17 NOVEMBER 2023

PDF Version [1.02MB]

James Haughton and Sally McNicol

Social Policy

Executive summary

This Quick Guide provides a short

overview of all Australian Government Indigenous-specific bodies; the number of

public servants they employ; their functions and funding; and an overview of

total Australian Government Indigenous-specific expenditure.

There are currently 14 Indigenous-specific bodies at the Commonwealth

level, of which the National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA) is the

largest, plus 4 statutory office holders. Of the 14 bodies, 13 are part of the

Prime Minister and Cabinet portfolio. There are also 5 statutory Indigenous-specific

boards or committees, 5 non-Indigenous-specific statutory bodies which have statutory

Indigenous members, and several non-statutory advisory bodies.

In 2023–24, the Indigenous-specific bodies will employ

2,714 full-time-equivalent public servants. This is 1.41% of the Australian

Government’s 191,861 full-time-equivalent non-military public servants. Some bodies

have employees who are not public servants; these are listed if available.

In 2023–24, these bodies have been allocated approximately

$2.4 billion in budget appropriations and equity contributions, plus $346.6

million from dedicated special accounts (the Aboriginals Benefit Account and

the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Land and Sea Future Fund). They will

also generate an estimated $302.9 million in external revenue.

These bodies represent approximately half of the

Australian Government’s Indigenous-specific expenditure. The other major

components are Indigenous-specific health programs, ABSTUDY, smaller programs

run by other departments, and National Partnerships with states and territories.

All Australian government bodies are subject to the Public

Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) and to auditing

by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO).

Estimated 2023–24 total Australian Government expenditure

on all Indigenous-specific programs is $5.3 billion. This is 0.77% of the

Australian Government’s $684.1 billion budget.

The Australian

Bureau of Statistics estimates that there are approximately 983,700

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, representing 3.8% of the total

Australian population.

Contents

Executive summary

Indigenous-specific Australian

Government bodies

Other government entities

Staffing overview

Body functions, budgets and staff

Prime Minister and Cabinet portfolio

bodies

Attorney-General’s portfolio bodies

Department of Health and Aged Care

bodies

Department of Climate Change, Energy,

the Environment and Water

Other departments, their bodies and

expenditure

National Partnership expenditure<

Australian Government

Indigenous-specific expenditure overview<

Caveat

After 2015–16, most government departments ceased reporting

their total Australian Government Indigenous Expenditure. Expenditure from

several smaller programs can only be estimated.

A range of funding arrangements apply to some Indigenous-specific

bodies. For example:

- Some

bodies are funded by dedicated special

accounts, or by the investment earnings of dedicated special accounts,

rather than budget appropriations. As the special accounts are

government-owned, this is also ‘government funding’, but not from consolidated

revenue.

- Government

departments may pay some bodies additional specific-purpose grants, or funding

for performing contracted services, above and beyond budget appropriations. In

this case, the funding was appropriated to the contracting/granting department,

so appears in the budget of that department. This is usually the National

Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA), but not always. For example, the

Department of Climate Change, the Environment, Energy and Water (DCCEEW) may

pay some Indigenous organisations, such as Ranger groups and Indigenous Protected

Areas management groups, to deliver environmental services (such as feral

animal control), and pays

rent on some national parks (p. 11) to Traditional Owners. Such payments

are considered ‘external revenue’ by the receiving organisation as they are fee

for service income, not budget appropriations.

- Many

bodies also receive income from investments, commercial activities or user

charges. As they are government organisations, this self-generated funding might

also be considered ‘government funding’, but it is not sourced from

consolidated revenue.

- Some

bodies provide financial and staffing details through their own annual reports.

As most annual reports for the 2022–23 financial year have not yet been issued,

the most recent information may be for 2021–22 or earlier years. As the 2022–23

financial year saw a

significant expansion of Indigenous-specific programs and funding, this

information may be out of date.

This guide does not itemise Indigenous-specific

non-government organisations (NGOs) which receive funding from the Australian

Government, for example Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Services

(ATSILS), Native Title Representative Bodies/Service Providers (NTRB/SPs), Registered

Native Title Body Corporates (RNTBCs), and Aboriginal Community Controlled

Health Organisations (ACCHOs). Australian Government support for these

organisations is delivered through grants,

which are included in the budgets listed below of the NIAA, the Department of

Health and Aged Care (DHAC), or other granting departments. Most such NGOs are

regulated by the Office of the Regulator of Indigenous Corporations (ORIC).

Indigenous-specific

Australian Government bodies

This section provides a list, with links, to all Indigenous-specific

Australian Government bodies. Details of the functions, budget and staffing of

each body are given in the next section.

Bodies are listed according to their classification under

the Public

Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), to

which all corporations and entities are subject for reporting and

accountability purposes.[1]

Most are part of the Prime Minister and Cabinet portfolio (PM&C).

Non-corporate Commonwealth entities, PM&C

The NIAA is administratively responsible for 3 statutory

office bearers:

Corporate Commonwealth entities, PM&C

Commonwealth companies, PM&C

Bodies and

office bearers in Attorney-General’s portfolio

Other government

entities

Statutory committees

and boards

These committees advise on or manage some

Indigenous-specific or Indigenous-related issues under a particular Act, and

usually have a majority of Indigenous members.

Statutory members

of non-Indigenous-specific statutory bodies

These bodies have both general and Indigenous-specific

functions, so are required by legislation to have one or more Indigenous

members with relevant expertise, or members with expertise in Indigenous

matters.

Non-statutory

advisory bodies

These advisory bodies provide advice to a minister,

department or other body on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander matters

within their field. As they are not statutory bodies, their existence,

functions and membership are determined as required by the relevant minister.

Membership of such bodies is usually part-time and voluntary, although members

may receive sitting fees, or per diems for travel and accommodation when

performing work for the body. As such bodies are liable to change at short

notice and do not administer legislation or funding, this paper does not go

into detail on their functions or composition. This list may not be exhaustive.

Staffing overview

In Table 1 below, available public servant staffing numbers

for Australian Government Indigenous entities and companies have been extracted

from Agency

resourcing: budget paper no. 4: 2023–24, ‘Part 2: Staffing of Agencies’

(pp. 153–164), and previous years’ budget

papers. This does not include staffing for some entities which have employees that

are not public servants under the Public Service Act 1999 (principally,

the Land Councils and Outback Stores), individual statutory office holders

attached to the NIAA (but their office staff are included), the NNTT, or the

other non-PM&C, non-incorporated statutory or advisory bodies listed above.

Figures are full-time-equivalent Average Staffing Levels (ASL).

It should be noted that many agencies have increased

reported staffing numbers in 2023–24 as a result of government policy to

convert non-APS contractors into permanent APS positions (Budget

paper no. 4, p. 154). Thus an increase in listed ASL may not

represent an increase in actual people employed.

To provide a point of comparison, information on the

entire Australian Government ASL (excluding military and reserves) is also

included. Listed Indigenous bodies currently include 1.41% of all non-military

Australian Government public servants.

Table 1 Australian

Government Indigenous body public servant Average Staffing Levels (ASL)

|

ASL

|

2021–22

|

2022–23

|

2023–24

|

|

Aboriginal Hostels Limited

|

337

|

325

|

367

|

|

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander Studies

|

142

|

142

|

141

|

|

Indigenous Business Australia

|

203

|

229

|

229

|

|

Indigenous Land and Sea Corporation

|

195

|

195

|

195

|

|

National Indigenous

Australians Agency

|

1,169

|

1,294

|

1,414

|

|

Northern Territory Aboriginal Investment Corporation

|

-

|

12

|

37

|

|

Outback Stores Pty Ltd

|

167

|

167

|

172

|

|

Torres Strait Regional Authority

|

140

|

154

|

159

|

|

Total

|

2,353

|

2,518

|

2,714

|

|

All Australian Government non-military ASL

|

181,122

|

181,062

|

191,861

|

|

Indigenous-specific ASL

from listed agencies as % of Australian Government ASL

|

1.30%

|

1.39%

|

1.41%

|

Source: Australian Government,

Agency resourcing: budget paper no. 4: 2023–24, p. 162, and previous years.

Body functions, budgets and staff

This section of the paper collates

and quotes the official descriptions of each agency’s function and intended

outcome(s), derived from relevant Portfolio budget statements and annual

reports – in particular the Prime Minister

and Cabinet Portfolio budget statement 2023–24 (PM&C PBS) – and their

allocated budgets and staff, as found in Portfolio budget statements (PBSs), Budget

paper no. 4, and annual reports.

All Australian government corporations and entities are

subject to the Public

Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) and

regular auditing

by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO).

Prime

Minister and Cabinet portfolio bodies

National Indigenous Australians Agency

The National

Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA) was established as an

Executive Agency commencing on 1 July 2019. It is a non-corporate

Commonwealth entity subject to the PGPA Act.

The NIAA is responsible for leading and coordinating the

Australian Government’s policy development, program design and implementation,

and service delivery for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. It

provides advice on whole of government priorities for Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander people to the Prime Minister, the Minister for Indigenous

Australians, the Assistant Minister for Indigenous Australians, and the Special

Envoy for Reconciliation and the implementation of the Uluru Statement from the

Heart (PM&C

PBS, p. 10).

Outcome: Lead the development and implementation of

the Australian Government’s agenda to support the self-determination and

aspirations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities

through working in partnership and effectively delivering programs (PM&C PBS,

p. 197).

The NIAA also provides staffing, budget and administrative

support for the statutory office holders listed below.

2023–24 Budget: In 2023–24, the NIAA has budgeted

$2,223.5 million to deliver programs and services for Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander peoples across its 6 programs, and $371.6 million on

departmental expenses (salaries, rental, running expenses, etc), for a total

expenditure of $2,595.1 million (PM&C PBS,

pp. 202–4). The NIAA also received $11 million in appropriations for

capital and equity (PM&C PBS,

p. 218).

The $2,223.5 million program expenditure includes:

- $1,793.1

million in grants

(including funding for ATSILS, NTRB/SPs and RNTBCs)

According to the NIAA’s

Senate Estimates briefings (pp. 17–19), in 2022–23, 73% of activity funding

(by value) and 69.7% of activities (by number) went to Aboriginal or Torres

Strait Islander organisations. These figures first rose above 50% in 2019.

The total 2023–24 resourcing of the NIAA is $4.3

billion (PM&C

PBS, p. 193), which is significantly higher than its expenditure.

This higher figure is sometimes

quoted as ‘the’ NIAA budget. The difference between the resourcing and

expenditure figures largely consists of the capital balance within the various

special accounts managed by the NIAA, principally the ABA (Budget

paper no. 4, p. 146; the NIAA

Annual Report 2021–22 ABA financial statement indicates a capital balance

of over $1.4 billion), most of which have dedicated statutory purposes, rather

than being available for program expenditure in any one year. Using the

‘resourcing’ figure thus presents an inaccurate picture of actual recurrent Indigenous-specific

expenditure.

Staffing: The NIAA is projected to employ 1,414 ASL

in 2023–24.

Statutory office

holders

The Aboriginal

Land Commissioner is an independent statutory office holder under the Aboriginal Land

Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976. The Commissioner’s principal

function is to conduct formal inquiries into applications for claims to

traditional Aboriginal land in the Northern Territory, and to provide

recommendations to the Minister for Indigenous Australians for the grant of

land to traditional owners where appropriate (PM&C PBS,

p. 8).

In 2021–22

(p. 50), the Commissioner’s expenditure was $0.4 million. The staffing and

expenditure of the office of the Commissioner are included in the NIAA’s

staffing and expenditure (above).

The Executive

Director of Township Leasing (EDTL) is an independent statutory office

holder under the Aboriginal

Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976. Its primary function is to

hold leases over townships on Aboriginal land in the Northern Territory

following agreement between the Australian Government and the respective

Aboriginal Land Council and Land Trust, and to administer sub-leases and other

rights and interests derived from such leases (PM&C PBS,

p. 9). The EDTL is funded from the ABA, not the NIAA’s departmental budget

appropriation, but its office staff are considered NIAA staff.

In 2021–22

(pp. 32, 35), the EDTL employed 13 staff in the Office of Township

Leasing, expended $3.5 million, and took in $2.7 million in Township Lease

revenue. These figures are included in the NIAA’s staffing and budget along

with other ABA expenditure.

The Office

of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations (ORIC) supports the Registrar

of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Corporations, an independent statutory

office holder responsible for administering the Corporations

(Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006 (CATSI Act).

‘ORIC supports and regulates the corporations that are

incorporated under the CATSI Act. It provides a tailored service that responds

to the special needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups and

corporations, and strives for national and international best practice in

corporate governance. It offers advice on how to incorporate, delivers training

for directors, members and key staff in good corporate governance, makes sure

corporations comply with the law, and intervenes when needed.’

In 2020–21

(the most recent ORIC Yearbook available), ORIC employed 34.5 ASL and had a

total budget of $8.4 million (pp. 7, 10). These figures are included in

the NIAA’s staffing and budget.

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander Studies

The Australian

Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) is

an independent statutory authority established by the Australian

Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Act 1989.

AIATSIS is a national collecting institution and research agency that creates

unique research infrastructure for Australia, to build pathways for the

knowledge of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to grow and be shared

(PM&C PBS,

p. 8).

Outcome: Further understanding of Australian

Indigenous cultures, past and present, through undertaking and publishing

research, and providing access to print and audio-visual collections (PM&C PBS,

p. 74).

2023–24 Budget: $22.6 million appropriated, $10.8

million external revenue, $0.3 million equity injection (PM&C PBS,

p. 71).

Staffing: AIATSIS is projected to employ 141 ASL in

2023–24.

Indigenous Business Australia

Indigenous

Business Australia (IBA) is a corporate Commonwealth entity established

under the Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander Act 2005. IBA creates opportunities for

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities to achieve

economic independence and ensure they are an integral part of the economy. It

assists Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to buy their own home, own

their own business and to invest in commercial ventures and funds that generate

financial returns and can also provide employment, training and supply chain

opportunities (PM&C

PBS, p. 9).

Outcome: Improved wealth acquisition to support the

economic independence of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples through

commercial enterprise, asset acquisition, construction and access to

concessional home and business loans (PM&C PBS,

p. 147).

2023–24 Budget: $9.4 million appropriated, $209.3

million external revenue (mostly from returns on home and business loans),

$22.8 million equity injection (PM&C PBS,

p. 144).

Staffing: IBA is projected to employ 229 ASL

in 2023–24.

Indigenous Land and Sea Corporation

The Indigenous

Land and Sea Corporation (ILSC) is a corporate Commonwealth entity

established under the Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander Act 2005. The ILSC assists Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander people to realise the economic, social, cultural and

environmental benefits the ownership and management of land, fresh water and

salt water can bring. These include economic independence (in particular

support for enterprise and jobs for Indigenous people); social benefits;

cultural identity and connection and environmental sustainability. The ILSC

provides assistance through direct investment in projects, supporting

capability development and through enabling the establishment of beneficial

networks and partnerships (PM&C PBS,

p. 9).

Outcome: Enhanced socio-economic development,

maintenance of cultural identity and protection of the environment by

Indigenous Australians through the acquisition and management of land, water

and water related rights (PM&C PBS,

p. 174).

2023–24 Budget: $9.8 million appropriated, $81.3

million external revenue (PM&C PBS,

p. 171).

The ILSC’s external revenue comes principally ($62.2

million) from dividends from the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Land and

Sea Future Fund, which is managed by the Future

Fund Board of Guardians. This revenue is included in NIAA expenditure

(above) as the NIAA manages the Special Account for the Fund. Other external

revenue sources include Voyages

Indigenous Tourism Australia, a wholly owned tourism business, and pastoral

businesses owned by the ILSC.

Staffing: The ILSC is projected to

employ 195 ASL in 2023–24.

Torres Strait Regional Authority

The Torres

Strait Regional Authority (TSRA) is a corporate Commonwealth entity

established under the Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander Act 2005. The TSRA formulates, implements, and

monitors the effectiveness of, programs for Torres Strait Islander and

Aboriginal people living in the Torres Strait, and also advises the Minister

for Indigenous Australians about issues relevant to Torres Strait Islander and

Aboriginal people living in the Torres Strait region. The TSRA works to empower

Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal people living in the Torres Strait to

determine their own affairs based on the ailan kastom (island custom) of

the Torres Strait (PM&C PBS,

p. 11).

The Chair of the TSRA is also a statutory member of the Torres Strait Protected Zone Joint

Authority, a statutory body which regulates fishing in the Torres

Strait under the Torres

Strait Fisheries Act 1984.

Outcome: Progress towards Closing the Gap for

Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal people living in the Torres Strait Region

through development planning, coordination, sustainable resource management,

and preservation and promotion of Indigenous culture (PM&C PBS,

p. 283).

2023–24 Budget: $37.2 million appropriated, $17.7

million external revenue (PM&C PBS,

p. 280).

Staffing: The TSRA is projected to

employ 159 ASL in 2023–24.

Northern Territory Land Councils

The Anindilyakwa Land Council (ALC), Central

Land Council (CLC), Northern Land Council (NLC) and Tiwi Land

Council (TLC) are the 4 Northern

Territory Land Councils established under the Aboriginal Land

Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976. The Land Councils are corporate

Commonwealth entities established to represent Aboriginal interests in a range

of processes under the Act (PM&C PBS,

p. 10).

Objective: Represent Aboriginal interests in

various processes under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act

1976. The CLC and NLC are also the Native

Title Representative Bodies for the Northern Territory under the Native Title Act

1993.

2023–24 Budget: The PM&C

Portfolio budget statement states (p. 222) that ‘Payments associated with

Land Councils’ will total $226.7 million in 2023–24. These payments to the Northern

Territory Land Councils derive from the ABA, and are included in the NIAA

expenditure above. The CLC and NLC also receive grants from the NIAA for acting

as Native Title Representative Bodies for the Northern Territory, which are

included in the NIAA’s expenditure above. All 4 Land Councils also receive

grants to employ ranger groups, provide environmental services, and for other

purposes, for the most part from the NIAA.

Staff: Land Council employees are not public

servants under the Public Service Act 1999. According to their most

recently available annual reports, staff employed were as follows:

- At

30

June 2022 (p. 32), the ALC had 151 employees.

- In

2021–22

(p. 8), the CLC employed 266 full-time-equivalent staff.

- In

2021–22

(pp. 79–80), the NLC employed ‘347 full-time or part-time employees’ and an

additional approximately 150 casual employees ‘to support seasonal workloads in

the dry season’.

- In

2021–22

(p. 90), the TLC had 8 employees.

Wreck Bay Aboriginal Community Council

The Wreck Bay

Aboriginal Community Council (WBACC) is a corporate Commonwealth

entity established by the Aboriginal Land and

Waters (Jervis Bay Territory) Act 1986.

Objective: Hold title to land and provide council

services to the Aboriginal Community of Jervis Bay (PM&C PBS,

p. 11).

WBACC also jointly manages Booderee

National Park and Botanic Gardens with the Director of National Parks.

Budget: The most recent available Annual Report for

the WBACC is for 2021–22.

Its budget includes $4.8 million received from the Australian Government as

part of the NIAA grant program, and $2.3 million in own-source revenue (p.

66).

Staff: WBACC employees are not public

servants under the Public Service Act 1999. In 2021–22

(p. 47), the WBACC had 39 full-time and part-time ongoing employees.

Northern

Territory Aboriginal Investment Corporation

The Northern

Territory Aboriginal Investment Corporation (NTAIC) is a Commonwealth

corporate entity under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act

1976. It was created by the Aboriginal Land

Rights (Northern Territory) Amendment (Economic Empowerment) Act 2021,

in order to productively invest, and grant Aboriginal peoples of the Northern

Territory control over, approximately 50% of the accumulated balance of the ABA.

The NTAIC’s purpose is to ‘empower Aboriginal people to

activate the economic potential of their land and strategically invest in their

communities and businesses to grow wealth for generations to come. The NTAIC

will use ABA funding to support the economic, cultural, and social aspirations

of Aboriginal people in the NT, whilst generating a modest financial return for

reinvestment. The NTAIC will also administer beneficial grant programs.’ (PM&C PBS,

p. 10).

Objective: To assist cultural maintenance and

social well-being, economic self-sufficiency and self-management for the

betterment of Aboriginal people living in the Northern Territory through

investments, commercial enterprise, beneficial payments and other financial

assistance (PM&C

PBS, p. 13).

2023–24 Budget: $75.4 million external revenue

($72.2 million transfer of funds from the ABA for purposes of a grant program,

returns on investments) (PM&C PBS,

p. 222, Budget

paper no. 4, p. 97). In addition, a capital transfer of $500

million from the ABA to the NTAIC will take place in this financial year (PM&C PBS,

p. 223).

Staffing: The NTAIC is projected to

employ 37 ASL in 2023–24.

Aboriginal Hostels Limited

Aboriginal

Hostels Limited (AHL) is a Commonwealth company subject to the Corporations Act

2001 and the PGPA Act. AHL provides temporary accommodation to First

Nations people through a national network of accommodation facilities. AHL

provides safe, culturally appropriate and affordable accommodation that

supports First Nations people to access education, health services and economic

opportunities (PM&C

PBS, p. 8).

Outcome: Improved access to education, employment,

health and other services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

travelling or relocating through the operation of temporary hostel

accommodation services (PM&C PBS,

p. 54).

2023–24 Budget: $43.1 million appropriated, $21.2

million external revenue, $3 million equity injection (PM&C PBS,

p. 51, Budget

paper no. 4, p. 95).

Staffing: AHL is projected to employ 367 ASL

in 2023–24.

Outback Stores Pty Ltd

Outback Stores

Pty Ltd (OBS) is a Commonwealth company subject to the Corporations Act

2001 and the PGPA Act. OBS promotes food security, health and

employment in remote Indigenous communities by managing community stores. OBS

helps Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to improve their standard of

living and achieve health goals through increasing access to affordable healthy

food and the provision of quality retail management services for community

stores (PM&C

PBS, p. 11).

Objective: To improve access to affordable, healthy

food for Indigenous communities, particularly in remote areas, through

providing food supply and store management and support services (PM&C PBS,

p. 14).

2023–24 Budget: $19.3 million external revenue.

Outback Stores is usually self-funding (Budget

paper no. 4, p. 97).

Staff: OBS is projected to employ 172 ASL in 2023–24.

In 2021–22

(pp. 46–47), OBS employed 154 full-time and 2 part-time staff as public

servants under the Public Service Act 1999, and 366 non-public servant store

employees, of whom 313 were Indigenous.

Attorney-General’s

portfolio bodies

National

Native Title Tribunal

The National

Native Title Tribunal (NNTT) is an independent body established under

the Native Title

Act 1993, but is part of the Federal Court of Australia (FCA) for

corporate administrative purposes. The NNTT and the Native Title

Registrar have a wide range of functions,

which are summarised in the FCA’s Corporate

Plan 2022–23 (p. 8):

The National Native Title Tribunal has numerous functions

designed to assist in serving that purpose [of the Native Title Act]. In

particular, it has responsibilities in connection with the processing of

applications for determinations as to the existence or non-existence of native

title over identified parcels of land, and with applications for compensation

payable pursuant to the Native Title Act 1993.

The National Native Title Tribunal has functions in

connection with future acts as defined in section 233 of the Native Title

Act 1993.

The functions also include post-determination assistance to

common law holders and their corporations to provide conflict resolution that

assists in achieving outcomes from the determined native title.

Purpose: ‘… [t]o perform the functions conferred

upon it by the Native Title Act in accordance with the directions contained in

section 109, ethically, efficiently, economically and courteously, thus

advancing the purposes underlying the Native Title Act, particularly

reconciliation amongst all Australians’ (FCA

Corporate Plan 2022–23, p. 13).

Staffing and budget: The NNTT’s staffing and budget

are included in that of the FCA. In 2021–22

(p. 90), the NNTT budget was $8.1 million. Separate staffing figures

are not available.

Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner

The Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner is a statutory

office holder in the Australian Human

Rights Commission (AHRC) under the Australian Human

Rights Commission Act 1986 (AHRC Act).

Purpose: Under the AHRC Act, the Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner may report to the minister

on the exercise and enjoyment of human rights of Indigenous peoples and

undertake social justice education and promotional activities.

In addition, the commissioner may report under the

Native Title Act 1993 on the operation of the Native Title Act and its

effect on the exercise and enjoyment of human rights of Indigenous peoples. In

addition, the commissioner reports, when requested by the minister, on any

other matter relating to the rights of Indigenous peoples under this Act (AHRC

Annual Report 2021–22, p. 13).

Staffing and budget: The commissioner’s staffing

and budget are included in that of the AHRC. Separate staffing and budget

figures are not available.

Department

of Health and Aged Care bodies

The Department of Health and Aged Care (DHAC)

administers the Indigenous

Australians’ Health Programme. In 2023–24, DHAC

will spend an estimated $1,219.4 million on Indigenous-specific health programs

and grants

(including funding ACCHOs).

Statutory board

The Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander Health Practice Board of Australia

technically operates under uniform state legislation passed by all states and

territories rather than a Commonwealth Act, but is administered by DHAC. It

regulates Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health practitioners.[4]

Non-statutory

advisory groups

Department

of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the

Environment and Water (DCCEEW) administers a number of Indigenous-specific

Acts and programs, including the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

Heritage Protection Act 1984 and associated heritage

programs, and Indigenous-specific parts of

the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC

Act). DCCEEW and the NIAA jointly administer the Indigenous

Protected Areas program. The Director of National Parks, who co-manages 3

Commonwealth National Parks owned by Traditional Owners, and the Murray Darling

Basin Authority, which administers the Water Act 2007,

also report to ministers in this portfolio.

Statutory boards

and committees

These committees have majority or entirely Indigenous

membership, and have statutory functions to provide management or advice under

an Act.

The EPBC Act Indigenous

Advisory Committee provides advice to the Minister for the Environment

on the operation of the EPBC Act, taking into account the significance of First

Nations peoples’ knowledge of the management of land and sea and the

conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity.

The Kakadu,

Uluru-Kata

Tjuta and Booderee

National Parks Boards of Management have majority representation of the

Traditional Owners of these national parks, and jointly manage them with the

Director of National Parks. Aboriginal members of the Booderee Management Board

overlap with Wreck Bay Aboriginal Community Council.

Boards and committees

with statutory Indigenous members

These committees have a range of statutory functions which

include both non-Indigenous-specific and Indigenous-specific matters. As such,

they have a statutory requirement to include one or more Indigenous members.

The Australian

Heritage Council is a body of heritage

experts established by the Australian

Heritage Council Act 2003, which provides independent advice to

the minister on heritage-related matters. It is required to include 2 Indigenous

persons with substantial experience or expertise in Indigenous heritage, at

least one of whom must represent the interests of Indigenous people.

The Murray Darling

Basin Authority administers the Water Act 2007

in the Murray-Darling basin and reports to the Minister with

responsibility for water. Since passage of the Water

Amendment (Indigenous Authority Member) Act 2019, it has been required

to include an Indigenous member with a high level of expertise in Indigenous

matters relevant to Murray-Darling Basin water resources.

The Wet

Tropics Management Authority is managed by a board established under

the Wet

Tropics World Heritage Protection and Management Act 1993 (Qld).

While this board is established by Queensland legislation, it includes 2 Commonwealth-nominated

directors under the Wet

Tropics of Queensland World Heritage Area Conservation Act 1994 owing

to the World

Heritage status of the Wet Tropics. At least one Commonwealth-nominated

director is required to be an Indigenous person with appropriate knowledge of,

and experience in, the protection of cultural and natural heritage.

Non-statutory

advisory committees

Other departments,

their bodies and expenditure

Other entities with some Indigenous-specific programs or

bodies include:

With the exceptions of ABSTUDY ($352.3 million)[5]

and the Department of Defence ($22.5 million), Australian Government

Indigenous-specific expenditure within DCCEEW and other departments is not

available in PBSs after 2015–16, and can only be estimated or partially

accounted for (see Budget

Review 2023–24: Indigenous Affairs for further discussion).

However, most of these departments’ Indigenous-specific programs are or have

historically been quite small in funding terms compared to the PM&C bodies,

the Department of Health and Aged Care, and ABSTUDY. Collectively, based upon available

information from departmental PBSs, these other programs will have an estimated

total expenditure of $508.7 million in 2023–24.

National

Partnership expenditure

As well as direct expenditure, the Australian Government expends

money ‘indirectly’ through Indigenous-specific payments to the states and

territories via National Partnerships (NPs), listed in Federal

financial relations: budget paper no. 3: 2023–24. (Budget Paper no.

3). In 2023–24, these include $186.7 million for remote

Indigenous housing and infrastructure,

$16.4 million for several NPs relating to Indigenous health (Budget Paper

no. 3, pp. 33–34), and $225.2 million for other Indigenous-specific NPs and

payments, including NPs for education,

community

safety, policing,

legal aid (including ATSILS), and tourism (Budget Paper no. 3, p.

103). Historically, funding for Indigenous housing and infrastructure has been

the largest single component of NP payments.

Australian Government Indigenous-specific expenditure

overview

In 2023–24, budgeted Australian Government

Indigenous-specific expenditure, including capital and equity payments,

payments from special accounts, and National Partnerships (NPs), and excluding

external revenue, can be approximately summarised as set out in Table 2:

Table 2 Australian

Government Indigenous-specific expenditure, 2023–24

|

Expenditure category

|

Amount ($ million)

|

|

NIAA excluding transfers from

special accounts

|

$2,245.0

|

|

Indigenous corporate bodies (including NNTT), Land

Councils and special account payments

|

$502.4

|

|

Indigenous Health programs and

NPs

|

$1,235.8

|

|

Remote Indigenous Housing & Infrastructure NPs

|

$186.7

|

|

All other NPs

|

$225.2

|

|

ABSTUDY

|

$352.3

|

|

All other departments and

programs (estimate)

|

$508.7

|

|

Total

|

$5,256.1

|

Source: Parliamentary

Library calculations based on Budget papers no.s 2, 3 and 4 and departmental Portfolio

budget statements, 2023–24.

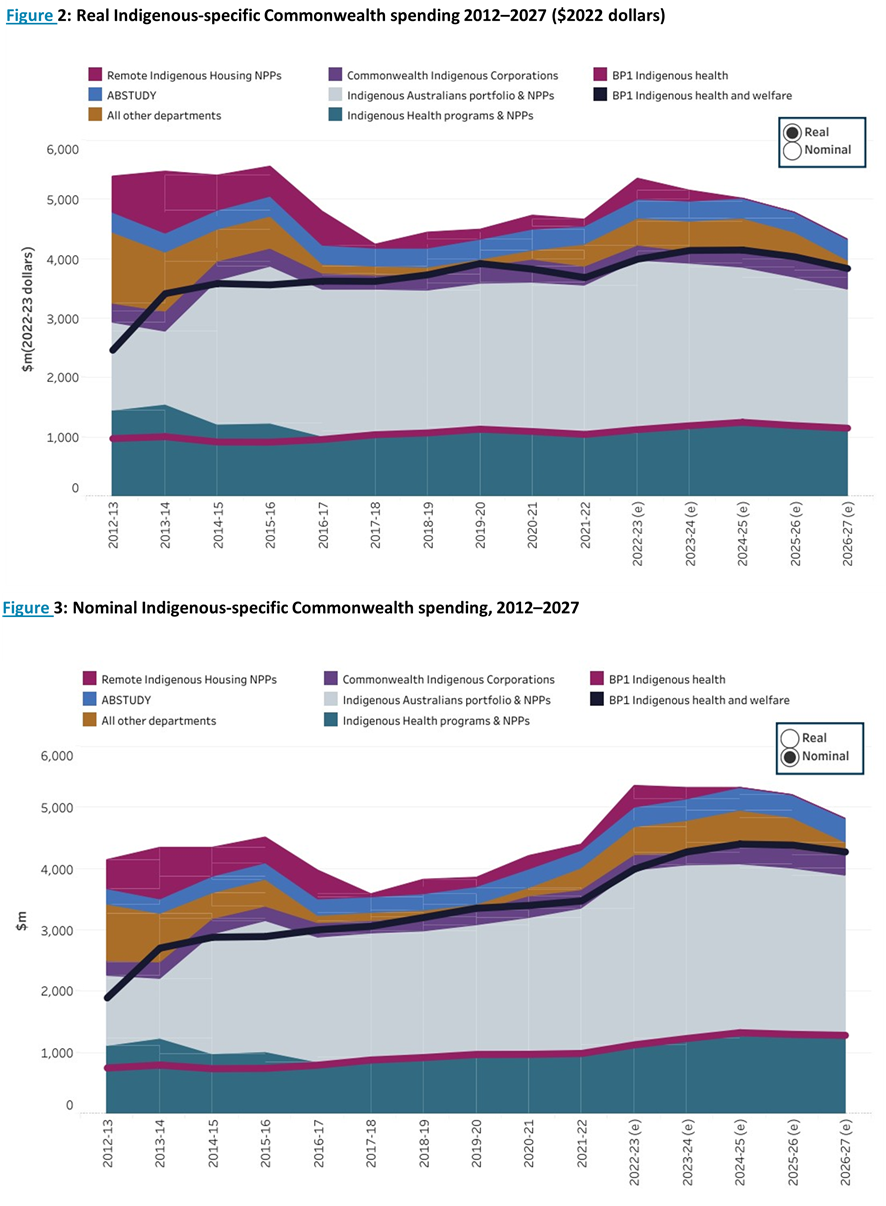

The estimated total expenditure by the Australian

Government on all Indigenous-specific programs across all departments in

2023–24 will be $5.3 billion. In real terms, this is approximately the same as

expenditure per year in the period 2012–2016 (see Figure 2 below). For context,

$5.3 billion is 0.77% of the Australian Government’s total $684.1

billion budgeted expenditure, and does not appear in the top

20 expenditure items of the Budget. The Australian

Bureau of Statistics estimates that there are approximately 983,700

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, representing 3.8% of the total

Australian population.

For previous years, the Library’s 2023–24

Budget Review: Indigenous Affairs includes a graph over time of

estimated nominal and real Indigenous-specific Australian Government spending

from 2012 to forward estimates, which is reproduced below.[6]

For discussion of this graph, see the Budget Review. For years before

2012, see the 2012 Library research paper Commonwealth

Indigenous-specific expenditure 1968 – 2012.[7]

[1].

Statutory office bearers are not individually subject to the PGPA Act, but

have their own reporting requirements under their governing Act(s).

[2].

The NTAIC commenced operations on 15 November 2022. As such, not all

operating details will be available until it has prepared its first annual

report. Not all employees of the NTAIC are public servants.

[3].

Payment of mining withholding tax on royalty-equivalent payments to

traditional owners, Land Councils, and ABA grant recipients was introduced in

1979. The tax is paid by the NIAA prior to distribution of royalty-equivalents

to recipients. It has often been criticised as inequitable, as it results in an

income tax being levied on people whose income is otherwise below the tax-free

threshold; see for example Fiona Martin and Binh Tran-Nam, ‘The

mining withholding tax under Division 11C of the Income Tax Assessment Act

1936: it may be simple but is it equitable?’, Australian Tax Forum

27, no. 1 (2012): 149–74, 168.

[4].

Practitioners of traditional and complementary Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander medicine and health practices, not medical doctors who happen to be

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander persons.

[5].

ABSTUDY recipients cannot receive Austudy or Youth Allowance, for which many

recipients would be eligible if ABSTUDY did not exist. Thus, ABSTUDY in large part

substitutes for non-Indigenous-specific expenditure, rather than adding to it. Similar

considerations apply to spending on Indigenous housing (which partly substitutes

for general social housing programs) and Indigenous-specific health programs.

[6].

The spending subcategories in the graphs below are not the same as those

used in Table 2. Specifically, National Partnerships (other than housing and

health) and special account payments are categorised under ‘Indigenous

Australians portfolio & NPPs’. Overall totals are calculated on the same

basis.

[7].

This paper does not include Indigenous-specific National Partnership

payments in the period 2007–2012.

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.

In essence, you are free to copy and communicate this work in its current form for all non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the work to the author and abide by the other licence terms. The work cannot be adapted or modified in any way. Content from this publication should be attributed in the following way: Author(s), Title of publication, Series Name and No, Publisher, Date.

To the extent that copyright subsists in third party quotes it remains with the original owner and permission may be required to reuse the material.

Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of the publication are welcome to webmanager@aph.gov.au.

This work has been prepared to support the work of the Australian Parliament using information available at the time of production. The views expressed do not reflect an official position of the Parliamentary Library, nor do they constitute professional legal opinion.

Any concerns or complaints should be directed to the Parliamentary Librarian. Parliamentary Library staff are available to discuss the contents of publications with Senators and Members and their staff. To access this service, clients may contact the author or the Library‘s Central Entry Point for referral.