Emma Knezevic and Bill McCormick, Science,

Technology, Environment and Resources

Key Issue

Threats to the Great Barrier Reef from poor water quality and climate change urgently need to be addressed to maintain its natural values and ensure long term sustainable uses of the park.

The Great Barrier Reef (GBR) extends 2,300km along

the coast of Queensland (see Figure 1) and is the world’s largest system of

coral reefs. With great diversity of species and habitats, the GBR is one of

the richest and most complex natural ecosystems on earth. It was inscribed on the

World Heritage List in 1981. The

reef is visited by more than two million people each year and the catchment

region generates

a value-added economic contribution of $5.7 billion annually.

Managing and conserving the GBR and its unique

values is a challenge, and both the Australian and Queensland Governments have

specific responsibilities.

The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority

(GBRMPA), a Commonwealth authority, manages

the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, as established by the Great Barrier Reef

Marine Park Act 1975 (Cth). GBRMPA’s regulatory tools include zoning, plans

of management, permits

and policies.

The Queensland Government, through the Queensland

Parks and Wildlife Service and Fisheries Queensland, works with the

Commonwealth in managing adjacent state marine parks and islands.

Successive state and Commonwealth governments have

referred to the GBR as the ‘best

managed reef in the world’. They highlight GBRMPA’s multiple-use approach

to balancing

fishing, tourism and recreation, as well as maritime and transport access.

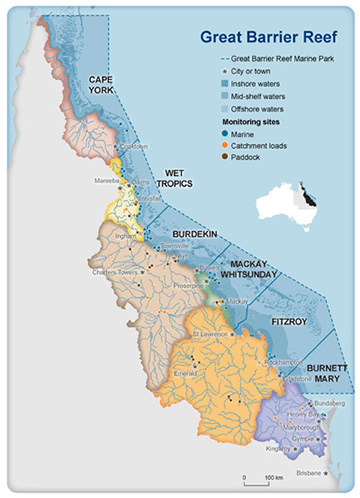

Figure 1: Great Barrier Reef and adjacent

catchments

Source:

Reef Plan Report Card Summary

Threats to the GBR

Threats to reef health include coral bleaching due

to elevated sea temperatures, ocean

acidification, outbreaks of Crown of Thorns Starfish (COTS), and cyclones. Threats

also arise from coastal development, agriculture and industrial activities on adjacent

land and the associated catchment

run-off from these activities. As such, land and water management within or

adjacent to the GBR contributes to cumulative impacts on the

reef ecosystem.

A 2012 study,

published by the National Academy of Sciences (NAS), found that coral cover had

declined by around 50% since 1985. Tropical cyclones, predation by COTS and

coral bleaching accounted for 48%, 42% and 10% of the estimated loss,

respectively. The authors concluded that tropical cyclones and coral bleaching

can be linked to climate

change and mitigation measures are unlikely to be effective in the short

term.

Water quality and reef management

In 2003, the Queensland and Australian Governments

released the Reef Water

Quality Protection Plan (Reef Plan) to address the issues of run-off from

land. This plan was updated

in 2009 and 2013.

Funding to implement the plan was sourced from the

Natural Heritage Trust, Caring for our Country and Reef Rescue programs. The

Reef Plan website states

that, in 2013, the Australian and Queensland Governments collectively allocated

$375 million over five years to its implementation. In 2015 a further $100

million was committed by each government.

The GBR

Outlook Report 2014, prepared by GBRMPA, explains that run-off into the GBR

from adjacent land carries increased nutrients found in fertilisers such as

nitrogen and phosphorus, as well as pesticides and herbicides used in

agriculture. Water quality is further reduced by sediments.

The impact of run-off is uneven across the GBR, and

depends on pollutants and their concentrations, catchment sources and distance

of reefs from the coast. Similarly, the effects of coral

bleaching and COTS

outbreaks vary by location and timing. The 2012 NAS study (above) reported

that the remote northern region had relatively low

mortality from COTS and cyclones, and coral cover was stable with the exception

of a slight decline due to bleaching from 1998 to 2003.

In contrast, a 2016 bleaching event has most severely impacted the northern

region.

Crown-of-Thorns Starfish (COTS)

Occasional COTS outbreaks are considered natural,

but outbreak frequency and intensity have

increased as a result of reduced water quality. In particular, increased

nutrient levels as a result of catchment run-off encourage plankton blooms, increasing

the food available to COTS larvae. During COTS outbreaks, the starfish eat

coral faster than it can re-grow, leading to a decline in coral cover.

In addition to intensive efforts to manually

control COTS during outbreaks, improving the water quality is expected to reduce

the likelihood of COTS outbreaks.

Coral bleaching

Coral

bleaching is caused by heat stress when water temperatures rise for

prolonged periods. Coral bleaching is the term used when tiny marine algae that

live in coral (zooxanthellae) are expelled. The coral tissue then appears

transparent, revealing the white skeleton.

Significant coral bleaching outbreaks occurred on

the GBR in 1998 and 2002. However,

2016 has seen the most extensive bleaching event with reports of up to 90% of

some reefs affected to some degree. Impacts from this event are still

unfolding, but coral mortality (at June 2016) is 22% across the GBR,

with the most affected sites observed in the northern section. The Australian

Institute for Marine Science explains:

Between February and May, the GBR experienced

record warm sea surface temperatures. Extensive field surveys and aerial

surveys found bleaching was the most widespread and

severe in the Far Northern management area, between Cape York and

Port Douglas. Here, bleaching intensity was ‘Severe’ (more than 60% community

bleaching). Bleaching intensity decreased along a southerly gradient. While

most reefs exhibited some degree of bleaching, this bleaching varied in

intensity (from less than 10% to over 90% community bleaching) and was patchy

throughout most of the management area. (View the GBRMPA map for more information.)

World Heritage in danger?

Since 2005, the World Heritage Committee has

repeatedly warned Australia that the GBR was under consideration for inclusion

on the List of World Heritage In Danger.

‘In danger’ listings are designed to:

...inform the international community of

conditions which threaten the very characteristics for which a property was

inscribed on the World Heritage List, and to encourage corrective action.

The World Heritage Committee’s decisions relating to

the GBR in recent years have raised concerns about proposed and existing

developments in and near the World Heritage Area, water quality issues

(including sediment and agricultural nutrient run-off), and climate change.

The Australian and Queensland governments have responded

to these concerns in a number of ways, to ensure the GBR is not placed on the

‘in Danger’ list. A key part of this response is the Reef

2050 Long-Term Sustainability Plan, which was informed by a strategic

assessment of the impacts on the reef. This Plan aims to put in place a

long-term, comprehensive approach to improve the condition of the GBR. The Implementation

Strategy identifies priority actions in the implementation of the Reef 2050

Plan.

Controversy arose in May 2016 when the Australian

Government’s Department of the Environment successfully requested the removal

of references to Australian sites, including the GBR, in a United Nations report,

World

Heritage and Tourism in a Changing Climate. The Department was reportedly

seeking to avoid confusion over terminology.

Proposed Reef Fund

The Coalition’s 2016 Election policy

proposes the creation of a $1 billion Reef Fund to finance clean energy projects

in the GBR catchment region. The Clean Energy Finance

Corporation will manage the Fund. It is unclear how the Reef Fund will directly

benefit the health of the GBR in the short to medium term. It will not fund

projects primarily designed to improve water quality, although improvements to

water quality may arise as a secondary benefit from some of the clean energy

projects.

The policy cites examples of projects that will be

funded such as:

- solar panels to substitute for diesel on a farm and

- more energy efficient pesticide sprayers

and fertiliser application systems.

Further reading

GBRMPA, Great Barrier Reef Outlook Report 2014, 2014

Australian and Queensland Governments, Reef 2050 Long-term Sustainability Plan, 2015

Back to Parliamentary Library Briefing Book

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.