Geoff Gilfillan, Statistics and Mapping and Liz Wakerly, Economic Policy

Key issues

While the unemployment rate has fallen over the past five years, underemployment remains high—particularly for young people.

Annual employment growth has been above two per cent for the past 23 months.

Labour force participation continues to grow for women aged 25 years plus.

The casual share of total employees has been stable for the past 15 years.

The state of the labour market

The Australian labour market has been performing relatively strongly in recent years with a falling unemployment rate and strong growth in employment. These outcomes have been achieved in an environment of moderate economic growth.

Despite these positive outcomes, there are signs of continuing excess capacity in the labour market reflected in a persistently high rate of underemployment.

Unemployment and underemployment

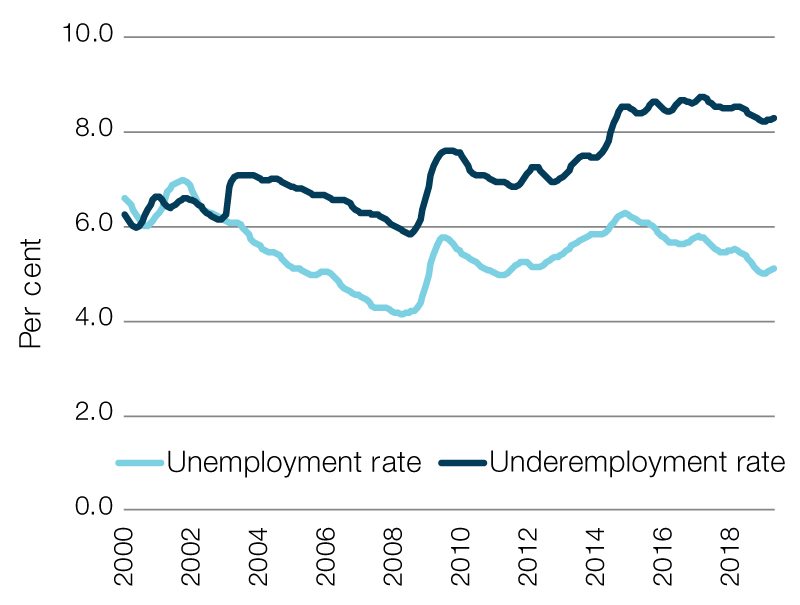

Australian Bureau of Statistics data show the unemployment rate has fallen from 6.3 per cent in December 2014 to 5.1 per cent in April 2019. During the same interval the underemployment rate (or the proportion of the labour force that would prefer more hours of work) has only fallen slightly from 8.5 per cent to 8.3 per cent.

Figure 1: unemployment and underemployment rates, 2000 to 2019

Source: ABS, Labour Force, Australia, cat. no. 6202.0, Table 22, Trend data.

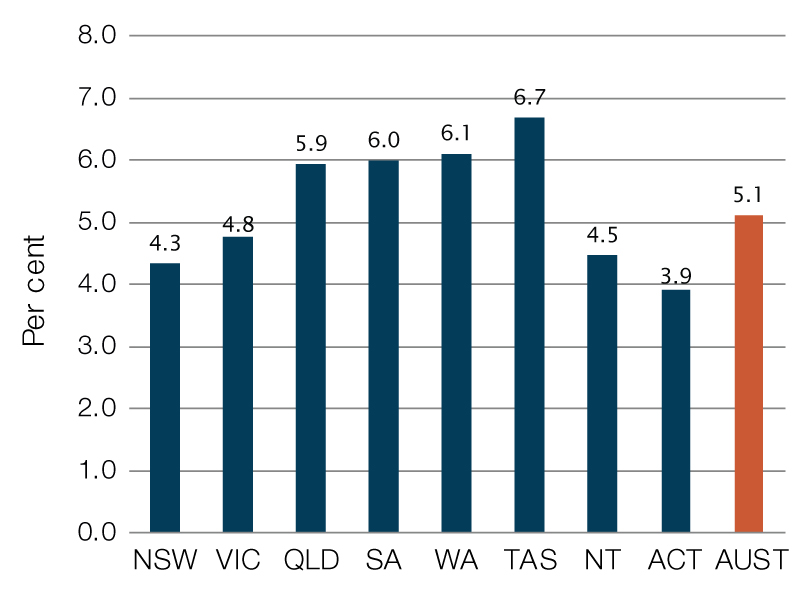

Tasmania and Western Australia had the highest unemployment rates in March 2019, at 6.7 per cent and 6.1 per cent respectively.

The Australian Capital Territory and New South Wales had the lowest unemployment rates in March 2019, at 3.9 per cent and 4.3 per cent respectively.

Figure 2: unemployment rates by state, March 2019

Source: ABS, Labour Force, Australia, cat. no. 6202.0, Tables 1 to 11, Trend data.

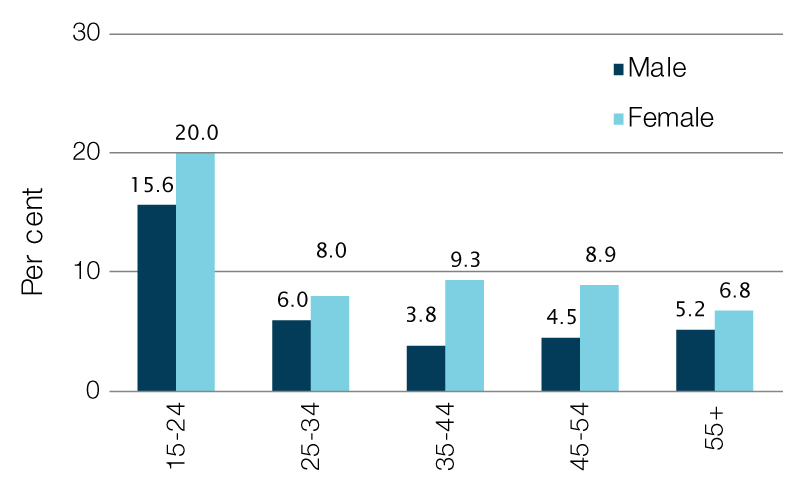

Underemployed people are people that are employed but would prefer additional hours of work. Figure 3 shows the underemployment rate is highest for young males and females aged 15–24 years. Women have consistently higher underemployment rates than men across the age distribution.

A significant proportion of young people are combining part-time hours of work with study commitments while many women are combining part-time work with caring responsibilities. Members of these groups are more likely to be seeking a few additional hours of work per week rather than a full-time job.

Figure 3: underemployment rates by age and sex, March 2019

Source: ABS, Labour Force, Australia, cat. no. 6202.0, Table 22, Trend data.

Youth

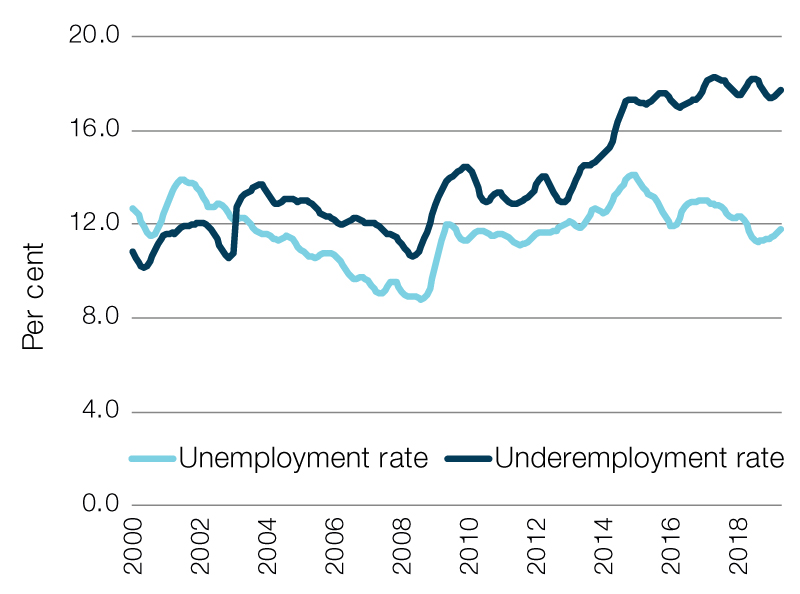

The youth unemployment rate was 11.8 per cent in April 2019—up from 11.4 per cent in January 2019, but down from its most recent peak of 14.1 per cent in December 2014. In contrast, the youth underemployment rate has hovered between 17 and 18 per cent since August 2014.

Figure 4: unemployment and underemployment rates for youth (aged 15–24 years), 2000 to 2019

Source: ABS, Labour Force, Australia, cat. no. 6202.0, Table 22, Trend data.

Table A2.1 of the OECD publication Education at a Glance 2018 shows 11.7 per cent of young Australians aged 18 to 24 years in 2017 were either not employed or not engaged in education or training (NEET). This compares with the OECD average of 14.5 per cent.

Long-term unemployment

ABS data shows levels and rates of long-term unemployment (or people who have been unemployed for 12 months or more) have shown signs of easing slightly in the past 11 months.

The same data source shows the number of people who were long-term unemployed increased from 69,400 in November 2007 to 175,700 in May 2018, but has since fallen to 158,100 in April 2019.

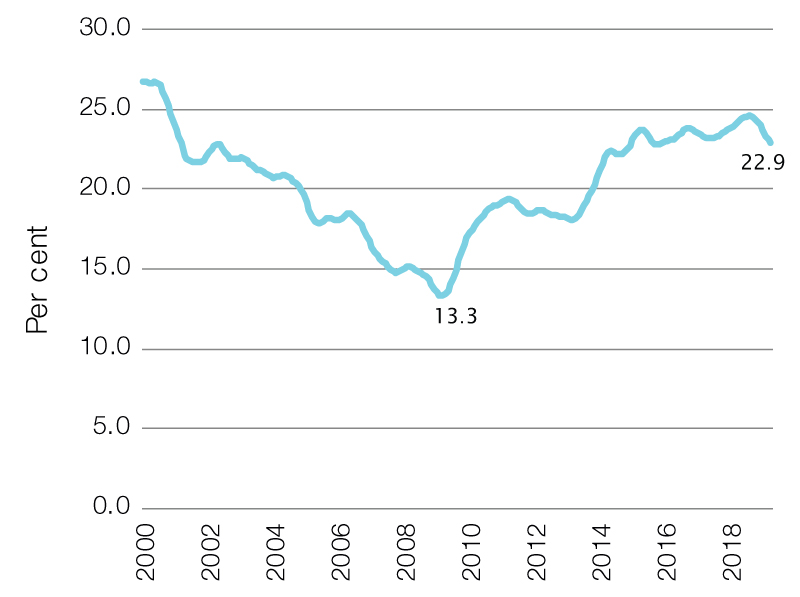

Figure 5 shows around 22.9 per cent of all unemployed people were long-term unemployed in April 2019, compared with 13.3 per cent in March 2009.

Figure 5: prevalence of long-term unemployment, 2000 to 2019

Source: ABS, Labour Force, Australia, cat. no. 6291.0.55.001, Table 14b, Trend data.

Employment growth

ABS data shows annual employment growth stood at 2.5 per cent in April 2019, which compares with the long-run annual average employment growth figure of 1.9 per cent since February 1979.

Employment growth has exceeded two per cent per annum for 23 consecutive months, despite relatively moderate rates of economic growth.

Labour force participation

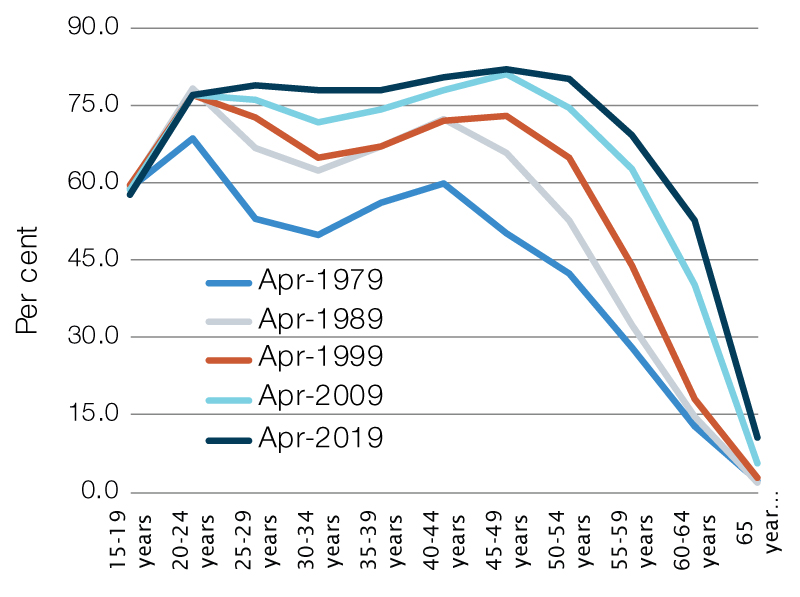

Figure 6 shows labour force participation rates for women have increased substantially for most age groups since March 1979.

Big increases in female participation have occurred across the age distribution for those aged 25 to 60 years. These increases have been facilitated by strong growth in casual and permanent part-time employment; the availability of flexible employment arrangements; and provision of paid and unpaid parental leave.

Figure 6: female labour force participation by age, 1979 to 2019

Source: ABS, Labour Force, Australia, cat. no. 6291.0.55.001, Datacube LM1.

In contrast, labour force participation for men has been much more stable, with small progressive decreases recorded over the past four decades for those aged up to 50 years, but small increases recorded for older age groups over the past two decades.

The decline in participation for men up to the age of 50 years has mainly been driven by injury, ill-health or disability. Higher participation in the older age groups has been driven by higher life expectancy, improved health outcomes for older people and the desire to increase superannuation balances.

Casualisation of the workforce

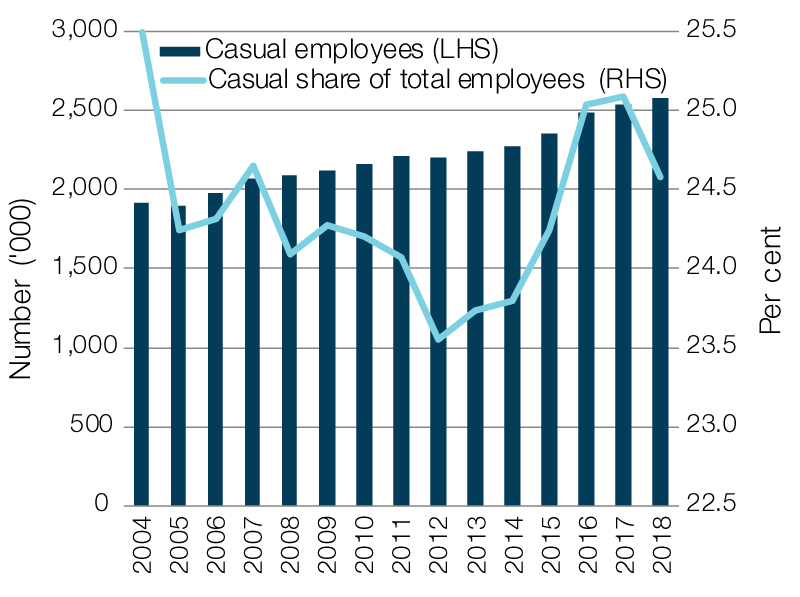

There were 7.9 million employees with paid leave entitlements (or permanent employees) in Australia in August 2018, and 2.6 million employees without paid leave entitlements (or casual employees).

The casual share of total employees has been relatively stable over the past 15 years at close to a quarter of all employees. The casual employee share of total employees fell from 25.5 per cent in August 2004 to 23.5 per cent in August 2012; but has since risen to 24.5 per cent in August 2018.

Between 2004 and 2012, the number of casual employees grew at an annual average of 1.7 per cent and permanent employees grew at an annual average of 3.1 per cent. This trend was reversed between 2012 and 2018 when the number of casual employees grew at an annual average rate of 2.7 per cent compared with an annual rate of growth of 1.8 per cent for permanent employees.

Figure 7: casual employee share of total employees, 2004 to 2018

Source: ABS, Characteristics of Employment, Australia, cat. no. 6333.0, Table 7.3. Note: LHS is left hand side axis and RHS is right hand side axis.

Declining union membership

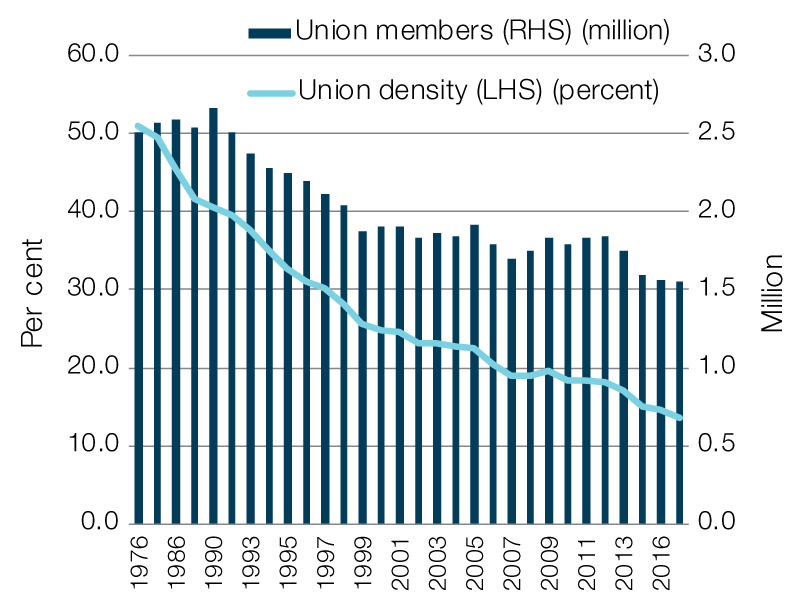

Union membership in Australia has been falling steadily over the past four decades. There were just over 1.5 million union members in 2016, compared with just over 2.5 million in 1976. This represents a decline of around 1 million union members, or 38 per cent.

Union density (the union-member share of total employees) has fallen progressively from 51.0 per cent in 1976 to 24.7 per cent in 2000; and from 18.3 per cent in 2010 to 13.6 per cent in 2018.

Figure 8: union membership and density, 1976 to 2018

Sources: ABS, Trade Union Members, cat. no. 6325.0—1976 to 1993; ABS, Employee Earnings Benefits and Trade Union Membership, cat. no. 6310.0—1994 to 2013; ABS, Characteristics of Employment, Australia, cat. no. 6333.0—2014–2016. Note: LHS is left hand side axis and RHS is right hand side axis.

The shift from employee coverage by enterprise agreements to awards

Awards are legally enforceable determinations made by federal or state industrial tribunals that set the terms of employment (pay and/or conditions), for workers in a particular industry or occupation.

Collective or enterprise agreements set the terms of employment (pay and/or conditions) for a group of employees in an enterprise or organisation. These agreements are usually registered with a federal or state industrial tribunal or authority.

There has been shift in coverage of employees by enterprise agreement to awards in recent years. It is not clear why this shift has occurred or whether it has had some impact on overall wage growth.

ABS data shows the proportion of all employees covered by an award steadily increased from 18.8 per cent in May 2014 to 21.0 per cent in May 2018 (when using a consistent comparable methodology).

The proportion of employees covered by a collective agreement fell from 41.1 per cent to 37.9 per cent over the same period. Around 37.3 per cent of all employees were covered by individual agreements in May 2018, and 3.8 per cent were owner-managers of incorporated enterprises.

During this four-year period, the number of employees covered by awards increased substantially by 374,100 (or 20.1 per cent) to 2,235,000; while the number covered by collective agreements fell marginally by 36,500 (or 0.9 per cent) to 4,037,000.

Workplace relations

Labour hire arrangements

New legislation has been introduced in a number of states in recent years to provide greater protection for labour hire workers.

The labour hire industry is a source of flexible, often short-term employees for a range of different types of businesses. ABS data shows just under 80 per cent of labour hire workers did not have access to leave entitlements (casual employees) in August 2018 and a quarter did not expect to be with their current employer in 12 months. The same data source showed there were around 126,000 people that were paid by an employment agency or labour hire firm in August 2018. The labour-hire employee share of all workers in Australia has hovered around one per cent for the past decade.

The three industries that account for the largest shares of all labour hire workers are Administrative and Support Workers (19.2 per cent), Manufacturing (17.4 per cent), and Public Administration and Safety (10.8 per cent).

Labour hire arrangements are diverse. The typical arrangement is where a labour hire company supplies or on-hires a worker (employee or independent contractor) to perform work for a third party (the host) for an agreed fee. While the worker is under the direction of the host, the employment/contractual relationship is between the worker and the labour hire company which has responsibility for providing the correct pay and conditions to labour hire workers.

Labour hire arrangements become illegal when used to undercut workers’ conditions. Labour hire workers can sometimes miss out on basic rights such as minimum wages, penalties, loadings, overtime allowances, leave and superannuation entitlements. The Report of the Migrant Workers Taskforce 2019 included references to underpayment of wages and non-payment of the Superannuation Guarantee to migrant workers by labour hire companies. Upon the release of the report the Coalition government gave in-principle support to the 22 recommendations which included penalties for wage exploitation.

The Taskforce report found that exploitative labour hire practices can involve sophisticated pyramid structures, multiple sub-contracting arrangements (increasing the risk of non-compliance) and the involvement of related business, such as (substandard) accommodation providers. (See, for example, the Fair Work Ombudsman’s Harvest Trail Inquiry report.)

Both the Coalition and the Australian Labour Party have indicated that they support greater regulation of labour hire arrangements. In the 2019–20 Budget, the Coalition allocated $26.8 million over four years from 2019–20 to establish a National Labour Hire Registration Scheme to ‘protect vulnerable workers, including migrant workers’. The scheme will require the registration of labour hire operators in high-risk sectors such as horticulture, cleaning, meat processing and security. Legislation that regulates the labour hire industry has recently been introduced in Queensland and Victoria. Key regulations include:

- a requirement for labour-hire service providers to hold a licence, with each state having a publicly accessible register of licensed providers

- a requirement for those hosting workers to only use licensed providers

- a requirement for providers to pass ‘a fit and proper person test’ to obtain a licence (and demonstrate financial viability or show compliance with various laws) and

- monitoring of compliance, with substantial penalties for non-compliance.

In 2018 the South Australia Government introduced legislation to repeal the Labour Hire Licensing Act 2017, following ‘feedback raised by stakeholders’ including the South Australian Wine Industry Association (SAWIA).

Conversion to full-time and part-time (permanent) employment

Research undertaken by the Melbourne Institute, using four waves of Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey data, found 40 per cent of casual employees had found non-casual employment within three years. However, some may continue to remain in the non-preferred state of being ‘long-term casuals’.

Casual conversion clauses were inserted into awards to provide a mechanism for employees who were, as a matter of law, permanent employees (but were employed on a casual basis), to seek conversion of their employment from casual to (permanent) full time or part time status. The Fair Work Amendment (Right to Request Casual Conversion) Bill 2019 seeks to extend the effect of a Fair Work Commission decision to include a right to request to convert to full-time or part-time (permanent) employment in 85 modern awards, so that all eligible employees in the national system have access to such a right. The Bill does this by inserting a new right to request casual conversion into the National Employment Standards in the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth).

Of the 122 modern awards, 113 currently contain a casual conversion clause and around two-thirds of existing current enterprise agreements (across all industries) do not have a casual conversion clause.

The conversion clause essentially extends the right for casual employees that have been employed on a long-term systematic basis the right to seek permanent employment. However, employers would be able to refuse requests for conversion if they have reasonable grounds to support that decision.

Further reading

G Gilfillan, Characteristics and use of casual employees in Australia, Research paper series 2017–18, Parliamentary Library, Canberra,

19 January 2018.

G Gilfillan and C McGann, Trends in union membership in Australia, Research paper series 2018–19, Parliamentary Library, Canberra,

18 October 2018.

G Gilfillan, Trends in use of non-standard employment, Research paper series 2018–19, Parliamentary Library, Canberra, 19 December 2018.

G Gilfillan, Developments in the youth labour market since the GFC, Research paper series 2016–17, Parliamentary Library, Canberra,

31 August 2016.

Back to Parliamentary Library Briefing Book

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.