What is parliamentary privilege?

The term parliamentary privilege refers to special legal rights and immunities which apply to each House of the Parliament, its committees and members. These provisions are part of the law of the Commonwealth. This infosheet deals with the subject from the perspective of the House of Representatives, but the major details also apply to the Senate.

Why is it necessary?

The Houses of the Commonwealth Parliament, in common with other parliaments, are given a special legal status because it is recognised that the tasks they have to perform require additional powers and protections. Special rights and immunities are necessary because of the functions of the House; for example, the need to be able to debate matters of importance freely, to discuss grievances and to conduct investigations effectively without interference.

Main features of the law and practice

Section 49 of the Australian Constitution provides that, until declared by the Parliament, the powers, privileges and immunities of the Senate and the House of Representatives and the members and committees of each House shall be those of the British House of Commons at the time of Federation (1901). It was not until 1987, and following a thorough review of the whole subject by a joint select committee, that the Commonwealth Parliament passed comprehensive legislation in this area.

The main features of the arrangements in the Commonwealth Parliament are as follows:

- each House, its committees and members enjoy certain rights and immunities (exemptions from the ordinary law), such as the ability to speak freely in parliament without fear of prosecution (known as the privilege of freedom of speech)

- each House has the power to deal with offences—contempts—which interfere with its functioning

- each House has the power to reprimand, imprison or impose fines for offences

- complaints are dealt with internally (within parliament)—they may be considered by the Committee of Privileges and Members’ Interests which will report to the House which may then act on the matter in light of the committee’s report

- there is a limited ability for decisions of the House to imprison people to be reviewed in court

- the Parliamentary Privileges Act 1987 creates a special category of criminal offence in order to strengthen the protection available to witnesses who give evidence to parliamentary committees.

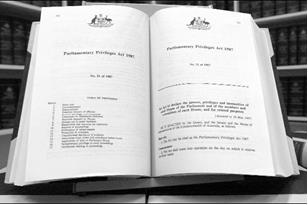

Parliamentary Privileges Act

The privilege of freedom of speech

The privilege of freedom of speech is often described as the most important of all privileges. Its origins date from the British Bill of Rights of 1689. Article 9 of the Bill of Rights provides:

That the freedom of speech and debates or proceedings in Parliament ought not to be impeached or questioned in any court or place out of Parliament.

As this was one of the privileges of the House of Commons in 1901, it was inherited by the House and the Senate under the terms of the Australian Constitution. Section 16 of the Parliamentary Privileges Act preserves the application of the traditional expression of this privilege, but spells out in some detail just what may be covered by the term ‘proceedings in Parliament’.

The practical effect of this is that those taking part in proceedings in parliament enjoy absolute privilege. It is well known that members may not be sued if they make defamatory statements when taking part in debates in the House; however, privilege has a broader scope than that. For instance, privilege protects members from being prosecuted if in a debate they make a statement that would otherwise be a criminal offence; for example, a member who felt it necessary to reveal a matter which was covered by a secrecy provision in a law such as personal tax information.

The privilege of freedom of speech has been described as a ‘privilege of necessity’. It enables members to raise in the House matters they would not otherwise be able to bring forward (at least not without fear of the legal consequences). The privilege is thus a very great one, and it is recognised that it carries with it a corresponding obligation that it should always be used responsibly. Pressure from other members, the public and the media would be brought to bear on members who made accusations unfairly in the Parliament. There is also a procedure for individuals who have been offended by remarks made about them in the House to seek to have a response published. Infosheet No. 17 Citizens’ right of reply provides details on this process.

The privilege of freedom of speech is not limited to members of parliament; it also applies to others taking part in ‘proceedings in parliament’. The most obvious example of others who may enjoy absolute privilege are witnesses who give evidence to committees. It is important to note that the privilege only applies to evidence given to properly constituted parliamentary committees, and does not, for instance, apply to party committees.

There is a difference between qualified and absolute privilege. Qualified privilege exists where a person is not liable for an action for defamation if certain conditions are fulfilled; for example, if a statement is not made with malice. Newspapers which report debates in parliament rely on qualified privilege. Absolute privilege, on the other hand, exists where no action may be taken at all, even if, for example, a statement is made with malice.

As well as proceedings in parliament being absolutely privileged, the House, and properly constituted committees, may confer absolute privilege on various papers by authorising their publication. Parliamentary committees often use this power to authorise the publication of submissions and transcripts of evidence given to inquiries. The Parliamentary Papers Act 1908 also extends absolute privilege to the Hansard record of proceedings. The Parliamentary Proceedings Broadcasting Act 1946 does the same in relation to the official broadcast, but absolute privilege does not apply to the broadcast of excerpts of proceedings.

Other privileges

Members may not be required to attend courts or tribunals as witnesses or be arrested or detained in civil matters on sitting days and for five days before and after sitting days. Such immunities also apply when a member of parliament is a member of a committee that is meeting. People required to attend as witnesses before committees may not be required to appear as witnesses before a court or tribunal or be arrested or detained for a civil matter on days they are required to give evidence to the committee. Members and some parliamentary staff are also exempt from jury service. These immunities are justified on the ground that the first duty of members, and others involved, is to parliament and that this overrides other obligations. The immunity from civil arrest and detention does not exempt members from the action of the law—members still must fulfill their legal obligations at a time when parliament is not meeting, and no immunity applies at all in criminal matters.

The ability to deal with offences (contempts)

As well as dealing with people or organisations breaching particular rights or immunities, the House may also take action over matters which, while they do not breach any particular legal power or immunity, obstruct or impede the House in the performance of its functions or members or officers in the discharge of their duties. This is known as the ability to punish for contempt and is similar to the courts’ power to punish for contempt of court.

This power gives the House a flexibility to protect itself and its members against new or unusual threats. Matters can be dealt with under this authority even if there is no precedent for them. A safeguard against misuse of this considerable power is given by section 4 of the Parliamentary Privileges Act which states that conduct does not constitute an offence unless it amounts, or is intended or likely to amount, to an improper interference with the free exercise by a House or a committee of its authority or functions, or with the free performance by a member of their duties as a member. Speakers have also referred to the importance of restraint in the use of the House’s powers to deal with contempts. In addition, the Act prevents action being taken in cases where the only offence was that words or actions were defamatory or critical of the House or a committee or a member. This removed a category under which many complaints had been raised over the years, for example, newspaper reports criticising the behaviour of members.

One of the most important effects of the power to punish contempts is that the House may protect its committees and their witnesses. Committees usually have substantial powers to help them to obtain evidence and information, but they do not themselves have power to take action against any person or organisation who is obstructing or hindering them. If it is misled or obstructed, or if its witnesses are punished or intimidated, a committee may bring the matter to the attention of the House which ultimately may punish for contempt.

The raising of complaints

Complaints of breach of privilege or contempt may only be raised formally by members—a person who believes that there has been an offence must ask a member to raise it in the House. The normal course is for a member to seek the call ‘on a matter of privilege’ and to immediately outline the complaint briefly. The Speaker then considers the matter privately. If satisfied that it has been raised at the first available opportunity and that there is some substance in it (the technical term being that a prima facie case exists) the Speaker may give precedence to a motion on the matter. Usually such a motion would be that the issue be referred to the Committee of Privileges and Members’ Interests, although other motions could be proposed, or a member might advise the House that they did not wish to pursue the matter further. Whether or not a matter is sent to the Committee of Privileges and Members’ Interests for investigation is thus for the House itself to decide.

Committee of Privileges and Members’ Interests

The House has had a Committee of Privileges since 1944. The title was changed to the Committee of Privileges and Members’ Interests in February 2008 (when two committees were combined). Currently the committee consists of 13 members and, like other committees, government members form a majority, although it is traditional that matters of privilege are not considered on a party basis. The committee has the power to call for witnesses to attend and for documents to be produced; that is, it can compel the production of material and the attendance of witnesses. Witnesses, including members, may be asked to make an oath or affirmation before giving evidence.

Traditionally, the committee has met in private. Major changes in procedure were made during an inquiry in 1986–87 relating to the unauthorised disclosure of material relating to a joint select committee. During that inquiry, for the first time, evidence was taken in public and witnesses were permitted to be assisted by legal counsel or advisers. In December 2000 the House agreed to a motion authorising the publication of all evidence or documents taken in camera or submitted on a confidential basis and which have been in the custody of the Committee of Privileges for at least 30 years. These records are now made available through the National Archives of Australia.

The committee itself cannot impose penalties. Its role is to investigate and advise. In its report to the House the committee usually makes a finding as to whether a breach of privilege or contempt has been committed, and it usually recommends to the House what action, if any, should be taken.

As well as investigating specific complaints of breach of privilege, the committee is also able to consider any general privilege issues referred to it by the House. For example, it has conducted an inquiry into whether members’ office records attracted privileged status. It also considers applications for a ‘right of reply’ from people who have been criticised in the House. Infosheet No. 17 Citizens’ right of reply gives details of this procedure.

Consideration by the House

Normally, when a report from the committee is presented, and especially if there is the possibility of further action, the practice is for the House to consider the report at a future time so that members may study the report and the issues before making decisions on it. The House is not bound to follow the committee’s recommendations, and any motion moved is able to be amended.

Penalty options

It has long been recognised that the House has the power to imprison people, but there has been considerable uncertainty as to whether it had the power to impose fines because of doubt as to whether the House of Commons itself had this power in 1901. These doubts were removed by the Parliamentary Privileges Act. Under the Act the House may impose a penalty of imprisonment not exceeding six months on a person, or a fine not exceeding $5,000, or not exceeding $25,000 in the case of a corporation. Neither the House of Representatives nor the Senate has ever imposed a fine under this provision.

Under section 9 of the Act, if the House imposes a penalty of imprisonment, the resolution imposing the penalty and the warrant must set out particulars of the offence. The effect of this is that a court could be asked to determine whether the ground for the imprisonment was sufficient in law to amount to a contempt.

On only one occasion has the House imposed penalties of imprisonment. This was in 1955 when Mr R. E. Fitzpatrick and Mr F. C. Browne were found guilty of a serious breach of privilege by publishing articles intended to influence and intimidate a member in his conduct in the House. They were each imprisoned for three months.

The House’s authority is symbolised by the Mace

For more information

Parliamentary Privileges Act 1987 (Act No. 21 of 1987).

House of Representatives Practice, 7th edn, Department of the House of Representatives, Canberra, 2018, pp. 733–80 and appendix 25 for a full list of matters of privilege raised in the House.

Joint Select Committee on Parliamentary Privilege, Final Report, October 1984. Parliamentary Paper 219 of 1984.

House of Representatives Standing Committee of Privileges and Members’ Interests webpage: www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/House/Privileges_and_Members_Interests

About the House website: www.aph.gov.au/athnews.

X: @AboutTheHouse | Bluesky: @aboutthehouse.bsky.social |

Facebook: Aboutthehouseau | Instagram: @abouttheHouse

Images courtesy of AUSPIC.