Emma Vines and Rebecca Storen, Social

Policy

Key issue

The 46th Parliament oversaw the launch of new strategies and plans that respond to challenges related to the sustainability, regulation and support of the health workforce. However, concerns continue to arise over these and other issues, such as the registration, distribution, training and retention of healthcare professionals.

The health workforce will need to grow to meet the anticipated demand of an ageing population with increased incidence of comorbidities. Now more than ever, the existing workforce is under sustained pressure due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

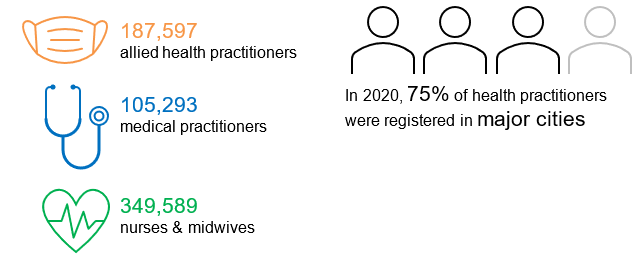

In 2020, there were:

Source: Department of Health, Health

Workforce Data – Dashboard, 2021.

Responsibility for health workforce planning and

most regulation is shared by the Australian and state and territory governments,

with input, especially for training and education, from other organisations,

such as universities and specialist colleges. The Australian Government has

several policy levers available to it that impact the workforce, including:

According to the new National

medical workforce strategy 2021–2031 (Medical Strategy), in 2020–21,

the Australian Government spent $1.5 billion on health workforce and training

programs, with an additional $320 million allocated to universities for CSPs in

medicine (p. 12).

Caring for the workforce

The COVID-19 pandemic has

exposed and exacerbated significant vulnerabilities within the health system as

it has highlighted the challenges of caring for its greatest resource, its

workforce. Although this is not a new issue, the pandemic has focused attention

on it due to the unprecedented pressure people working in the health sector are

under and the anticipated long-term effects this may have on individuals and

the system more broadly.

While responsibility for

the workforce often sits with employers under mostly state and territory

legislation, the sheer scale of some problems, such as burnout, and the

potential risks associated with them, means that an interconnected response is

needed across the sector.

Emotional wellbeing,

burnout and COVID-19

Concerns over health

professionals’ wellbeing have been heightened by the COVID-19 pandemic. As

stated in one article,

‘the staffing crisis is self-perpetuating, creating a vicious cycle. The worse

it gets, the more remaining staff are under pressure’.

Several emerging studies

have examined this issue, with the Frontline Healthcare Workers Study- one of the largest Australian surveys conducted so far during the pandemic- finding that

mental health symptoms had become commonplace among frontline workers with:

- 59.8% of participants experiencing mild to

severe anxiety

- 70.9% experiencing moderate to severe

burnout

- 57.3% experiencing mild to severe

depression.

Another study, which surveyed almost 1,000 Victorian health professionals, found 22.5% reported moderate to severe

depression, 14% reported moderate to severe anxiety and 20.4% reported moderate

to severe post-traumatic stress symptoms, with higher rates reported by

paramedics and nurses. In addition, 65.1% of participants reported emotional

exhaustion, which the authors state reflects moderate to severe burnout. Burnout

has been associated with poorer quality care and patient safety and linked to moral distress in Australian frontline health workers during the

pandemic.

These issues have been noted at a

national level, with initiatives introduced to try to address the increased

pressure on health professionals, including:

Despite these measures, concern remains over the sustainability of the healthcare workforce,

the retention of staff and the quality of service delivery possible from an

exhausted and stretched workforce. It is also

worth noting that emotional wellbeing and

burnout is only one component of caring for the workforce, and issues such as

physical safety and moral distress are equally important considerations.

Regulation of the workforce

The National Registration and Accreditation

Scheme (National Scheme) was

established following the passage of the Health Practitioner Regulation National Law (National Law) in each state and territory parliament

and came into effect in 2010. Under the National Law, 15 national boards are responsible

for registering and regulating the 16 health professions that have ‘protected titles’. The professions with protected titles include doctors, nurses, pharmacists and psychologists.

As part of its function, the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (Ahpra) manages registration and renewal for health

practitioners and publishes a register of practitioners.

In February 2022, the Health Ministers Meeting agreed to amend the National Scheme through the

Health Practitioner Regulation National Law Amendment Bill. The Bill was

introduced in May 2022 to the Queensland Parliament, as the host

jurisdiction of the National Law.

Some health professions are ‘self-regulated’ (that is, not regulated under the National Law),

including social workers, speech pathologists and audiologists. For healthcare

workers outside the National Scheme, there is a Code of Conduct for Health Care Workers, which establishes expected standards of care and

allows for investigations into alleged breaches of the code. The implementation

and regulation of the code is a state and territory responsibility.

During the last

Parliament, the Senate Community Affairs References Committee conducted an inquiry into the administration of registration and notifications by Ahpra and related

entities under the National Law. The inquiry made 14 recommendations aimed at not only simplifying and amending the registration process,

but also recommending aged care workers, social workers and personal care

workers be included in the National Scheme (pp. xiii–xiv). This recommendation

reflects the position of the Australian Association of Social Workers, which expressed concern that ‘social worker’ was not

a regulated, protected title (p. 7). The Morrison Government did not respond to

the inquiry prior to the election.

Workforce challenges

The provision of a

sustainable health workforce that provides safe, high-quality care to everyone

who needs it is a continuing challenge, and one experienced worldwide that has been made even more difficult with the unprecedented

demands placed on the system and the workforce by the COVID-19 pandemic. This

section briefly considers some of the ‘wicked problems’ associated with the

system, touching on geographic distribution, medical education and training, and

the complex and evolving health system.

Geographic

(mal)distribution

The majority of health

professionals work in major cities, with the number of practitioners decreasing steadily by remoteness area, despite reports

illustrating that people living outside major cities have increased health risk factors, chronic

conditions and higher mortality rates. As illustrated in Table 1, some health

professions are in very short supply by geography, particularly specialists and

psychologists (noting that issues accessing psychologists have been reported across Australia).

Table 1 Employed

health professionals per 100,000 population, by remoteness area, 2018

|

Major cities |

Inner regional |

Outer regional |

Remote |

Very remote |

| Dentists |

57.4 |

40.6 |

35.5 |

27.1 |

21.1 |

| General practitioners |

105.2 |

108.9 |

103.5 |

136.6 |

152.8 |

| Nurses and midwives |

1,030.2 |

1,004.6 |

970.5 |

1,137.0 |

1,191.3 |

| Occupational

therapists |

57.3 |

48.0 |

44.7 |

32.7 |

19.6 |

| Optometrists |

18.1 |

15.7 |

10.8 |

8.4 |

6.9 |

| Pharmacists |

81.4 |

69.3 |

66.8 |

65.3 |

45.7 |

| Physiotherapists |

94.5 |

65.7 |

52.6 |

44.7 |

50.9 |

| Podiatrists |

16.0 |

16.4 |

10.4 |

10.7 |

6.9 |

| Psychologists |

74.6 |

47.7 |

33.5 |

27.1 |

18.5 |

| Specialists |

143.1 |

82.7 |

62.9 |

60.6 |

22.2 |

Notes:

Calculations are based on the FTE clinical rate and report health practitioners

working in clinical practice using the Estimated Resident Population as at

2019. Numbers represent those employed and working in their registered

profession. See original source for all data notes.

Source: Australian Institute of Health and

Welfare, ‘Rural and remote health’ – Figure 3 data table, 2020.

Accessibility to health

professionals by geography is not a new issue, with several policy levers available

to encourage more people to practise in rural and remote areas. Approaches

currently used by the Australian Government include:

- programs to offer students clinical

placements in rural and remote locations – for example, the Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training program

- postgraduate training programs, such as the Junior Doctor Training Program

- financial incentives for health

professionals – for example, the Workforce Incentive Program

- working with the relevant Colleges and the

Medical Board of Australia to recognise ‘rural generalist medicine’ as a distinct field of general practice

- location restrictions on overseas-trained doctors and medical graduates,

limiting where they may practise to access Medicare benefits

- rules associated with CSPs, such as the Bonded Medical Program (BMP), in which participants need to meet their

return-of-service obligations by working in a Distribution Priority Area (DPA)

‘BMP’ location.

Workforce

classifications

The Department of Health uses

the DPA and District of Workforce Shortage (DWS) as health workforce classifications for medical

practitioners (and general practitioners) and medical specialists, respectively.

In general, a location is classified as DPA or DWS if the community has

insufficient access to doctors. However, some locations automatically qualify

as DPA:

A Senate inquiry into the provision

of primary care in regional locations recommended in its interim report, among other things, that the Department of Health

urgently review the Modified Monash Model (p. xiii).

Medical education and

early postgraduate training

The Australian Government

tightly controls the number of medical CSPs, which are allocated to accredited medical schools through funding agreements. While the Government does not impose a cap on the total number of

medical students enrolled, the cap on medical CSPs does significantly impact

enrolment numbers. This approach to CSP allocation by the minister is currently only applied to medical CSPs.

One of the priorities in

the Medical Strategy is to reform the training pathways. The strategy estimates that a

person invests 10–20 years in their medical education before attaining

specialist registration. This training usually includes a medical degree,

followed by an internship, residency and specialist training to meet the

standards to become a fellow of a specialist medical college. In dollar terms,

the overall cost of this training is approximately $1 million to $2.6 million

(p. 45).

The Medical Deans Australia and New Zealand propose redeveloping the medical training continuum

to deliver a sustainable medical workforce that better meets people’s health

needs, which is the right size, shape and distribution (p. 2). The Medical

Deans state ‘in essence, the current training continuum is not delivering the

doctors our communities need and is hindering our ability to prepare doctors

for their roles in the future’ (p. 7 and see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Current and

proposed outcomes for medical training models

Source:

Medical Deans Australia and New Zealand, Training Tomorrow’s Doctors: All Pulling in the Right

Direction, discussion

paper, September 2021, 7.

Internships and an

increased focus on generalist competencies and skills

The Australian Medical

Council (AMC) is currently working on changes to the medical internship training,

which arose from 2 separate, although somewhat overlapping, reviews.

In 2014, the Council of

Australian Governments (COAG) commissioned an independent review of the

existing model of medical intern training with the aim of considering potential

reforms. The final report was released in October 2015. The Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council accepted most of the recommendations, including that

internships move to a 2-year ‘transition to practice model’ to emphasise

generalist competencies and skills. At the same time, the AMC had commenced a review of the National Framework for Medical Internship. Given the overlap with

the COAG review, the AMC are undertaking activities to respond to both reviews.

The work to date by the AMC on the 2-year framework indicates that people would be eligible for general registration at the end of their first year and specialist training at the end of

their second year. As part of this shift to a 2-year program, the Medical Strategy ‘proposes that specialist medical colleges reduce the length of

training by recognising prior learning where relevant’ (p. 64).

Postgraduate training

bottlenecks

Despite some calls for an increase in CSPs for medical students to better meet rural workforce needs and decrease

dependency on overseas-trained doctors (p. 6), the later stages of the training

system have limited capacity to absorb additional medical graduates. The Australian Medical Students’ Association has stated ‘there is a significant risk that

increasing medical student numbers, without proportional increase of internship

places and speciality training positions, will detrimentally exacerbate the

bottlenecks we have in training doctors…’. Instead, it called on the Morrison Government

to provide adequate funding for the Medical Strategy, with a specific focus on the

proposed data strategy, establishing an advisory body to inform a holistic

approach, as well as creating additional training places in regional areas.

An increase in medical

graduates with limited consideration of postgraduate training places has previously

occurred (p. 7). At the time, the state and territory governments, which are

primarily responsible for the provision of internships, raised concerns that they did not have capacity to offer places to all additional

graduates. In response, the Morrison Government announced the Additional Medical Internship to increase places for Australian-educated international

students, mainly in private hospitals (pp. 176–7). Postgraduate training places

in private hospitals is an element of the Stronger Rural Health Strategy under

the Junior Doctor Training Program.

Complex and evolving

system

Bulk-billing

As Medicare rules and

legislation become increasingly complex, health professionals are at risk of being

unaware of all rules under the scheme. A small study of medical practitioners concluded that doctors are ‘ill-equipped to manage their Medicare

compliance obligations, have low levels of legal literacy and desire education,

clarity and certainty around complex billing standards and rules’ (p. 1). The first

author, Margaret Faux, has suggested that while the (Morrison) Government stated

that 80–90% of patients are bulk-billed, this may only be occurring properly in around 30% of cases due to doctors misunderstanding the bulk-billing rules. Faux also suggested the high bulk-billing rates promoted by the Morrison Government enabled

it to keep Medicare rebates low.

In its General Practice Health of the Nation, the Royal Australian College of General

Practitioners states that the rate of bulk-billing in general practice has been declining for years, though it noted recent artificial

growth due to COVID-19 items. Indexation of Medicare rebates is shown to have

not kept pace with inflation while patient out-of-pocket costs have increased by

almost 50% in a decade (section 3.2).

Digital technology

Realising the

opportunities and overcoming the challenges of using digital technology in the

health system is not an issue unique to Australia. A recent

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) report on empowering the health

workforce noted that digital transformation in the health sector is not merely

about technical change, but requires changes in human attitudes and skills, how

work is organised, and legal and financial frameworks. Digital technologies on

their own cannot transform the health sector, requiring health professionals and

patients to put them to productive use.

Services alongside governments

are investing in digital technologies and with

the release of the National digital health workforce and

education roadmap in 2020,

national work has commenced to

support the existing and future health workforce in developing the skills to

realise the benefits of digital technologies. The roadmap envisages a

technologically confident and capable health workforce, and improved

sustainability of the system, while delivering safe and quality care.

A recent joint report led by Deloitte suggests that many people are willing and ready to use

‘virtual care’ (70% of survey participants) and even more are ready to share

their health data in a digitally enabled health system. The authors estimate

that if the system does not change, then the health workforce will need to be 4

times more productive by 2050 to meet forecast demand (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Current and

anticipated demand on health workers without systemic change

Source:

Baxby et al., Australia’s Health Reimagined (Deloitte, Digital Health Cooperative Research Centre,

Consumers Health Forum of Australia and Curtin University, March 2022), 12.

New and anticipated strategies and plans

The Coalition Government developed

a number of workforce strategies and plans, along with broader plans that

include workforce elements. These include:

The strategies seek to

identify measures for workforce sustainability, health professionals’ wellbeing,

geographic distribution and changing models of care. The focus now shifts to

implementation, which will require commitment, collaboration and ongoing support

and resourcing, and ultimately define the success of these strategies and

plans.

What next?

An effective, sustainable

and accessible health workforce has been a concern for successive governments.

While changes to training and recruitment have been prioritised alongside

high-level workforce strategies, gaps remain. This is particularly the case in

terms of access to health practitioners in regional, rural and remote areas. While

new workforce strategies and frameworks have been welcomed, until they are implemented,

they have little practical impact.

However, it is not only

the pre-pandemic issues that challenge the sustainability of the health

workforce. The last few years have highlighted and heightened issues underpinning

the capacity of Australia’s healthcare system, as well as the incredible

demands placed on health workers. Burnout among health professionals and its implications

is unlikely to be a short-term problem. Addressing this issue will require

resourcing and cooperation across governments and the sector.

Back to Parliamentary Library Briefing Book

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.