. Banks criticised FHSAs because of the

additional administration involved, and FHSAs were closed in 2015 after lower

than expected take-up.[18]

Encouraging downsizing: tax

treatment of assets

The Budget introduces a scheme that allows individuals over

65 to make non-concessional contributions into their superannuation from the proceeds

from the sale of their home. This is intended to reduce ‘a barrier to

downsizing for older people’, to ‘enable more effective use of the housing

stock by freeing up larger homes for younger, growing families’.[19]

The measure will apply from 1 July 2018. The contribution will be capped at

$300,000 per person (whether a person is partnered or not) and be exempt from tests

otherwise applicable to non-concessional contributions.[20]

The measure will come at a cost to revenue of $30 million over the forward

estimates.

The 2013–14 Budget provided for a pilot to incentivise

downsizing through a means test exemption for age pension recipients.[21]

This pilot never commenced, however, due to a reversal of the funding in the

subsequent 2014–15 Budget as a result of a recommendation from the National

Commission of Audit.[22] The Government cited a

lack of evidence that the measure would achieve its objective.[23]

Commentary prior to the release of this year’s Budget pointed to evidence which

shows that non-financial considerations are more significant than financial

barriers to downsizing among older Australians.[24]

Other measures in the housing

affordability package

The Treasurer has announced a range of other measures to

increase housing supply. These include:

- encouraging managed investment trusts (MITs) to ‘acquire,

construct, or redevelop affordable housing to hold for rent’.[25]

MITs ‘allow investors to pool their funds to invest in primarily passive

investments and have them managed by a professional manager’.[26]

MITs must derive 80 per cent of their assessable income from affordable

housing, and the housing must be available for rent for at least 10 years[27]

-

increasing the capital gains tax (CGT) discount for affordable

housing—that is, housing rented to low-to moderate-income tenants at below-market

rates through a registered community housing provider. Investors will be

eligible for a higher CGT discount of 60 per cent (instead of the standard

50 per cent discount) when the investment is held for three years. Individual

investors who are Australian residents will be eligible for a CGT discount

above 60 per cent when placing their investment through an MIT[28]

- trialling incentive payments under the Western Sydney City Deal,

‘to support planning and zoning reform’.[29] The amount of funding

under the Western Sydney City Deal will depend on its final form, and the

incentive payments that are made.

- establishing a National Housing Infrastructure Facility (NHIF) to

provide financial assistance to local government from 2018–19 ‘for

infrastructure that supports new housing, particularly affordable housing’.[30]

An initial $118 million will come from the Contingency Reserve to fund

grants and ‘the fiscal balance impact of concessional loans’.[31]

The NHIF proposal includes an unquantified revenue impact

tied to interest on concessional loans and is contingent on the establishment

of the National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation, which will also

administer the housing bond aggregator, an explanation of which can be found in

the Budget Review article on ‘Social Housing and Homelessness’.

Responses

Economists

Economists have questioned whether this package of measures

will have a significant impact. The Grattan Institute described the package as

‘a grab-bag of “easy solutions”’, and argued that ‘a few of them sound good;

fewer still will make a difference’.[32] KPMG chief economist Brendan

Rynne said that ‘it’s not [enough]’, and argued that other tax changes would be

more effective, including reducing the CGT discount from 50 to 25 per cent.[33]

Economist Saul Eslake supported some of the supply measures targeting

affordable housing, but argued that overall, the package ‘won’t make a huge

difference’.[34]

Industry and other stakeholders

The Australian Council of Social Services welcomed what it

called ‘first steps to address housing affordability’, but argued that ‘the

extension of super tax breaks to people buying a first home or downsizing is a

backward step that will increase house prices and waste public revenue’.[35]

The Property Council of Australia supported the package in

general, but argued that ‘the initiatives targeting foreigners will damage

Australia’s reputation and will do nothing to help housing affordability’.[36]

The Housing Industry Association described the ‘focus on

housing’ as ‘an important step in addressing the complex housing affordability

challenge’, but argued that restrictions on foreign investors would reduce

investment.[37]

[1].

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Housing

occupancy and costs, 2013–14, cat.no. 4130.0, 16 October 2015. See also M Thomas and A Hall, ‘Housing affordability in Australia’, Briefing book: key issues

for the 45th Parliament,

Parliamentary Library, Canberra,

2016, pp. 86–89; T Dale, ‘Housing

affordability and home ownership: previous inquiries and reports’,

FlagPost, Parliamentary Library blog, 29 March 2017.

[2].

These measures are entitled as ‘Reducing pressure on housing

affordability’ combined with the following sub-titles and appearing in Australian Government, Budget measures: budget paper no. 2: 2017–18, 2017 in the following order: ‘affordable housing through

Managed Investment Trusts’; ‘annual charge on foreign owners of underutilised

residential property’; ‘capital gains tax changes for foreign investors’; ‘contributing

the proceeds of downsizing to superannuation’; ‘disallow the deduction of

travel expenses for residential rental property’; ‘expanding tax incentives for

investments in affordable housing’; ‘first home saver scheme’; ‘limit plant and

equipment depreciation outlays actually incurred to investors’; ‘restrict

foreign ownership in new developments to no more than 50 per cent’;

‘Western Sydney’; ‘a new National Housing and Homelessness Agreement’; ‘Social

Impact Investments’; ‘support for the Homes for Homes Initiative’;

‘establishment of the National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation’; and

‘National Housing Infrastructure Facility’. (There are additional measures that

a related but do not bear the same title, such as ‘Social Impact Investing

Market—trials’.)

[3].

M Thomas, ‘Social

housing and homelessness’, Budget review 2017–18, Research paper

series, 2016–17, Parliamentary Library, Canberra, 2017.

[4].

Investors in this context include established Australian households

with one or more residential investment properties. See, for example, J Yates,

‘Housing

in Australia in the 2000s: on the agenda too late?’, in H Gerard and J

Kearns, eds, The Australian economy in the 2000s, Reserve Bank of

Australia (RBA) conference papers, RBA, Sydney, December 2011. Investor

activity is not considered in terms of cause and effect in relation to house

prices, but rather as an amplifier to underlying supply and demand dynamics,

particularly in major cities: see P Lowe (Governor, RBA), Household

debt, housing prices and resilience: speech to the Economic Society of

Australia (Queensland) business lunch, Brisbane, media release,

4 May 2017.

[5].

The budget figures in this brief have been taken from the following

document unless otherwise sourced: Budget measures: budget paper no. 2: 2017–18, op.cit.

[6].

RBA, ‘Box B: Chinese demand for Australian property’, Financial Stability Review, RBA, April 2016.

[7].

Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB), Annual

report 2015–16, FIRB, p. 34.

[8].

Ibid., p. 20. Unfortunately, there is limited publicly available

data on the proportion of the dwelling stock currently owned by non-residents:

estimates around proportion of new housing supply purchases are based on

freedom of information requests. See, for example, M Robin, ‘Chinese

buyers to prop up Australian housing market: Credit Suisse’, The Sydney Morning Herald

(online), 24 March 2017.

[9].

Budget measures: budget paper no. 2: 2017–18, op.cit., p. 31; see also FIRB, Residential real estate—new

dwelling exemption certificate, Guidance note 8,

updated 9 May 2017.

[10].

Budget measures: budget paper no. 2: 2017–18, op.cit., p. 31.

[11].

Ibid., p. 27.

[12].

Ascertaining an accurate estimate for vacant dwellings in relation to supply

of housing stock presents methodological difficulties: see, for example,

Australian Government, National

Housing Supply Council: Housing supply and affordability issues 2012–13,

Treasury, Canberra, 2013, pp. 119–24.

[13].

The primary test for being a resident or non-resident for tax purposes is

the ‘resides’ test. This test looks at a range of factors to determine whether

Australia is your usual abode, including intention of stay, location of assets

and family and business ties. In this context, the 2012–13 Budget removed the

50 per cent capital gains tax discount for non-residents on capital gains

accrued after 8 May 2012. Further detail, including links to guidance

notes, is available in FIRB, ‘Budget

2017 changes’, FIRB website.

[14].

Budget measures: budget paper no. 2: 2017–18,

op. cit., pp. 30–31.

[15].

Ibid., p. 29.

[16].

CoreLogic, Housing affordability report, CoreLogic Australia,

Sydney, December 2016.

[17].

Budget measures: budget paper no. 2: 2017–18,

op. cit., p. 30.

[18].

T Dale, ‘First

Home Saver Accounts scheme closure’, FlagPost, Parliamentary Library blog, 18 June 2014.

[19].

Budget measures: budget paper no. 2: 2017–18,

op. cit., p. 28.

[20].

This measure can be read alongside changes to non-concessional

contributions due to come into effect in the 2017–18 financial year in

Australian Tax Office (ATO), ‘Change

to non-concessional contributions cap’, ATO website, 5 May 2017.

[21].

Australian Government, Budget

measures: budget paper no. 2: 2013–14, 2013, p. 152.

[22].

Australian Government, Budget

measures: budget paper no. 2: 2014–15, 2014, p. 201; J Hockey

(Treasurer) and M Cormann (Minister for Finance), Our

response to the National Commission of Audit report, joint media

release, 13 May 2014.

[23].

K Andrews (Minister for Social Services), Budget

2014: delivering our commitments to Australian seniors, media release,

13 May 2014.

[24].

B Coates and J Daley, ‘Why

older Australians don’t downsize and the limits to what the government can do

about it’, The Conversation, 5 May 2017; see also B Judd

et al., Downsizing

amongst older Australians, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute

(AHURI), final report no. 214, AHURI, Melbourne, January 2014.

[25].

S Morrison (Treasurer), Budget

2017: address to the ACOSS post-budget breakfast, Sydney, media

release, 15 May 2017.

[26].

Budget measures: budget paper no. 2: 2017–18,

op. cit., p. 26. See also, M Felsman, ‘Difference

between active and passive investing’, Investor Update, Australian

Securities Exchange newsletter, August 2016.

[27].

Ibid.

[28].

Ibid., p. 29.

[29].

Ibid., p. 142; see also S Morrison (Treasurer) and A Taylor (Minister for

Cities), Budget

2017: Western Sydney housing package: more homes in right locations,

media release, 16 May 2017.

[30].

Budget measures: budget paper no. 2: 2017–18,

op. cit., p. 170.

[31].

Ibid.; Australian Government, Portfolio

budget statements 2017–18: budget related paper no. 1.16: Treasury Portfolio,

p. 21.

[32].

J Daley and B Coates, 'Another

lost opportunity for housing affordability', Inside Story, 10 May

2017.

[33].

G Hutchens, ‘Budget

2017: Coalition’s housing package won’t fix affordability crisis, experts say’,

The Guardian (online), 10 May 2017.

[34].

E Alberici, ‘Saul

Eslake and Lenore Taylor dissect the 2017 federal Budget’, Lateline,

Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), 9 May 2017.

[35].

Australian Council of Social Service, Welcome

change of tack in health education and housing, but vilification of people who

are unemployed continues, media release, 9 May 2017.

[36].

Property Council of Australia, Budget

tackles fundamentals of housing affordability, media release, 9 May 2017.

[37].

Housing Industry Association, Budget

is a step to housing affordability, media release, 9 May 2017.

All online articles accessed May 2017.

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.

In essence, you are free to copy and communicate this work in its current form for all non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the work to the author and abide by the other licence terms. The work cannot be adapted or modified in any way. Content from this publication should be attributed in the following way: Author(s), Title of publication, Series Name and No, Publisher, Date.

To the extent that copyright subsists in third party quotes it remains with the original owner and permission may be required to reuse the material.

Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of the publication are welcome to webmanager@aph.gov.au.

This work has been prepared to support the work of the Australian Parliament using information available at the time of production. The views expressed do not reflect an official position of the Parliamentary Library, nor do they constitute professional legal opinion.

Any concerns or complaints should be directed to the Parliamentary Librarian. Parliamentary Library staff are available to discuss the contents of publications with Senators and Members and their staff. To access this service, clients may contact the author or the Library‘s Central Enquiry Point for referral.