Dr Hunter Laidlaw, Science, Technology, Environment and Resources

Elliott King, Economic Policy

Key issue

Research and development (R&D) in science and technology underpins growth in jobs and productivity. Innovation in these sectors helps to drive human progress.

Australia’s overall level of R&D investment as a proportion of gross domestic product is below the OECD average and has not been increasing.

National Science Statement

Under the 2017 National Science Statement, the Australian Government envisages a society ‘engaged in and enriched by science’. The Statement also recognises science as fundamental to the economy—a concept reinforced by the 2017 Innovation and Science Australia report Australia 2030: Prosperity through Innovation.

The Statement provides the following principles to guide government decision-making and investment:

- science as fundamental to the economy

- ensuring investment in scientific research is focused on high-quality research

- ensuring scientific research support is stable and predictable

- encouraging collaboration across scientific disciplines and sectors (domestic and international) and

- maximising the opportunities for Australians to engage with the science process.

The recent agenda

Developed in 2015, the National Innovation and Science Agenda focussed on science, research and innovation as long-term drivers of jobs, economic growth and prosperity. Over $1.1 billion was committed to 24 measures from 2015–16 to 2018–19 focussing on the four main pillars of the agenda:

- culture and capital: embracing risk, making more of public research and opening up new sources of finance

- increasing collaboration between industry and research

- talent and skills: developing world-class talent for future jobs and

- government leading by example to embrace innovation and agility in the way it does business.

Impact of technological developments

Advances in technology are influencing the direction of the Australian economy and will affect jobs and society into the future. These changes are likely to cut across all sectors of the economy, including digital systems (such as artificial intelligence and machine learning—see the ‘Digital World’ chapter elsewhere in this publication), telecommunications (5G), improved battery technology, health, transport and agriculture.

Parliament faces the challenge of being prepared for these developments and the changes they will bring—not just from domestic activities but also at the international level. This involves ensuring that the existing regulatory frameworks across a vast array of scientific and technological fields, and the sectors affected by these developments, are fit-for-purpose and provide the suitable protections and controls expected by society.

5G and the Internet of Things (IoT)

Fifth generation (5G) mobile technology is expected to provide a very fast network that will eventually approach 10 gigabits per second (100 times faster than the fastest NBN plans currently available). These speeds greatly increase the data capacity that the network can handle, so this technology may enable the development of more integrated networks such as an Internet of Things (IoT).

An IoT can enable otherwise independent ‘things’ (such as devices, appliances or vehicles) to interact through a network. This could be used to optimise their interactions with each other and their environment (such as with other traffic and the road network).

CSIRO has been conducting analyses of long-term trends in technology and what effect these may have on industries and on Australia in the future. These ‘roadmaps’ from 2018 include:

- Cyber Security, particularly in relation to sectors identified by the government as areas of strategic priority and competitive strength

- Space, including the use of space-derived data and services, tracking space objects, and developing technology for space exploration and utilisation

- Hydrogen, to develop a hydrogen industry in Australia for use in transport, heating and electricity, as well as for export.

A series of Horizon Scanning reports has also been commissioned through Australia’s Chief Scientist. The recent focus of these analyses is on synthetic biology, artificial intelligence and the Internet of Things (IoT).

R&D incentives

How R&D is supported varies considerably between countries, with most OECD countries employing a combination of both direct and indirect support measures.

Direct support is directly attributable to government funding and can take the form of grants and the purchase of R&D services. Indirect support often comes through the tax system in the form of tax incentives and preferential treatment of R&D outputs (such as generous patent laws).

Government funded R&D in Australia

In Australia, the largest component of government-funded support for R&D is provided through the R&D Tax Incentive (R&DTI). This is the main instrument used to support business R&D, and equated to roughly $2.24 billion in the 2019–20 Budget.

The R&DTI provides tax offsets to incorporated companies for R&D activity. According to the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science:

Eligible companies with a turnover of less than $20 million [may] receive a refundable tax offset, allowing the benefit to be paid as a cash refund if they are in a tax loss position.

Companies with a turnover of over $20 million receive a non-refundable tax offset to reduce the tax they pay.

Research Block Grants (RBGs) account for about 20 per cent of R&D support (about $1.9 billion in the 2019–20 Budget) and are provided to the higher education sector. RBGs are not specific project funding. Instead, they are used to cover the indirect costs of research (such as overheads, facilities and equipment) and research training.

A range of competitive direct grants are also supported—these are typically provided to eligible applicants on the basis of merit and a peer-review process. This includes grants administered through the Australian Research Council (ARC) and National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Medical and health research is also supported through the Medical Research Future Fund. Cooperative Research Centres (CRCs) and rural R&D corporations also receive significant funding.

Government support levels

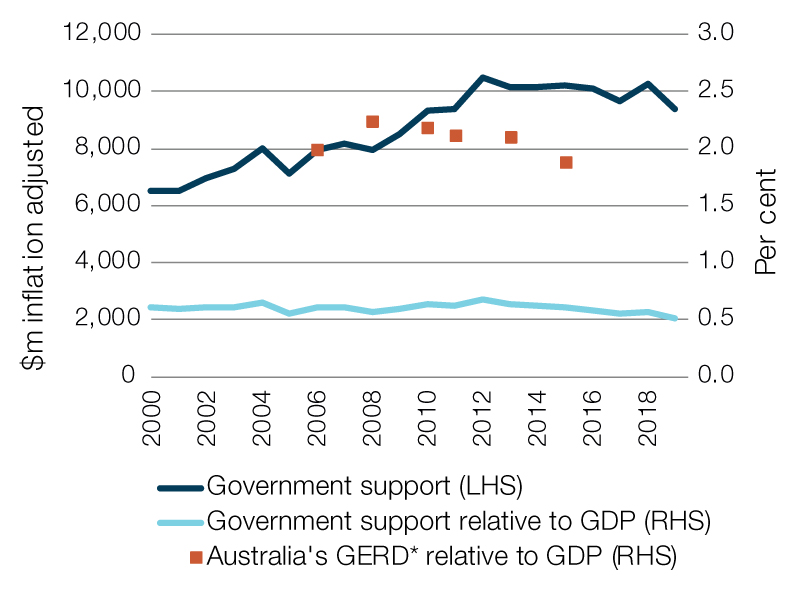

In real terms, total government investment in R&D has remained relatively stable for several years (see Figure). This total investment does include support in areas other than science and technology, such as through the ARC, although most ARC support is provided to scientific fields.

As a proportion of GDP, government investment in 2018–19 is estimated to be 0.51 per cent. This is below the long-term average of 0.62 per cent and is the lowest level in 40 years.

Figure: R&D support in Australia

*GERD: Gross Expenditure on R&D.

Source: Department of Industry, Innovation and Science, 2018–19 Science, Research and Innovation Budget Tables, 2018 and Australian Bureau of Statistics, Research and Experimental Development, Businesses, Australia, 2015–16, cat. No. 8104.0, Canberra, 2017.

Overall R&D funding trends

The trend in government investment is consistent with the trend in Australia’s gross expenditure on R&D (GERD) which, as well as the government support discussed above, includes spending by business, higher education and private non-profit sectors. The latest available data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics places this at 1.88 per cent of GDP in 2015–16, having declined from a high of 2.25 per cent in 2008–09.

This proportion is below the OECD average, which was 2.38 per cent in 2015–16. Several countries exceed 3 per cent. There is a general trend of overall steady growth in the average R&D funding across OECD countries in the last decade.

Australia does not have a set target for R&D investment as a proportion of GDP. A recommendation to spend 3 per cent of GDP on R&D from a 2015 Senate Economics References Committee into Australia’s innovation system was rejected by the government.

Australia’s performance

Governments worldwide implement a variety of measures to support and promote R&D and some have set GDP targets. The high degree of variance in policies across countries imposes some challenges in assessing the effectiveness of policies. Australia ranked twentieth in the 2018 Global Innovation Index: placing eleventh on ‘input’ measures and thirty-first on ‘output’ measures.

As noted in a 2017 OECD Economic Survey,Australia’s transfer of publicly funded research into commercial outcomes is relatively poor. Out of a selection of 26 OECD countries, Australia ranked last with respect to the proportion of businesses collaborating with the higher education sector or public sector research agencies.

The OECD identified the low level of university and company engagement as a barrier to improving commercial outcomes. It also noted that despite rapid uptake of the R&DTI following its implementation in 2011, its effectiveness at increasing R&D activity has not matched the level of investment.

Similar findings were made in the 2016 Review of the R&D Tax Incentive. Notably, the review panel found that the program ‘falls short of meeting its stated objectives’ in producing additional R&D and inducing greater exchange of ideas among firms, and between firms and public research institutions.

These observations apply not just to the R&DTI but to innovation policy more widely. It is not generally possible, on the available evidence, to state unambiguously the effectiveness of R&D incentives without consideration of the broader regulatory and business environment.

The OECD has recommended more rigorous programme evaluations of R&D investment, with the Productivity Commission and the Australian National Audit Office echoing this sentiment. Additionally, the OECD suggests that there is a case for rebalancing the policy mix between indirect and direct support.

Other proposed reforms

A Senate inquiry into Australian Government Funding Arrangements for non-NHMRC Research reported in October 2018. The committee made 15 recommendations, including in relation to the administration of funding and for the government to provide greater coordination of Australia’s research investment.

Other recommendations were for consideration to be given to a ‘future or translation fund’ for non-medical research as well as increased involvement in international research funds such as

Horizon Europe (the EU’s proposed €100 billion research and innovation program for 2021–2027 that will succeed the

Horizon 2020 program).

Further reading

CSIRO, ‘CSIRO Futures reports’, CSIRO website.

Productivity Commission, An Overview of Innovation Policy, Shifting the Dial: 5 Year Productivity Review, Supporting Paper No. 12, Canberra, 2017.

H Ferguson,

University research funding: a quick guide, Parliamentary Library, Canberra, 2019.

Back to Parliamentary Library Briefing Book

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.