16 NOVEMBER 2023

PDF Version [1.33MB]

Dr Shannon Clark, Marilyn Harrington and Dr Emma Vines

Social Policy

Executive

summary

- Classroom

disruption and disruptive student behaviour is a complex and multifaceted

issue. Disruptive behaviour in schools encompasses a wide range of behaviours,

ranging from chatting in class to physical violence.[1]

Problematic student behaviour is intertwined with numerous aspects of schooling

including student engagement, classroom management practices, school learning

environments and disciplinary practices.

- Classroom

disruption can impact negatively on students and teachers. Disruptive classroom

environments are associated with poorer student performance, which can in turn

have long-term impacts on students’ lives. Disruptive student behaviour can

impact on teachers’ job satisfaction and contribute to teachers wanting to

leave the profession.[2]

- Managing

disruptive behaviour can be difficult. Classroom management is one of the most

challenging aspects of teachers’ roles, particularly for early career teachers.[3]

Furthermore, strict disciplinary practices used to manage problematic student

behaviour such as suspension or expulsion can themselves have negative impacts

on students.[4]

In Australia, exclusionary practices disproportionately affect boys, Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander students, students with disability, and those living

in out-of-home care.[5]

Contents

Executive

summary

Introduction

What constitutes disruptive behaviour

in schools?

The extent of classroom disruption in

Australia

Australia’s results in an

international context

Impacts on teachers and students

Addressing classroom disruption

Conclusion

Introduction

This paper explores issues related to

classroom disruption, including what it is, its impact on students and

teachers, and approaches to managing it. Based on students’ reports in the

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) Programme for International Student

Assessment (PISA) in 2018, the disciplinary climate in schools in Australia

is among the worst in OECD countries.[6]

Classroom disruption can impede student learning, contributing to lost teaching

time and making it difficult for students to concentrate. It can also take a

toll on teachers, contributing to a loss of job satisfaction, stress and

burnout.

In Australia, there are 2 broad school sectors: government

(also referred to as public or state schools) and non-government (also referred

to as private or non-state) schools.[7]

State and territory governments administer and operate government schools and

regulate government and non-government schools in their jurisdiction.

Non-government schools can be further distinguished as Catholic and independent

schools. Many non-government schools have a religious affiliation or promote a

particular educational philosophy. Non-government schools may be administered

as part of a system, or operate as single entities.

Schools and school authorities have policies and procedures to

guide responses to disruptive student behaviour. In response to persistent or

serious student misbehaviour, schools may employ exclusionary disciplinary

approaches such as suspensions or expulsions. However, research has found that such

punitive approaches are disproportionately applied towards students who are

disadvantaged and male students, and can themselves have negative impacts on

students.[8]

In Australia, better data is needed on suspensions and expulsions. There is no

nationally consistent data on suspensions and expulsions in government schools

and no publicly available data for non-government schools.

In this paper, we consider what constitutes disruptive

behaviour in schools and how it can be measured. We discuss examples of data

that can provide insight into the extent of classroom disruption in Australia

and overseas, as well as discussing how Australia compares to other countries

on international measures of disciplinary climate. We then examine the impact

of disruptive behaviour on students, including on student performance as well

as the impact of exclusionary discipline; and on teachers, such as teacher

safety, work satisfaction and staff retention. In the final section, we discuss

factors that contribute to students’ (mis)behaviour and strategies that may be

employed to manage and minimise classroom disruption, and present examples of

resources and approaches from Australia and selected overseas countries.

What

constitutes disruptive behaviour in schools?

There is no single definition of classroom disruption.

Disruptive behaviours can vary from low-level disruptions to more challenging

behaviours. Low-level disruptions can include students:

- talking

unnecessarily or chatting

- calling

out without permission

- being

slow to start work or follow instructions

- showing

a lack of respect for each other and staff

- not

bringing the right equipment

- using

mobile devices inappropriately.[9]

More challenging behaviours can include:

- physical

and verbal aggression

- unsafe

and dangerous behaviours.[10]

PISA uses a pragmatic definition of disciplinary climate

(discussed further below), measuring it ‘by the extent to which students miss

learning opportunities due to disruptive behaviour in the classroom’.[11]

While challenging behaviours, particularly violence and

aggression, tend to gain media attention,[12]

most classroom disruption is low-level disruption, such as talking out of turn,

and/or student disengagement.[13]

More serious or persistent disruptive behaviour may be

punishable through exclusionary practices, such as suspension or expulsion. States

and territories set out grounds for suspension and/or expulsion in government

schools in legislation and policies.[14]

However, just as there is a wide range of behaviour that can be considered

disruptive, there is considerable variation across Australia in how the grounds

for suspension and/or expulsion are specified. For example, while South

Australian legislation includes ‘persistent and wilful indifference to school

work’ as well as violence and acting illegally,[15]

Western Australian legislation broadly states that a student may be suspended

for ‘a breach of school discipline’, which is ‘any act or omission that impairs

the good order and proper management of the school’.[16]

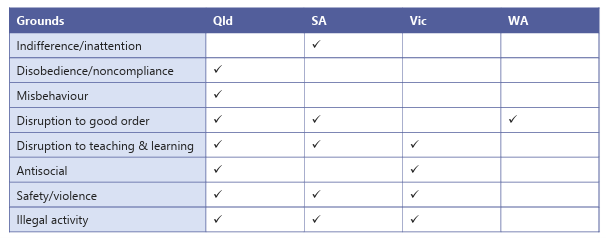

Table 1, reproduced from a study of exclusionary practices in Australia,

compares the grounds on which students in government schools may be suspended

in Queensland, South Australia, Victoria and Western Australia.

Table 1 Grounds on

which students may be suspended in Queensland, South Australia, Victoria and

Western Australia

Source: Jamie Manolev, Anna

Sullivan, Neil Tippett and Bruce Johnson, School Exclusionary Practices in Australia, School Exclusions Study Key Issues Paper No. 1

(Adelaide: University of South Australia, 2020), 2.

The

extent of classroom disruption in Australia

Because classroom disruption can take many forms, there are

also multiple ways that disruptions can be measured. In Australia, this

includes data collected as part of PISA, as well the OECD’s Teaching and Learning

International Survey (TALIS); data about the number of school exclusions,

such as suspensions and/or expulsions; and surveys of school communities’

opinions.

PISA and

TALIS – Australian results on disciplinary climate

PISA 2018

PISA is an

international assessment of 15-year-olds which measures students’ ability to

apply their knowledge in reading, mathematics, and science.[17]

PISA is a sample assessment. Participating countries select a representative

sample of schools to take part, and within those schools a representative

sample of students is selected for testing.

The Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER)

published reports of Australia’s results in PISA 2018. In 2018, 14,273 students

from 740 schools participated in PISA. Of these, 56% of students were from

government schools, 24% were from Catholic schools, and 20% were from

independent schools.[18]

Chapter 9 of PISA 2018:

Reporting Australia’s Results. Volume II Student and School Characteristics

discussed the disciplinary climate in English classes.[19]

Students were asked how frequently the following occurred in their English

classes on a 4-point scale (every class, most classes, some classes, never

or hardly ever):

- ‘students

don’t listen to what the teacher says’

- ‘there

is noise and disorder’

- ‘the

teacher has to wait a long time for students to quieten down’

- ‘students

cannot work well’

- ‘students

don’t start working for a long time after the lesson begins’.

Key findings of the report included the following for

Australian students in English classes:

- Approximately

one-fifth (21%) of students reported that in most or every class students

cannot work well, one-quarter (26%) reported that students don’t start

working for a long time after the lesson begins, approximately one-third

reported that the teacher has to wait a long time for students to quieten

down (32%) and that students don’t listen to what the teacher says

(37%).

- Almost

half (43%) of students reported that there is noise and disorder in most

or every class.

- The

disciplinary climate deteriorated between PISA 2009 and 2018, for example, there

was a 5 percentage point increase in students reporting that students

don’t listen to what the teacher says in most or every class.

- Students

in non-government schools reported a more favourable disciplinary climate than

students in government schools.

- Students

in classrooms with the most favourable disciplinary climate (the highest

quartile of the disciplinary climate index) performed higher in reading

literacy than students in classrooms with the least favourable disciplinary

climate (lowest quartile of the disciplinary climate index), scoring 55 points

higher on average – the equivalent of around one and two-thirds of a year of

schooling.[20]

As part of PISA 2018, school principals were asked about the

extent to which they perceived student behaviour hindered learning. Key

findings discussed in Chapter 10 of ACER’s report included that, on average, 50%

of principals of Australian students reported student learning was hindered to

some extent or a lot by students not being attentive, with lower

percentages reported for the perceived hinderance on learning of:

- student

truancy (33%)

- students

lacking respect for teachers (30%)

- students

skipping classes (24%)

- students

intimidating or bullying other students (23%)

- student

use of alcohol or drugs (11%).[21]

TALIS

2018

TALIS collects information about the learning environment

and working conditions of teachers and principals across the world.[22] It asks teachers to

identify a particular class chosen at random from their teaching schedule (the

‘target class’) and asks teachers questions about the class and how they teach

it.[23]

Like PISA, TALIS also looks at the classroom disciplinary environment. It asks

teachers about their level of agreement (strongly disagree; disagree;

agree; strongly agree) with statements about the disciplinary

climate in the classroom:

- ‘I

lose quite a bit of time because of students interrupting the lesson’

- ‘I

have to wait quite a long time when the lessons begin for students to quieten

down’

- ‘there

is much disruptive noise in the classroom’

- ‘students

in this class take care to create a pleasant learning atmosphere’.[24]

The Australian report for TALIS 2018 reported that, despite Australian

schools often being characterised as noisy and disruptive, there were no

differences in these areas between Australia and the OECD average (discussed

further below).[25]

Another aspect of school and classroom climate considered by

TALIS is school safety. Principals were asked about the frequency of safety-related

incidents occurring in their schools (never; less than monthly; monthly;

weekly; or daily). Australian principals reported a higher

frequency of incidents than on average across the OECD. For example:

- 37%

reported that intimidation and bullying among students occurs at least weekly

in their schools, compared with 14% of schools across the OECD

- 12%

reported that intimidation and verbal abuse of teachers and staff by students

occurs at least weekly, compared with 3% of principals across the OECD.[26]

Australian

surveys of school staff

Surveys of school staff can also provide insights into the

extent of disruptive student behaviour in schools. Findings from recent surveys

are summarised below.

Australian

Principal Occupational Health, Safety and Wellbeing Survey: This annual survey is conducted by the Australian

Catholic University. It includes principals, assistant principals, and deputy

principals from every school type, sector, state, and territory. The 2022

survey results reported an increasing trend in threatening behaviour from students

compared with 2021:

- 37.6%

of school leaders reported being exposed to threats of violence (up

4.3 percentage points from 2021)[27]

- 41.6%

reported being subjected to physical violence (up 4.5 percentage points

from 2021)[28]

Australian

Teachers’ Perceptions of their Work in 2022: This Monash

University survey had 5,497

respondents, a majority of whom were primary (41.8%) or secondary (31.5%)

teachers. The majority of respondents were from the public or state school

sector (65.7%) followed by private and independent schools (14.8%) and

faith-based schools (12.8%). The 2022 report showed that when comparing the

results from the 2019 survey, there were more teachers who felt unsafe at work in

2022, with 24.5% feeling unsafe, an increase of 5.6 percentage points since

2019.[29]

Of those who indicated that they did not feel safe at work, participants were

asked to comment on reasons why. Student behaviour and violence were key

reasons with almost two-thirds of comments provided relating to students,

suggesting that some students were ‘abusive’, ‘aggressive’, violent’ and

‘threatening’. Other reasons included abuse from parents and negative

relationships with staff.

Teachers cited particular challenges in relation to student behaviour,

including perceived lack of parent discipline at home, and ‘the rise of new and

difficult student behaviours that we don’t yet know how to deal with’.

Solutions canvassed included increased resourcing to reduce workloads and

reduce class sizes, as well as extra funding for teaching aides, social

workers, counsellors and qualified professionals to provide extra psychosocial

support for students and to support teachers, particularly in low socioeconomic

and remote schools.[30]

State of Our Schools: This is an

annual survey of Victorian government school staff (principals, teachers,

education support and casual relief teachers) conducted by the Victorian Branch

of the Australian Education Union. The 2021 survey results, based on 10,831

responses, showed:

- 41.1%

of teachers who reported increased work-related stress attributed the increase

to student behaviour[31]

- of

those who saw themselves leaving public school education in 10 years or less,

40.1% blamed student behaviour[32]

- 68.5%

of respondents considered that improved resources and processes to support

student management issues would most help to retain teachers in the profession.[33]

State and

territory data

Australian state and territory data on exclusionary

discipline (such as suspensions and expulsions) and school surveys of students’

and/or parents’ opinions can also provide insights into classroom behaviour and

schools’ disciplinary climate.

Table 2 below provides links and a brief description of the

available data by state and territory in relation to school exclusion and

school surveys.

State and territory government school suspension and

expulsion data

There is no nationally comparable data on government school

suspensions and expulsions. As such, the terminology, length and grounds for

suspensions and expulsions and the public availability and extent of the data

provided vary considerably between jurisdictions. Also, policy changes in

relation to discipline, suspensions and expulsions and the effects of the COVID

pandemic, with its lockdowns and remote learning, has affected consistency and comparability

of trend data within jurisdictions. There is also no readily available data for

non-government school suspensions and expulsions.

One of the aims of the University of South Australia’s School Exclusions Study is

to create a National Data Profile which will include a comparative

national analysis of the incidence of exclusions recorded over a 5-year period

in government schools; the reasons for exclusions; and a characteristics

profile of which groups of students are excluded.

Although jurisdictions publicly report school suspensions

and expulsions in different ways, with significant variation in the detail

provided, it is apparent from the available data that school suspensions and

expulsions are most prevalent in the middle years of secondary school (Years 8

and 9), and more prevalent for boys and students facing disadvantage and/or

marginalisation.[34]

School

suspension and expulsion data does not measure other classroom disruptions

which do not result in these exclusions. Some other indicators of classroom

behaviour are provided by survey data.

School

surveys

Schools have access to the School Survey, a data

collection tool launched in 2013 after being developed by Education Services

Australia and approved by the then ministerial Standing Council on School

Education and Early Childhood (SCSEEC; now Education Ministers Meeting). The SCSEEC

approved the use of agreed student and parent survey items to gather and analyse

school opinion information. The results of school opinion surveys are then made

available to schools and their communities, but aggregated data are not always

reported publicly.

Table 2 Availability of state and territory government

school exclusion and school survey data

|

State/ Territory

|

School exclusion data[35]

|

School surveys

|

|

ACT

|

Suspension

data is provided by school level (primary, secondary and college) and

includes the number of suspension incidents, rate per 100 students, number of

suspension days, number of students suspended and suspension rate as a

percentage of enrolments.

- In

2021, the suspension rate was 1.3% for primary schools, 5.7% for high

schools, and 0.8% for colleges (Years 11 and 12).

|

Parents and caregivers, students in Years 4 to 12 and

school staff provide feedback through the annual School

Satisfaction and Climate Survey. Only brief results for the ACT are published.

School principals decide

about distribution of school level results.

|

|

NSW

|

Suspensions

and expulsions data is disaggregated by suspension type (short and long),

school level (primary and secondary), aggregated years (K–2, 3–6, 7–10,

11–12) and gender. Data is also provided for Indigenous students, students

with disability and students by geolocation. Total exclusions over time are

presented graphically.

- In

2021 (full

year data), 1.5% of primary students and 8.5% of secondary students

received suspensions (of any length); 12.6% of Aboriginal students received

suspensions, and 10.3% of students identified as receiving adjustments due to

disability received a suspension.[36]

|

The Tell

Them From Me surveys of students (Years 4 to 12), teachers and parents

aim to measure student engagement and wellbeing. Aggregated data do not

appear to be publicly released.

|

|

NT

|

Routinely published

school suspensions data is minimal, only providing the number of students

suspended by region. However, detailed data are provided in the recent

report, Occupational

Violence and Aggression in Northern Territory Government Schools (October

2022).

- In

2021 the suspension rate per 1,000 students was 6.8 for non-Aboriginal

students and 14.4 for Aboriginal students (see pp. 26–29 for more

detailed data).

|

The annual Northern

Territory Government School Survey collects the opinions of staff,

students (Years 5 to 12), and parents and carers about school performance,

culture and services. It appears survey results are shared at the school

level, but results are not readily publicly available.

|

|

QLD

|

Data

is provided by region and student demographics, including number of suspensions

(short and long), exclusions and cancellations of enrolment by year level,

reasons for action and Indigenous status.

- In

2022, most school disciplinary absences (SDAs) were imposed on students in

Year 8, with 14,618 SDAs.

- Across

all years, Indigenous students received 18,829 SDAs in total (24.1% of total

SDAs), while non-Indigenous students received 59,169 SDAs (75.8% of total

SDAs).[37]

|

The annual

School Opinion Surveys obtain the views of parents/caregivers in all

families, students in Years 5, 6, 8 and 11, and school staff.

- The

2022

survey results found that 82% of parents and caregivers, 67% of students

and 76% of staff agreed that student behaviour was well-managed at their

school.

|

|

SA

|

Data

for suspensions, exclusions and expulsions are provided by year level.

- In

2022, the highest number of suspension incidents was for Year 8 students,

with 918 suspension incidents; students in Year 9 had the highest number of

exclusion incidents at 49 incidents. No expulsions are recorded.[38]

|

The wellbeing

and engagement collection surveys students in Years 4 to 12 about

non-academic factors relevant to learning and participation, including school

climate and experience of bullying.

- In

2023, 24% of students reported low wellbeing in relation to school

climate and 13% of students reported low wellbeing in relation to verbal

bullying.

|

|

TAS

|

Student

engagement and participation data outlines the proportion of total

students suspended by year level. A breakdown of the proportions of student suspensions

by reason is also provided.

- In

2022, the proportion of students suspended in government schools was 6.3%.

- Year

8 had the highest proportion of students suspended at 17.7%.

|

Students in Years 4 to 12 undertake the Student

Wellbeing and Engagement Survey annually.

- The

statewide

report for the survey in 2023 reported that 31% of students reported low

wellbeing in relation to school climate and 17% of students experienced low

wellbeing in relation to feeling safe at school.

|

|

VIC

|

Data

on expulsions is provided by level of education (primary and secondary),

year level, gender, and student background (Indigenous status, students with

disability, students in out-of-home care, students from migrant, refugee or

asylum seeker background), and outcomes for expelled students.

- In

2021, there were 125 expulsion incidents for primary and secondary aged

students. Of these, 97 expulsions (77.6%) were for male students; 9 (7.2%)

were for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students; and 26 (20.8%) were

for students receiving Program for Students with Disabilities funding.[39]

|

Students, parents and caregivers and staff participate in

the annual Attitudes

to School Survey. The results do not appear to be publicly available but

are provided at the school level.

|

|

WA

|

The Department of Education’s Annual Report 2022–23

provides the number and percentage of students suspended, and number of

students excluded (see p. 36).

- In

2022, 19,289 students (5.8% of total enrolments) were suspended, up from 18,068

in 2021 (5.5%).

- The

annual report also noted that suspensions and exclusions had increased

following the launch of Let’s

take a stand together, the WA Government’s plan to address violence

in schools.

|

We have not located information about a school survey in

WA schools.

|

Australia’s

results in an international context

International comparisons can be made using results from the

2018 PISA and TALIS surveys. Although Australian students’ reports of classroom

disruption in PISA 2018 were among the worst internationally and below the OECD

average, based on teachers’ reports in TALIS 2018, the disciplinary climate in

Australian classrooms was not vastly different from the OECD average.

Index

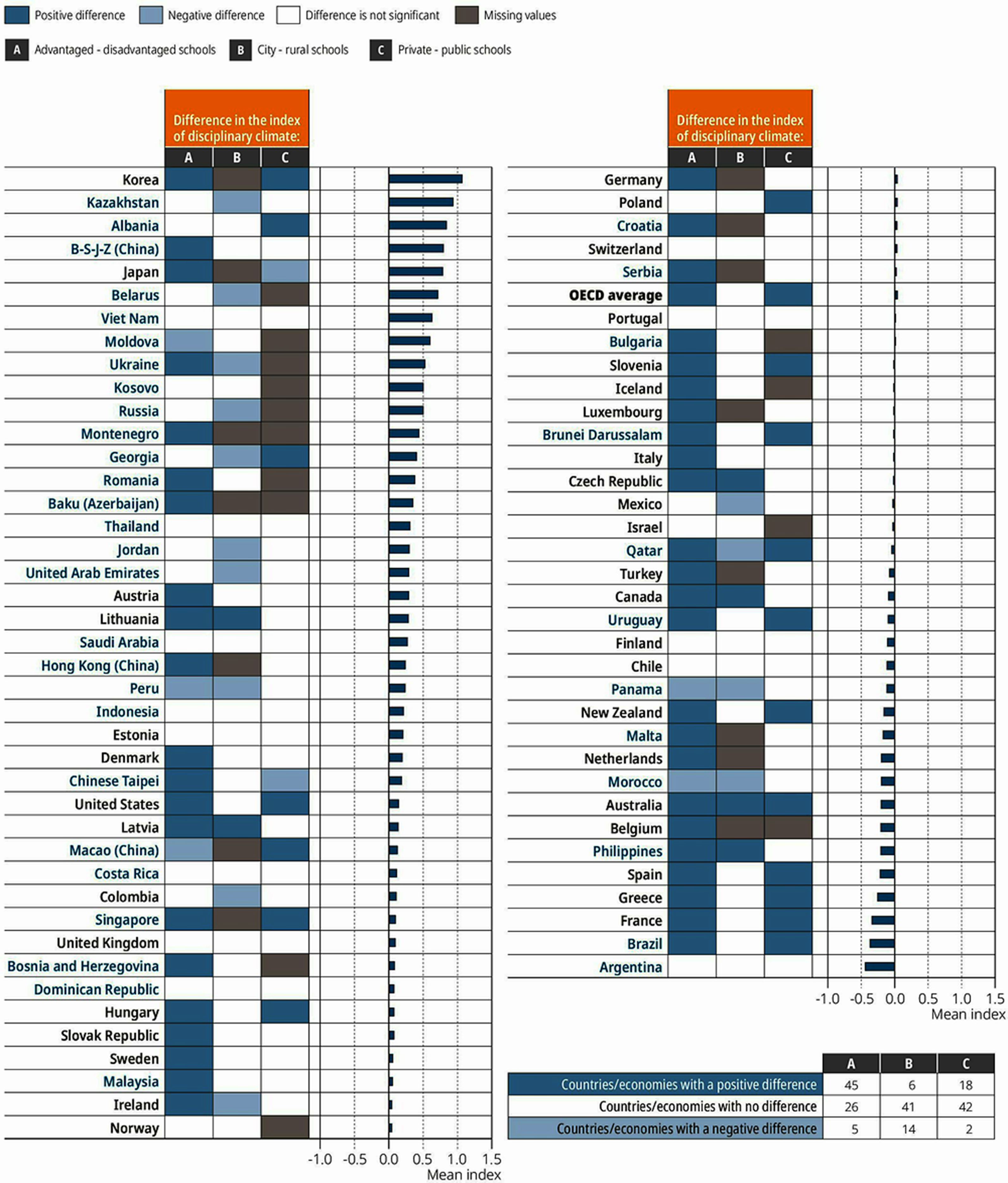

of Disciplinary Climate (PISA 2018)

According to the OECD’s 2018

index of disciplinary climate (shown in

Figure 1 below) from PISA, Australia ranked among the lowest at 70th out of 77

participating countries, with higher values in the index indicating a more

positive disciplinary climate.

The index is based on student responses to statements about

classroom disciplinary environments. The OECD

reported:

-

On

average across OECD countries, almost one in three students reported that, in

every or most lessons, students do not listen to the teacher or there is noise

and disorder.

-

Student

reports of disciplinary climate generally improved

between 2009 and 2018, especially in Albania, Korea and the

United Arab Emirates.[40]

-

In

all countries and economies, students with higher reading scores tended to

report a more positive disciplinary climate, after accounting for

socio-economic status. Even occasional disciplinary problems were negatively

associated with reading performance.

-

Student

reports of disciplinary climate were more positive in schools where more

than 60 % of students were girls and in gender-balanced schools than

in schools where more than 60 % of students were boys, on average

across OECD countries.

-

On

average across OECD countries, the positive relationship between disciplinary

climate and reading performance was relatively stable across students’ gender,

socio-economic status and immigrant background.[41]

Figure 1 Index of

disciplinary climate, by school characteristics based on students’ reports

Source: OECD, ‘Chapter 3. Disciplinary Climate’, PISA 2018 Results (Volume III): What School Life

Means for Students’ Lives, (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2019).

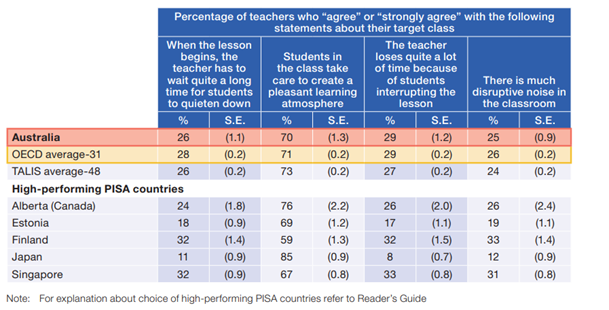

Disciplinary climate (TALIS 2018)

According to teachers’ reports in TALIS, Australian classes

are not as disruptive as students report through PISA and are not vastly

different from other countries’ classrooms (see Table 3).[42]

One reason posited for the difference between teachers’

reports and students’ reports is that PISA focuses on Year 9 students, while

TALIS reports on lower secondary school (Years 7–10), ‘so it may be that the

differences reported are less about student perception versus teacher

perception and more about the differences between Year 9 classes and Year 7–10

classes more broadly’.[43]

Table 3 Teachers’

reports of disciplinary climate internationally and for Australia

Source: Sue Thomson and

Kylie Hillman, TALIS 2018: Australian Report (Volume I): Teachers and

School Leaders as Lifelong Learners,

(Melbourne: ACER, 2019), 60.

Note: SE is Standard Error.

Impacts on teachers and

students

Impacts

on teachers

Problematic student behaviour can affect teachers’ job

satisfaction, particularly for early-career teachers. Challenging behaviours

can also contribute to teachers feeling unsafe at work and impact on their psychological

wellbeing, which in turn, can hinder long-term staff retention.

Teacher

safety, work satisfaction and workforce retention

Classroom management is one of teachers’ greatest challenges

and can contribute to burnout, job dissatisfaction and early exit from the

profession.[44]

For example, as noted above, results from the 2021

survey of Victorian government school staff showed that, of the teachers

who reported increased work-related stress, 41.1% attributed the increase to

student behaviour.[45]

Of teachers who saw themselves leaving the Victorian government school system

in 10 years or less, student behaviour was the second highest reported reason

(40.1%), behind excessive workloads (87.0%).[46]

Results from the 2022

Australian Teachers’ Perceptions of their Work survey were released by

Monash University in October 2022. According to teachers, the complexity of the

learning, behaviour and social needs of students placed additional pressures on

them in terms of workload and their perceptions of respect. Of the 5,497

teachers who responded to the survey, most reported feeling that the public did

not respect the role of teachers (70.8%) and that the profession was

unappreciated (69.2%).[47]

A quarter of teachers (24.5%) reported feeling unsafe in the workplace, with

reasons identified including student behaviour and violence and parent abuse.[48]

Additional support and time for teachers to engage productively with students

was identified as a potential way to alleviate disruptive and disrespectful

behaviour in schools, and therefore contribute to improving teachers’ feelings

of safety and wellbeing.

Loss

of instructional time because of disorder and distraction

TALIS asks teachers to report on the proportion of time they

spend on 3 types of activities: actual teaching and learning; administrative

tasks; and keeping order in the classroom.

According to TALIS 2018, Australian teachers reported

spending 78% of classroom time on teaching and learning, which was similar to

teachers in other OECD countries.[49]

On average, teachers reported spending 15% of class time keeping order in the

classroom.

Time spent on actual teaching and learning was positively

related to teacher age and experience, with teachers with more than 5 years

teaching experience spending more time on actual teaching and learning than

teachers with 5 years or less teaching experience. This was the case for

Australia and all high-performing PISA countries.[50]

However, Australia performed worst in terms of time spent

teaching by equity cohorts. The TALIS 2018 report stated:

Importantly, in terms of equity, Australian teachers in

schools with a higher proportion of disadvantaged students spent less time

teaching and learning than their colleagues in more advantaged schools. The

difference in Australia (of 9.8 percentage points) is the highest in the OECD,

and equates to about 6 minutes per hour. Over 1,000 hours of face-to-face time

at school, this is substantial. Of the high-performing PISA countries, only in

Alberta (Canada) was there a similar difference (of 7.2 percentage points).[51]

This is further exacerbated in Australia as disadvantaged

students tend to be concentrated in disadvantaged schools.[52]

Australian schools are among the most socio-economically segregated in the

world, with more than half of all disadvantaged students attending

disadvantaged schools.[53]

In 2021, students with a low socio-educational advantage status comprised 31.3%

of enrolled students at government schools and 12.8% of students at

non-government schools.[54]

Impacts on

students

Classroom disruption can negatively impact students’

performance and achievement at school, which in turn can have long-term impacts

on education and employment. However, strict disciplinary approaches to student

behaviour, such as exclusionary practices, disproportionately affect particular

groups of students and can also have negative impacts on students in later

life.

Student achievement

Research findings have highlighted the association between

orderly learning environments and student achievement.[55] Results from PISA 2018 showed

that students who reported a better disciplinary climate performed better in

reading, after accounting for the socio-economic profile of schools and

students.[56]

On average across the OECD, a unit increase in the index of disciplinary

climate – where higher values indicate a more positive disciplinary climate – was

associated with an increase of 11 points in reading performance.[57]

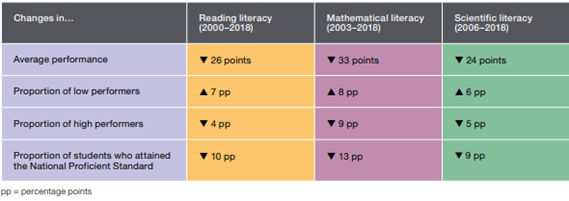

Australian students’ performance in PISA assessments has

been declining since the international standardised assessment began in 2000. While

the reasons for the decline are complex, numerous facets of the education

system, including classroom disruption, have been posited as contributing

factors.[58]

The PISA 2018 results show Australia’s PISA scores have been steadily declining

in all 3 assessment domains (reading, mathematics and science), as set out in

Figure 2.[59]

Figure 2 Australian

achievement in PISA since 2000, measured from the first cycle in which a

subject was the major focus domain

Source: ACER, ‘PISA 2018: Australian students’ performance’, ACER Discover, 3 December 2019.

As depicted in Table 4, the Australian

results also show:

- the

proportion of low performers has increased and the proportion of high

performers has decreased in each domain

- the

proportion of students who attained the National Proficient Standard has

declined in all domains.[60]

Table 4 Changes in

performance over time for Australia

Source:

Sue Thomson et al., PISA in Brief 1: Student Performance, (Melbourne: ACER), 7.

The results of PISA

2022 are expected to be released at the end of 2023.

Impacts of exclusionary

discipline

As noted above, exclusionary discipline, such as

suspensions, exclusions and/or expulsion, is sometimes used in response to

student behaviour. Research has found that Australian schools’ exclusion

practices disproportionately impact boys, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

students, students with disability, students from culturally and linguistically

diverse backgrounds, and those living in out-of-home care.[61] For example, data from 2019

showed the following:

Indigenous students

-

In Queensland, Indigenous students

received a quarter of all fixed-term and permanent exclusions (25.3% and 25.4%

respectively), despite making up just over 10% of all Queensland’s full-time

state school enrolments.

-

In NSW, of all short and long

suspensions approximately 25% were for Aboriginal students, even though this

group represents just 8% of all student enrolments.

-

In Victoria, 6.5% of all expulsions

were for Indigenous students, however, this group represents only 2.3% of the

student population.

Students with disability

-

In Victoria, students with

disability funding received 14% of all permanent exclusions yet constituted

only 4.5% of all government school enrolments.

Male students

-

In South Australia, over three

quarters of all suspensions were given to male students (77%), a ratio of over

3:1 compared to females.

-

In Victoria, males received over

80% of the permanent exclusions, a ratio of 4:1 compared to females.

-

In NSW, around three quarters of

all short and long suspensions in 2019 were for males (75.3% and 73.9%

respectively).[62]

The risk of suspension increases with greater

intersectionality; that is, for students falling into multiple equity groups,

such as students who are Indigenous and have disability and live

in out-of-home care.[63]

Strict discipline policies and exclusionary practices can

have negative impacts for excluded students. School suspension can compound

behavioural problems and increase the likelihood of leaving school early, which

in turn can have lifelong impacts.[64]

Dr Daniel Quin from the Australian Catholic University explained:

If we consider that they were

probably already struggling academically, and that this may have been a

contributing factor to their behavioural issues, suspension of even a day can

have a major impact on the rest of their schooling.

We know that children who

have been suspended are more likely to skip school, participate in anti-social

behaviour and leave school early. In turn, early school departure is associated

with greater unemployment, diminished happiness in home life, diminished

health, higher mortality rates, and an increased association with the criminal

justice system.[65]

Dr Quin’s research into the effectiveness of school

suspensions found that suspension is likely to be applied to students who lack

the ability to self-regulate their behaviours and emotions in the classroom.

Pre-existing behavioural problems may be exacerbated by excluding students through

reducing school protective factors (such as supportive teacher relationships,

belonging and acceptance) and increasing exposure to known risk factors (such

as interaction with antisocial peers).[66]

In the 1980s and 90s, ‘zero

tolerance’ discipline policies emerged in the United States, whereby

students who broke certain school rules faced mandatory penalties including

suspension and referral to law enforcement. However, research on the impact of

such policies has found that they can stigmatise students and contribute to the

‘school-to-prison pipeline’.

Analysis by the US National Bureau of Economic Research

examined the impact of school discipline on student achievement, educational

attainment and adult criminal activity. It found that higher suspension rates in

schools have substantial negative long-run impacts on students’ lives. Students

assigned to a school with a suspension rate one standard deviation higher were

15–20% more likely to be arrested and incarcerated as adults. The study also

found negative impacts on educational attainment. Male students and students

from minority groups had the largest impacts from attending a high suspension

school.[67]

Similarly, results from the International Youth Development

Study, which studied adolescent development in Victoria (Australia) and

Washington State (US), found that school suspensions were associated with increased

likelihood of students engaging in problem behaviours, including violent and

antisocial behaviours and tobacco use.[68]

A complicating aspect of exclusionary discipline is that

strategies to reduce suspensions and expulsions and their negative impacts and

disproportionate application on vulnerable cohorts may be viewed as increasing

risks to teacher safety and reducing the options available to teachers to

manage student behaviour. For example, in September 2022, the NSW Government

updated its policy on ‘Student

discipline in government schools’, changing it to ‘Student

behaviour’. The new policy emphasised positive behaviour practices and

changed procedures for managing student behaviour, including in relation to

suspensions – reducing the maximum length for a suspension from 20 days to 10

days. The changes were designed to reduce the number of suspensions and provide

better support for students, particularly Indigenous students, students with

learning difficulties and students from low SES backgrounds.[69]

However, the changes were met with mixed reactions. While parents supported the

policy, the NSW Teachers Federation argued that it posed ‘“a significant risk”

to the health and safety of principals, teachers, support staff and students’,

and constrained teachers’ ability to manage disruptive and dangerous behaviour.[70]

Following a change in the NSW Government, the school

behaviour policy will again be updated:

An updated NSW public school behaviour policy will replace

a controversial strategy introduced under the former Coalition government

that capped the length and number of suspensions schools could issue, as well

as the grounds for which a student could be sent home.

NSW Education Minister Prue Car said a review of the former

policy, which was rolled out in term 4 last year, found it undermined teachers’

ability to protect the safety of staff and students.[71]

The new policy will be released for training and

familiarisation in Term 4, 2023, and come into effect in Term 1, 2024.[72]

Similarly, in response to increased misbehaviour in

schools in the US, a number of states are moving to make it easier for teachers

and principals to exclude misbehaving students.[73]

Such changes reverse policy reforms which were less punitive, and which were

introduced to replace the strict, ‘zero tolerance’ discipline policies. The

to-and-fro of policy reforms highlight the delicate balance that policymakers

face in managing student discipline, reducing inequitable treatment and

supporting positive behaviour, while also ensuring teachers feel safe in their

workplace and have options to effectively manage student behaviour.

Addressing classroom disruption

Numerous factors can contribute to students’ (mis)behaviour

in class, including:

- their

learning, social, and behavioural needs

- neglect,

abuse and/or trauma

- their

physiological state, for example, being hungry or tired

- medical

and psychological conditions (diagnosed or undiagnosed)

- emotional

factors including emotional regulation, boredom, lack of confidence, attention

seeking

- parenting

and home life

- relationships

with teachers and other students

- factors

relating to the curriculum, teaching and/or the classroom environment.[74]

Mobile phones and digital devices can be a source of

disruption, distraction, and cyberbullying in schools.[75]

Students’ behaviour may differ at different ages and stages of development, and

may be influenced by school composition, peer behaviour, and social

expectations.[76]

Understanding the factors that contribute to a student’s misbehaviour may point

to ways to alleviate and address disruptive behaviour.

Professor Linda Graham (Queensland University of

Technology) and colleagues state that:

Research has shown severely disruptive behaviour is affected

by a process of “cumulative continuity”, where children’s early characteristics

(self-regulation, temperament, academic and verbal ability) interact with their

school/classroom environment, resulting in a “snowball effect”. Difficulties

adjusting to the demands of school can result in poorer quality teacher-child

interactions and mutually reinforcing negative relationships, which in turn

compound learning and behavioural difficulties.[77]

Professor Graham notes that a common perception is that

children’s behaviour affects their learning. While acknowledging that this may

be true for some children, she cautions that ‘it is equally possible that

underlying learning difficulties are manifesting behaviourally’.[78]

Equipping

teachers to maintain order in the classroom

Effective classroom management is key to providing a

positive learning environment and enabling student learning.[79]

Proactive practices which reinforce expected behaviours have been found to be

more effective than reactive approaches which respond to behavioural issues

after they occur. Citing Evertson and Weinstein 2015, the Australian Institute

for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL) defines classroom

management as:

The actions teachers take to create an environment that

supports and facilitates both academic and social-emotional learning. In other

words, classroom management has two distinct purposes: It not only seeks to

establish and sustain an orderly environment so students can engage in

meaningful academic learning, it also aims to enhance students’ social and

moral growth.

Results from TALIS 2018 shed light on teachers’

self-efficacy – their belief in their ability to effectively perform the tasks

needed to achieve a goal – in terms of classroom management, instruction and

student engagement.

In terms of teachers’ beliefs about their ability to

establish an orderly learning environment and effectively manage disruptive

student behaviour, TALIS found:

- Around

90% of teachers in Australia and across the OECD reported high levels of

self-efficacy in terms of making their expectations about behaviour clear and

getting students to follow rules.[80]

- More

than 80% of Australian teachers reported high self-efficacy in controlling

disruptive behaviour in the classroom or calming a student who was disruptive

or noisy. This was lower than the average across the OECD and had declined by

more than 4 percentage points since TALIS 2013.[81]

- Fewer

(74%) Australian novice teachers (those with 5 years of experience or less)

reported being confident of their capacity to calm a student who was disruptive

or noisy, compared to more experienced teachers (84%).[82]

- Novice

teachers in Australia were less sure of their capacity to control disruptive

behaviour in the classroom relative to the OECD average.

- Novice

Australian teachers (74%) and novice teachers across the OECD (78%) reported

lower levels of confidence in their ability to control disruptive behaviour,

compared to 85% and 87% respectively for more experienced teachers.

- Teachers

felt least confident in motivating students who show little interest in

schoolwork, with only 68% of teachers reporting feeling confident of their

abilities in this area in Australia and across the OECD.[83]

- There

were also gaps between novice and more experienced teachers in terms of their

confidence to motive students with low levels of interest, with 59% of novice

teachers and 71% of more experienced teachers feeling confident in this area.[84]

Teaching standards and initial teacher education standards

National initiatives to support teachers and ensure they are

adequately prepared to maintain positive learning environments include teaching

standards and accreditation standards for initial teacher education (ITE), as

well as evidence-based resources provided by AITSL and the Australian Education

Research Organisation (AERO).

Creating and maintaining supportive and safe learning

environments is one of the Australian

Professional Standards for Teachers (APST) that teachers must demonstrate

they meet as a requirement for registration as a teacher. ITE programs are accredited

to ensure graduates can meet professional standards.

Managing challenging student behaviour is one of the focus

areas under Standard 4: Create and maintain supportive and safe learning

environments (Focus Area 4.3). The Graduate standard requires graduate

teachers to ‘Demonstrate knowledge of practical approaches to manage

challenging behaviour’. To meet the Proficient standard, teachers must

demonstrate their ability to:

Manage challenging behaviour by establishing and negotiating

clear expectations with students and address discipline issues promptly, fairly

and respectfully.[85]

National resources to support classroom management

In addition to the APST and ITE standards developed by

AITSL, national coordination and support for teachers is provided by AITSL and

AERO. For example, AITSL provides resources to support teachers and school

leaders, including on:

AERO was established

in 2021, following agreement of education ministers in 2019 to create an

education evidence institute to improve learning outcomes. AERO provides

resources on classroom

management, based on a set of standards

of evidence. Resources include:

- a

focused

classrooms practice guide, which identifies key practices for teachers:

- establish

a system of rules and routines from day one

- explicitly

teach and model appropriate behaviour

- hold

all students to high standards

- actively

engage students in their learning

- an

annotated

reference list, which provides an overview of research evidence cited

through the classroom management resources

- advice

on using

the practice in relation to implementing effective classroom management,

including:

- planning

for maximum student engagement

- high

expectations for focused classrooms

- snapshots

of practice – examples of classroom management in a variety of classrooms and

settings, including links to AITSL’s classroom management illustrations of

practice (above)

- implementation

tools, including:

State and territory resources

State and territory governments also provide resources,

support staff and professional development to support teachers to manage

student behaviour. For example, in September 2022, the NSW Government announced

the creation of a NSW Chief Behaviour Advisor to lift behaviour standards in

schools, work with schools using evidence-based practices, and advise parents

and carers on ways to support their children and reinforce behavioural

approaches through schools.[86]

Then Minister for Education and Early Learning Sarah Mitchell also confirmed

plans to increase the number of Behaviour Specialists for NSW government

schools from 70 to 200, to support the management of complex student behaviour.

The additional resources accompanied changes to the management of school

discipline (discussed above). Emeritus Professor Donna Cross was appointed as

the first Chief Behaviour Advisor in March 2023.[87]

The Victorian Government Department of Education and

Training provides advice, guidance and resources

for managing challenging behaviour in schools. This includes professional

development courses (requires departmental log-in).

The WA Government Department of Education’s Annual Report 2022–23

stated that its new Student Behaviour in Public Schools Policy had been

implemented in schools from Semester 2, 2023.[88]

Changes to the policy emphasised ‘the importance of creating safe, orderly,

inclusive, supportive and culturally responsive environments’.[89]

The report also outlined training undertaken by school staff to address

concerning student behaviour, stating that more than 2,750 school staff

completed training in de-escalation and positive handling and 5,255

participants attended Classroom Management Strategies and Positive Behaviour

Support training programs in 2022.[90]

International examples of classroom management

strategies

This section provides examples of classroom management strategies

in the United Kingdom (UK) (England), the US and Japan. These 3 countries all

ranked above the OECD average in the PISA 2018 index of disciplinary climate.

It is important to note that countries’ education systems

are complex and operate in the context of each country’s social, economic, and

cultural history and current environment. Features of some education systems

may not work in other countries’ contexts. It can also be difficult to isolate

attributes of a country’s education system which contribute to students’

academic performance. Associations between attributes of education systems and

student performance may not be causative.

United Kingdom (England)

Education in the UK is devolved, with the governments in the

nations of the UK having their own education departments. The UK Government Department

for Education is responsible for education in England.

The following are initiatives targeting student behaviour in

English classrooms:

- An

independent review of behaviour in schools, titled Creating

a culture: a review of behaviour management in schools, was undertaken

in 2017. It made recommendations to the Department for Education and Ofsted (Office

for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills) in relation to

strategies to support effective behaviour cultures.[91]

- The

Department for Education provides guidance for school staff in relation to

behaviour and discipline. This includes behaviour checklists for headteachers

and staff and links to further guidance and support, including:

- The

Department for Education funded Behaviour Hubs as a

3-year program to improve student behaviour. The program paired schools with

exemplary behaviour practices with partner schools that wanted to improve

student behaviour. The program was based on the Creating

a Culture review (above).

- A

review of school

exclusion was published in 2019. The review was ‘to explore how head

teachers use exclusion in practice, and why some groups of children are more

likely to be excluded, including Children in Need, those with special

educational needs (SEN), children who have been supported by social care, are

eligible for free school meals (FSM) or are from particular ethnic groups’.[92]

United

States

In the US, education is primarily the responsibility of

states and local districts. States and communities establish schools and

colleges, develop curricula and determine enrolment and graduation

requirements.[93]

The US Department of Education aims to

promote student achievement, foster educational excellence, and ensure equal

access.[94]

It plays a leadership role in education, collects data and disseminates

research, and focuses national attention on key educational issues.[95]

Institutes and centres funded by the US Department of

Education which are relevant to behaviour, discipline and school environment

include the following:

- The

National Center on Safe

Supportive Learning Environments (NCSSLE) is funded by the US Department of

Education’s Office

of Safe Supportive Schools. The NCSSLE provides information and assistance

to states, districts, schools and higher education institutions to improve

school climate and conditions for learning.[96]

- The

National Technical Assistance Center

on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) aims to improve

the capacity of state and local education agencies to establish, scale up and

sustain PBIS.

- PBIS

is a 3-tiered, evidence-based framework for supporting students behaviourally,

academically, socially and emotionally. Results of well-implemented PBIS

include improved social and academic outcomes, reduced exclusionary discipline

practices, and school staff feeling more effective.[97]

- The

Institute of Education Sciences (IES) is the statistics,

research, and evaluation arm of the US Department of Education. The IES

provides the What Works Clearinghouse,

which reviews research to inform evidence-based policy making. Its publications

search tool includes a topic on ‘behavior’.

Japan

Japan’s Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and

Technology (MEXT) is responsible for the education system from early childhood

to higher education at the national level. MEXT allocates funding to

prefectural and municipal authorities for schools.[98]

In order to address problem behaviour and non-attendance at

school, MEXT

states that it is:

(1) enhancing emotional education and achieving

easy-to-understand lessons and enjoyable schools, (2) improving the quality of

teachers, and (3) enhancing the education counselling system.

An article explaining the educational mental health support system

in Japanese schools states:

In general, Japanese schools have a Yogo teacher (a school

nurse) who works full time, as well as three types of mental health specialists

who work part time: school counselors, advisors, and social workers. The

regularity of visits from the three types of specialists depends on schools and

regions.[99]

The OECD’s Education

Policy in Japan: Building Bridges towards 2030 (July 2018) suggests

that Japan’s relatively positive disciplinary climate may not be attributable

to a single program, but rather to a broader culture of engagement with

schooling. The OECD report states that Japanese parents have a strong

commitment to students’ self-discipline and belief in students’ ability to

learn, and that they regularly engage with teachers about student progress and

behaviour.[100]

Japanese schools report low rates of truancy and lateness, and higher than

average engagement of schools and teachers with students.[101]

Conclusion

Classroom

disruption is a complex problem that incorporates aspects of school discipline,

student learning, classroom management, equity, and student and teacher

wellbeing and safety. Strict disciplinary approaches, including exclusionary

practices, are often employed to manage more serious and persistent student

misbehaviours; however, such approaches can themselves have negative impacts

and have been found to disproportionately affect already marginalised students and

boys. However, less punitive strategies that aim to minimise suspensions and

expulsions may be viewed by teachers and principals as limiting their authority

and constraining options for managing challenging behaviours and maintaining

school safety. Research suggests that proactive approaches to teaching and

reinforcing expected behaviours are more effective than reactive approaches. To

achieve this, the research indicates the importance of ensuring that teachers

are adequately prepared, and that schools are appropriately resourced to

support students with complex learning, behavioural and psycho-social needs.

[1]. Office for

Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (Ofsted), Below

the Radar: Low-level Disruption in the Country’s Classrooms, Report No.

140157 (Manchester: Ofsted, 2014), 4.

[2]. Australian

Education Union (AEU) – Victorian Branch, State

of our School Survey Results, (Melbourne: AEU – Victorian Branch,

2021).

[3]. Anna Sullivan,

Bruce Johnson, Larry Owens and Robert Conway, ‘Punish Them or Engage Them?

Teachers’ Views of Unproductive Student Behaviours in the Classroom’, Australian

Journal of Teacher Education 39, no. 6 (June 2014).

[4]. Linda Graham,

Callula Killingly, Kristin Laurens and Naomi Sweller, ‘Suspensions

and Expulsions Could Set our Most Vulnerable Kids on a Path to School Drop-out,

Drug Use and Crime’, The Conversation, 15 September 2021.

[5]. Anna Sullivan,

Neil Tippett, Bruce Johnson and Jamie Manolev, ‘Schools Are Unfairly Targeting Vulnerable

Children with their Exclusionary Policies’, EduResearch Matters (blog),

2 November 2020.

[6]. Organisation

for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Education

Policy Outlook in Australia, OECD Policy Perspectives (Paris: OECD

Publishing, 2023), 23.

[7]. Australian

Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA), National

Report on Schooling in Australia 2021, (Sydney: ACARA, 2023), 132–3.

[8]. Sullivan et

al., ‘Schools are Unfairly

Targeting Vulnerable Children with their Exclusionary Policies’.

[9]. Ofsted, Below

the Radar: Low-level Disruption in the Country’s Classrooms, 4.

[10]. Kay Ayre and

Govind Krishnamoorthy, Trauma Informed

Behaviour Support: A Practical Guide to Developing Resilient Learners,

(Toowoomba: University of Southern Queensland, 2020), 42.

[11]. OECD, ‘Chapter

3: Disciplinary Climate’, PISA 2018 Results (Volume III): What School Life

Means for Students’ Lives, (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2019), 66.

[12]. For example,

Rebekah Cavanagh, ‘Schools

Lawless Jungles: Injury Claims over Out-of-control Students’, Herald Sun,

4 January 2023.

[13]. Linda Graham et

al., ‘The Hit and Miss of Dealing

with Disruptive Behaviour in Schools’, EduResearch Matters (blog), 9

June 2015.

[14]. Provisions

relating to discipline and/or suspension and expulsion in most state and

territory legislation only apply to government schools; the ACT’s Education Act 2004

includes provisions for suspension and expulsion for government and

non-government schools.

[15]. Education

and Children’s Services Act 2019 (SA), paragraph 76(1)(f).

[16]. School

Education Act 1999 (WA), subsection 90(1); section 89.

[17]. PISA

is usually held every 3 years; however, the planned assessments in 2021 and

2024 were postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. PISA was conducted in 2022

with results expected to be released towards the end of 2023. PISA will next be

conducted in 2025.

[18]. Sue Thomson,

Lisa De Bortoli, Catherine Underwood and Marina Schmid, PISA

in Brief I: Student Performance, (Melbourne: Australian Council for

Educational Research (ACER), 2019), 2.

[19]. PISA

2018 asked about the disciplinary climate in students’

language-of-instruction lessons. In Australia, this is English classes.

[20]. Sue Thomson,

Lisa De Bortoli, Catherine Underwood, Marina Schmid, PISA 2018: Reporting

Australia’s Results. Volume II Student and School Characteristics, (Melbourne:

ACER, 2020), 88–100.

[21]. Thomson et al.,

PISA 2018: Reporting Australia’s Results, 101–4.

[22]. TALIS 2018 was

the 3rd cycle of

the survey, with previous surveys conducted in 2008 and 2013. The 4th cycle

will be undertaken in 2024.

[23]. Sue Thomson and

Kylie Hillman, TALIS

2018: Australian Report (Volume I): Teachers and School Leaders as Lifelong Learners,

(Melbourne: ACER, 2019), 8.

[24]. Thomson and

Hillman, TALIS 2018: Australian report (Volume I), 59.

[25]. Thomson and

Hillman, TALIS 2018: Australian report (Volume I), 59–60.

[26]. Thomson and

Hillman, TALIS 2018: Australian report (Volume I), 33, 56.

[27]. Sioau-Mai See,

Paul Kidson, Herb Marsh, Theresa Dicke, The

Australian Principal Occupational Health, Safety and Wellbeing Survey 2022 Data,

(Sydney: Institute for Positive Psychology and Education, Australian Catholic

University, 2023), 28; Sioau-Mai See, Paul Kidson, Herb Marsh, Theresa Dicke, The

Australian Principal Occupational Health, Safety and Wellbeing Survey 2021 Data,

(Sydney: Institute for Positive Psychology and Education, Australian Catholic

University, 2022), 52.

[28]. See et al., Australian

Principal OHSW Survey 2022 Data, 28; See et al., Australian

Principal OHSW Survey 2021 Data, 53.

[29]. Fiona Longmuir,

Beatriz Gallo Cordoba, Michael Phillips, Kelly-Ann Allen, Mehdi Moharami, Australian

Teachers’ Perceptions of their Work in 2022, (Melbourne: Monash

University, 2022), 35.

[30]. Longmuir et al.,

Australian Teachers’ Perceptions of their Work in 2022, 38–9.

[31]. AEU – Victorian

Branch, State

of our School Survey Results, 2.

[32]. AEU – Victorian

Branch, 3.

[33]. AEU – Victorian

Branch, 4.

[34]. Anna Sullivan,

Neil Tippett, Bruce Johnson and Jamie Manolev, Understanding

Disproportionality and School Exclusions, School Exclusions Study Key

Issues Paper No. 4 (Adelaide: University of South Australia, 2020).

[35]. This table uses

the most recently available data for each state and territory.

[36]. The data for

students identified as receiving adjustments due to disability is taken from

the Nationally Consistent Collection of Data

on School Students with Disability (NCCD), an annual collection of data

about students with disability. The NSW suspensions data includes students

identified as requiring supplementary, substantial or extensive levels

of adjustment. Students who require quality differentiated teaching

practices are not included.

[37]. Parliamentary

Library calculation of percentages.

[38]. The SA

Department for Education’s ‘Suspension,

Exclusion and Expulsion of Students Procedure’ states that expulsion ‘must

be reserved for the most serious behaviours that jeopardise the safety of the

school community’ (p. 18). Under the Education

and Children’s Services Act 2019 (SA), a student can only be expelled

if they are above the compulsory school age (see sections 78 and 79); that is,

16 years and above.

[39]. Parliamentary

Library calculation of percentages.

[40]. However,

analysis of the results published in a Sydney Morning Herald article, ‘Australian students

“among the worst in the world” for class discipline’, reported Australia

was one of a minority of countries where it had deteriorated.

[41]. OECD, ‘Chapter

3. Disciplinary Climate’, PISA 2018 Results (Volume III): What School

Life Means for Students’ Lives, (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2019).

[42]. Thomson and Hillman, TALIS

2018: Australian report (Volume I),

59–60.

[43]. Thomson and

Hillman, 60.

[44]. Sullivan et al.,

‘Punish Them or Engage Them?

Teachers’ Views of Unproductive Student Behaviours in the Classroom’, 43.

[45]. AEU – Victorian

Branch, State

of our School Survey Results, 2.

[46]. AEU – Victorian

Branch, 3

[47]. Longmuir et

al., Australian

Teachers’ Perceptions of their Work in 2022, 10, 12

[48]. Longmuir et

al., 35–6.

[49]. Thomson and

Hillman, TALIS

2018: Australian Report (Volume I), 14.

[50]. Thomson and

Hillman, 14.

[51]. Thomson and

Hillman, TALIS

2018: Australian Report (Volume I), 14.

[52]. Chris Bonnor,

Paul Kidson, Adrian Piccoli, Pasi Sahlberg, and Rachel Wilson, Structural

Failure: Why Australia Keeps Falling Short of its Educational Goals

(Sydney: UNSW Gonski Institute, 2021). The OECD defines disadvantaged schools

as ‘those whose average intake of students falls in the bottom quarter of the

PISA index of economic, social and cultural status within the relevant

country/economy’,OECD, PISA

2018 Results (Volume II): Where All Students Can Succeed, (Paris: OECD

Publishing, 2019), 105.

[53]. OECD, Equity

in Education: Breaking down Barriers to Social Mobility, (Paris: OECD

Publishing, 2018), 121.

[54]. Productivity

Commission, ‘4.

School Education’, Report on Government Services 2023, (Canberra:

Productivity Commission, 2023), Table 4A.6).

[55]. Sullivan et

al., ‘Punish Them or Engage Them?

Teachers’ Views of Unproductive Student Behaviours in the Classroom’, 43.

[56]. OECD, ‘Chapter

3. Disciplinary Climate’, in PISA 2018 Results (Volume III): What School

Life means for Students’ Lives, (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2019), 69.

[57]. OECD, 69.

[58]. Wade Zaglas, ‘Poor

PISA Results Indicate a Lack of ‘Respect’ in Australian Classrooms’, Education

Review, 9 December 2019.

[59]. The ability to

establish and maintain trends over time is one of PISA’s goals: see ‘PISA 2018

Technical Report’, OECD website. For discussion of other countries’ trends

over time in PISA, see Andreas Schleicher, PISA

2018: Insights and Interpretations, (Paris: OECD, 2019), 11.

[60]. Thomson et al.,

PISA

in Brief 1, 7. The Measurement

Framework for Schooling in Australia identifies Level 3 on the PISA scales

as the national proficiency standard for 15-year old students as it represents a

‘challenging but reasonable’ expectation of student achievement a year level.

[61]. Linda Graham, ‘What

Does Exclusionary Discipline Do and Why Should it Only Ever Be Used as a Last Resort?’,

QUT Centre for Inclusive Education blog, 15 October 2020; Linda Graham, Callula

Killingly, Matilda Alexander and Sophie Wiggans, ‘Suspensions

in QLD State schools, 2016–2020: Overrepresentation, Intersectionality and Disproportionate

Risk’, The Australian Educational Researcher (2023); Linda Graham,

Callula Killingly, Kristin Laurens and Naomi Sweller, ‘Overrepresentation

of Indigenous Students in School Suspension, Exclusion, and Enrolment Cancellation

in Queensland: Is There a Case for Systemic Inclusive School Reform?’, The

Australian Educational Researcher (2022); Linda

Graham et al. ‘Suspensions

and Expulsions Could Set our most Vulnerable Kids on a Path to School Drop-out,

Drug Use and Crime’; State of New South Wales, Answers to Questions on

Notice, Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of

People with Disability, Hearing on 7 May 2021, NSW.999.0037.0001,

5; Sullivan et al., ‘Schools are

Unfairly Targeting Vulnerable Children with their Exclusionary Policies’.

[62]. Sullivan et al.,

‘Schools are Unfairly Targeting Vulnerable

Children with their Exclusionary Policies’.

[63]. Graham et al.,

‘Suspensions

in QLD State Schools, 2016–2020’.

[64]. Jennifer

Chandler, ‘Suspending

Suspension’, Impact, ACU blog, n.d.; Graham et al., ‘Suspensions

and Expulsions Could Set our Most Vulnerable Kids on a Path to School Drop-out,

Drug Use and Crime’.

[65]. Chandler, ‘Suspending

Suspension’.

[66]. Daniel Quin, ‘Levels

of Problem Behaviours and Risk and Protective Factors in Suspended and Non-suspended

Students’, Educational and Developmental Psychologist 36 (no. 1),

(July 2019): 8–15.

[67]. Andrew

Bacher-Hicks, Stephen Billings and David Deming, The

School to Prison Pipeline: Long-run Impacts of School Suspensions on Adult Crime,

Working Paper 26257, (Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2019).

[68]. Sheryl

Hemphill, David Broderick and Jessica Heerde, ‘Positive

Associations between School Suspension and Student Problem Behaviour: Recent

Australian Findings’, Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice,

no. 531, (Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology, 2017).

[69]. Jordan Baker, ‘New

School Rules Aim to Reduce Suspensions’, Sydney Morning Herald, 19

February 2022.

[70]. Brett Henebery,

‘Will

the Government’s New Student Behaviour Strategy Work?’, The Educator

Online, 1 March 2023; see also Baker, ‘New

School Rules Aim to Reduce Suspensions’.

[71]. Lucy Carroll, ‘Principals

Given New Powers’, Sydney Morning Herald, 24 August 2023.

[72]. Prue Car (NSW

Minister for Education and Early Learning), New

Student Behaviour Policy to Address Disruptive Classrooms Available from Next Term,

media release, 24 August 2023.

[73]. Rachel Perera

and Melissa Kay Diliberti, ‘What

Does the Research Say about How to Reduce Student Misbehavior in Schools’, Brookings

Institution research blog, 21 September 2023.

[74]. For example,

see Andrea Banks, ‘Why

Do Children Misbehave? Finding the Root Causes of Classroom Misbehaviour’, Insights

to Behavior (blog), 22 April 2020; Linda Graham et al., ‘The Hit and Miss of Dealing with Disruptive

Behaviour in Schools’, EduResearch Matters (blog), 9 June 2015;

Nancy Rappaport and Jessica Minahan, ‘Breaking the Behavior

Code’, Child Mind Institute, 8 February 2023; SA Department for Education,

‘Suspension

and Exclusion Information for Parents and Carers’, fact sheet.

[75]. Kate Griffiths

and Maddy Williams, Impact

of Mobile Digital Devices in Schools: Literature Review, (Sydney: Centre

for Education Statistics and Evaluation, 2018).

[76]. Bonnor et al., Structural

Failure, 10; Jonathon Sargeant, ‘Are

Australian Classrooms Really the Most Disruptive in the World? Not if You Look

at the Whole Picture’, The Conversation, 16 January 2019; Jonathon

Sargeant, ‘Prioritising

Student Voice: ‘Tween’ Children’s Perspectives on School Success’, Education

3–13 42, no. 2, (2014): 190–200.

[77]. Linda Graham et

al., ‘The Hit and Miss of Dealing

with Disruptive Behaviour in Schools’.

[78]. Linda Graham et

al.

[79]. Australian

Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL), Classroom

Management: Standards-aligned Evidence-based Approaches, Research

Spotlight, (Melbourne: AITSL, 2021).

[80]. Thomson and

Hillman, TALIS 2018, 17.

[81]. Thomson and

Hillman, 17–8.

[82]. Thomson and

Hillman, 18.

[83]. Thomson and

Hillman, 18.

[84]. Thomson and

Hillman, 18.

[85]. AITSL, Australian

Professional Standards for Teachers, (Melbourne: AITSL, 2011, revised

2018), 16.

[86]. Paige Cockburn,

‘NSW

Government to Appoint Chief Behaviour Advisor to Boost Respect in Schools’,

ABC News, 26 September 2022.

[87]. Lucy Carroll, ‘State

Hires Behaviour Advisor to Tackle Student Conduct’, Sydney Morning

Herald, 2 March 2023.

[88]. WA Department

of Education, Annual

Report 2022–23, (Perth: WA Department of Education, 2023), 37.

[89]. WA Department

of Education, Annual

Report 2022–23, 37.

[90]. WA Department

of Education, 37.

[91]. Tom Bennett, Creating

a Culture: How School Leaders can Optimise Behaviour, Independent

review of behaviour in schools, (London: Department for Education, 2017); Justine

Greening (Secretary of State), Letter

to T Bennett – Government Response to Creating a Culture, Department

for Education, 24 March 2017; Amy Skipp and Vicky Hopwood, Case

Studies of Behaviour Management Practices in Schools Rated Outstanding,

Department for Education, 2017.

[92]. Edward Timpson,

Timpson

Review of School Exclusion, (London: Department for Education, 2019), 5;

see also Department for Education, The

Timpson Review of School Exclusion: Government Response, (London: Department

for Education, 2019); Aaron Kulakiewicz, Robert Long and Nerys Roberts, The

Implementation of the Recommendations of the Timpson Review of School Exclusion,

Research briefing, House of Commons, 2021; Department for Education, ‘School Discipline and Exclusions’,

gov.uk website.

[93]. US Department

of Education, ‘The Federal

Role in Education’, US Department of Education website.

[94]. US Department

of Education, ‘The Federal

Role in Education’.

[95]. US Department

of Education, ‘About

ED’, US Department of Education website.

[96]. National Center

on Safe Supportive Learning Environments (NCSSLE), ‘About’, NCSSLE website.