Dr Hazel Ferguson, Social Policy

Key issue

COVID-19 created severe problems for education and training providers and students alike. Considerations for the new Parliament may include the recovery of international education, the structure of higher education funding, and priorities for vocational education and training reform.

What is tertiary education?

Tertiary education comprises 2 sectors:

- Vocational education and training (VET), which is provided by over

4,000 registered training

organisations (RTO). In

2020, a total of 3.9 million students were enrolled in nationally

recognised training, and approximately 1.3 million of these students were

government-funded.

- Higher education, which is provided by 189 registered higher education

providers, including 42 Australian universities. In

2020, 1.6 million students were enrolled in higher education courses,

predominantly at universities. Of

these, 880,379 were Commonwealth

supported students.

Tertiary enrolments include students studying for certificates,

diplomas, and degrees as set out in the Australian

Qualifications Framework, as well as VET programs and subjects not delivered as part of a qualification- most

commonly cardiopulmonary resuscitation and first aid courses.

In 2021–22 (pp. 150; 168),

the Australian Government invested an estimated $7.1 billion in VET, and $10.7

billion in higher education, not including student loans or competitive research grants, such as those

provided by the Australian Research Council (ARC).

The majority of Australian

Government recurrent funding for VET is distributed via intergovernmental

agreements with the states and territories. States and territories are responsible for VET delivery in their

own jurisdictions, and contributed

an additional $3.9 billion to the system in 2020. In contrast, the Australian Government is the

primary funder of grants to approved

higher education providers, apprentice

incentive payments to employers and apprentices, and student loans for VET and higher education (which are generally paid directly to the

provider, on behalf of the student).

Tertiary education

during the pandemic

Border closures and

the international education downturn

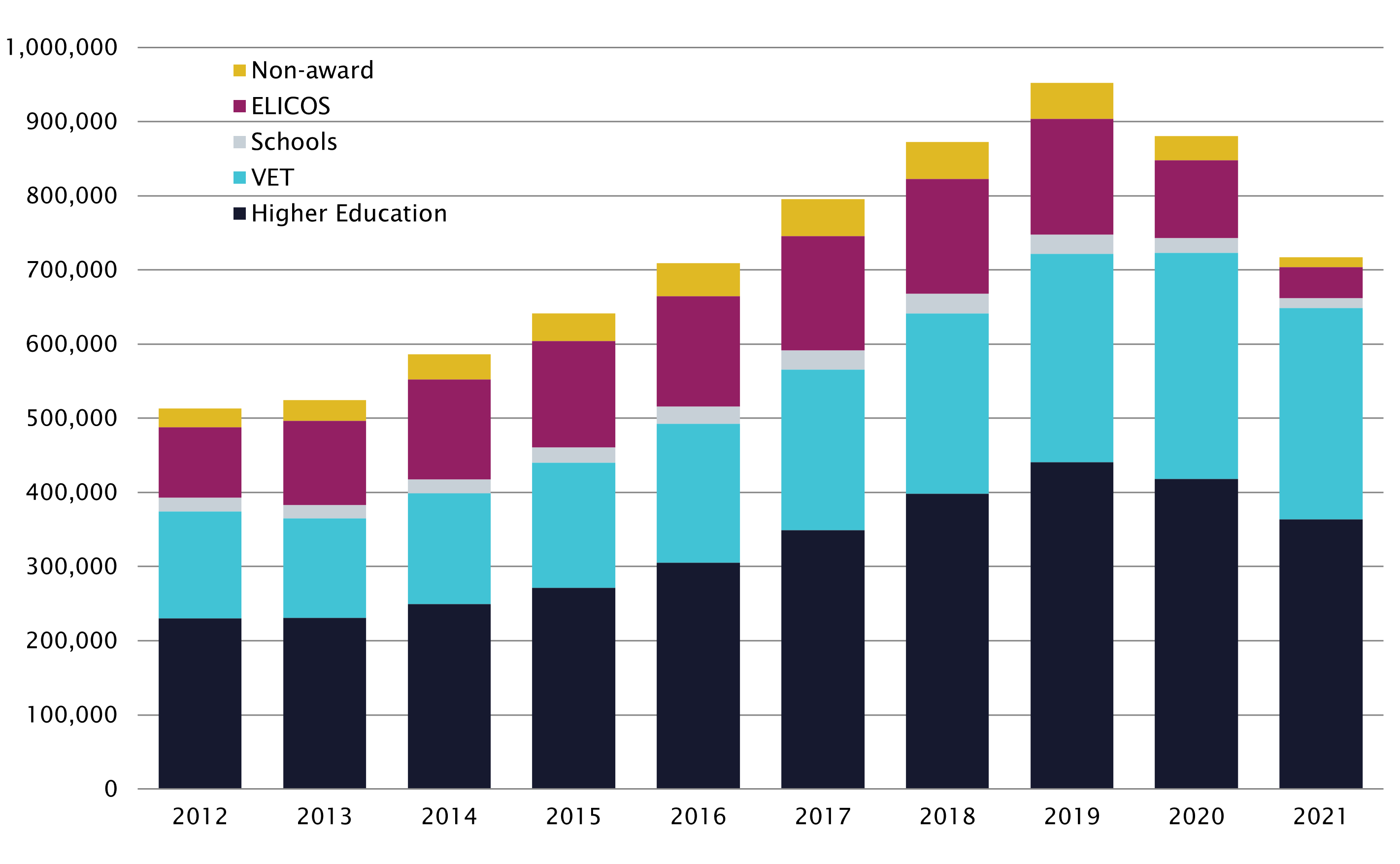

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic,

Australian education, particularly higher education, was increasingly

internationally engaged. Total overseas students studying in Australia had nearly

doubled between 2012 and 2019, from 513,083 to 952,163 (Figure 1), and by the

end of this period international students made up 32.4% of higher education students (and a smaller

proportion of other sectors, including 5.4% of VET students). International education constituted

a major services sector with strong year-on-year growth, worth $40.3 billion to the Australian economy in

the 2019 calendar year. In 2018, Australian universities reported participating in over 10,000

international agreements involving student and staff

exchange, academic and research collaboration, and other forms of mobility.

COVID-19 travel restrictions, beginning on 1 February 2020, and increasing on 20 March, had an immediate impact on student visa

holders, many of whom were outside the country when restrictions were

introduced. Despite a regulatory response

allowing students to continue studying from outside Australia,

many faced barriers to taking up this option, and instead deferred or cancelled

their studies (just over 25,000 more in the first quarter of 2020 compared with the

same period in 2019).

By the end of 2021, compared with the peak in 2019, total international

student numbers had declined by 24.7% to 716,921, primarily driven by falls in higher

education and English Language Intensive Courses for Overseas Students (ELICOS).

Enrolments from China, Australia’s largest source of overseas students, fell by

63,092 students (24.3%) between 2019 and 2021, while falling enrolments from

India (12,964 or 9.1%), Nepal (9,095 or 13.2%) and Brazil (18,940 or 46.5%)

were also substantial. In 2020, the economic contribution of international education was $31.7 billion, around three-quarters of its 2019

peak.

Figure 1 International education

enrolments by sector, 2012–2021

Source: Department of Education, Skills

and Employment (DESE), International

Student Monthly Summary and Data Tables (Canberra: extracted 17 May 2022).

In

November 2021, the Morrison Government released a ‘roadmap to recovery’ as part

of the Australian Strategy for

International Education 2021–2030, citing 2022

as the year international education is expected to regain ground. Under the strategy, a review of the Education Services for

Overseas Students (ESOS) Act and National Code of

Practice for Providers of Education and Training to Overseas Students 2018, which set out the

standards for Australian international education, was initiated. Measures were

also developed to diversify international

student cohorts and support online delivery for a sustainable

recovery.

In the first quarter of 2022, there

were some indications of recovery in the higher education sector. Commencement

data show 67,080 international students started a higher education course in

March 2022, compared with 61,171 in March 2021- a 9.7% increase. However, this

equates to only a 1.7% increase in total commencements, due to falls in ELICOS,

VET, and schools.

Enrolment data for the same period shows reductions

in total international student numbers across all sectors, and from all major

source countries. In part, this is due to the cumulative effect of lower

commencements in 2020 and 2021. The reduced number of students starting a

course during these 2 years now means lower than usual enrolments in the later

years of courses.

Higher education

For

higher education providers, the pandemic has

accelerated many trends that were already in progress, including online and

blended delivery, and the diversification of international student delivery to

include hybrid, online, offshore, and third-party arrangements.

Although students

experienced a range of challenges (p. 9) associated with learning during the pandemic, graduates

from this period have so far been, on the whole, well received by employers (p. 4).

The policy conversation has been largely dominated

by concerns about funding:

- In 2020, revenue from overseas student fees and investment income declined

due to the pandemic. Total sector revenue from overseas student fees decreased

by $755.8 million (7.6%), and investment income decreased by almost $1.2

billion (57.7%) in 2020, compared with 2019 (Table 1).

- Commencing in 2021, Australian Government funding and fees for

Commonwealth supported domestic students changed as part of the Job-Ready Graduates Package (JRG).

JRG included complex

changes to student and government contribution amounts, with the intent of

increasing enrolments in priority fields, while also reducing average Australian

Government per-student funding.

Table 1 University

revenue from continuing operations by source, 2019 and 2020

| Revenue |

2019 ($m) |

2020 ($m) |

Change ($m) |

Change (%) |

| Australian

Government |

17,782.6 |

18,186.3 |

403.7 |

2.3 |

| Grants |

11,976.4 |

12,122.3 |

145.9 |

1.2 |

| Student loans |

5,806.2 |

6,064.0 |

257.8 |

4.4 |

| State and local government |

725.4 |

763.7 |

38.4 |

5.3 |

| Upfront student contributions |

459.1 |

455.5 |

-3.5 |

-0.8 |

| Overseas student fees |

9,978.8 |

9,223.0 |

-755.8 |

-7.6 |

| Other fees and charges |

1,814.3 |

1,454.2 |

-360.1 |

-19.8 |

| Investment income |

2,191.3 |

927.4 |

-1,263.9 |

-57.7 |

| Royalties, trademarks and licenses |

136.1 |

139.6 |

3.5 |

2.5 |

| Consultancy and contracts |

1,567.8 |

1,628.8 |

61.0 |

3.9 |

| Other income |

1,863.9 |

1,872.6 |

8.6 |

0.5 |

| Total revenues |

36,519.2 |

34,651.1 |

-1,868.2 |

-5.1 |

Source: Parliamentary Library

calculations based on DESE, University finance data, (Canberra:

extracted 17 May 2022).

Notes: Student loans include HECS-HELP,

FEE-HELP, VET FEE-HELP, VET Student Loans, and SA-HELP. Other fees and charges

include: fee-paying domestic students, Student Services and Amenities Fee

payments, and other fees and charges. Other income includes donations and

bequests, non-government grants, and share of the net result (overall profit) of associates and joint ventures.

Many universities responded to financial pressures

by pursuing savings measures, especially staffing cuts. While there are a

number of challenges

in accurately estimating job losses, the Australian Government’s university

staff data collection indicates a reduction of 9,050 permanent

and fixed-term contracts in the 12 months to 31 March 2021, the majority in

non-academic roles. Casual staff losses began earlier. In

2020, in full-time equivalent (FTE) terms, 4,258 fewer casual staff were

employed than in 2019, a decline of 17.5%. Estimated

casual FTE figures for 2021 (which are the latest available, but provide

only a preliminary count) indicate a further decline of 3,641 (15.2%) in 2021

compared with 2020.

The latest higher

education research expenditure data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics reveals universities also reduced discretionary spending on research from

‘general university funds’ as income from international student fees fell.

Although overall expenditure increased slightly from $12.2 billion in 2018 to

$12.7 billion in 2020, contributions from general university funds fell slightly

from $6.8 billion (56.1% of total expenditure) to $6.7 billion (53.2% of total

expenditure), while funding from all other sources grew.

However, analysis

of university financial reports by the Melbourne Centre for the Study of Higher

Education suggests the financial impact of COVID-19 on universities was not

as significant as predicted early in the pandemic. The study acknowledges ‘severe

challenges to on-going financial sustainability’ but finds that universities

were ‘resourceful and resilient’ in 2020, with 8 institutions improving their

financial position, even while others experienced significant deterioration in

operating results.

Based on 2021 financial reports released to date,

universities have continued to report better-than-expected financial results,

including significant surpluses at the University of Sydney ($1.0 billion,

p. 44), Monash University ($410.6

million, p. 89) and theUniversity of Queensland ($341.9

million, p. 44). These results are largely driven by lower expenditure,

increased investment income, and the sharing of an additional one-off $1

billion in funding for university research in 2021 distributed among

universities by the Australian Government.

Skills training

VET policymaking in

2020 and 2021 was characterised by attempts to balance long-term reform

priorities with rapid responses to safeguard the domestic skills pipeline during

COVID-19.

Like in higher education, the

pandemic caused a rapid shift to online learning in VET. However, in early

2020, the apprenticeship system seemed the most at-risk part of VET, as

businesses closed or reduced staff. In

the June 2020 quarter, compared with the same period in 2019, total

apprentices in-training decreased 3.9% to 266,565. Larger falls were seen in commencements,

which dropped 35.8% to 21,115, and completions, which dropped 24.4% to 14,820.

New training was also rapidly developed and approved

in response to pandemic-specific skill needs. This

included new skill sets in infection control, digital skills, and

pharmaceutical manufacturing, to assist workers needing to upskill in response

to the health crisis, as well as those displaced by the economic effects of the

pandemic, and those whose work had moved online.

In response, 2 major Australian Government funding

sources were introduced to temporarily support the VET sector:

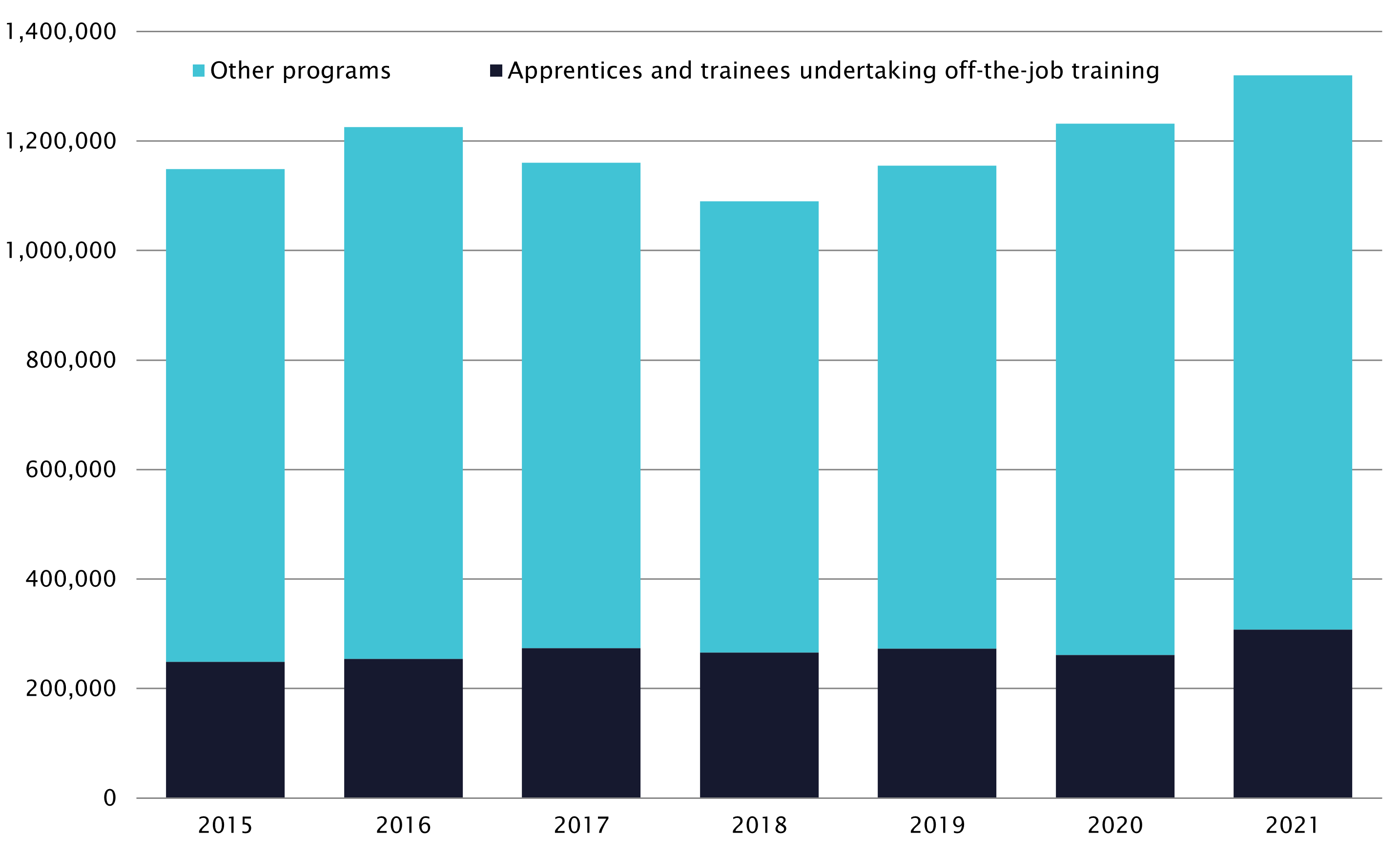

According to the latest program enrolment data to

September 2021, uptake of government-funded training, including courses taken

by apprentices, increased by 7.2% in 2021, compared with the same period in

2020, to 1.3 million (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Government-funded

program enrolments, January–September 2015–2021

Source: National

Centre for Vocational Education Research, VOCSTATS, (Adelaide:

extracted 30 May 2022).

However, the Morrison Government’s broader skills reform agenda was not realised

during the 46th Parliament. After a Heads

of Agreement for Skills Reform was finalised with the states and

territories in 2020 as a condition of access to JobTrainer funding,

jurisdictions did not reach agreement over the expected replacement for the National

Agreement for Skills and Workforce Development (NASWD).

The NASWD, which, according to a

review by the Productivity Commission in 2020, is ‘overdue for replacement’,

sets out jurisdictions’ shared responsibilities for VET, and is the basis for

approximately $1.6 billion of ongoing National Specific

Purpose Payments (SPP) from the

Australian Government, to support skills and workforce development each year (p. 45). The 2022–23

Budget allocated an additional $3.7

billion over 5 years from 2022–23 to work with states and territories on a replacement

for the NASWD.

In addition to funding provided through the skills

and workforce development SPP, the Australian Government also exercises

significant influence over the VET system as the funder of VET

Student Loans, Trade

Support Loans, and apprenticeship

incentives. Key bodies also operate under Commonwealth legislation: the National

Skills Commission (NSC) under the National Skills Commissioner Act 2020, and the national VET regulator, the Australian Skills Quality

Authority (ASQA), under the National Vocational

Education and Training Regulator Act 2011.

Three questions for

COVID-19 recovery

As tertiary education rebuilds following the shocks of 2020 and

2021, three considerations that the new Parliament may face are sustainable

international education recovery, the structure of higher education funding,

and priorities for VET reform. These are briefly discussed below.

What does sustainable international education recovery look like?

Although there are early signs of

recovery in demand for Australian higher education from overseas students, the long-term

impact of declining enrolments signals a need for careful management of

international education policy over the medium term.

This encompasses not only education policy, but also visa policy

(discussed in the 'Immigration' article elsewhere in this Briefing book). For

example, recent diversification efforts among providers, combined with the temporary removal of student visa conditions

related to work hours, are thought to have led to rapid increases in visa applications from prospective VET students

from Nepal.

The pandemic has increased attention on university reliance on revenue from international students, as

well as the responsibility of governments and providers to support students

through challenges during their time in Australia, which

were particularly marked during the early stages of the pandemic.

Australia is not alone in negotiating how to rebuild international education to

better meet the needs of students and education providers. For example, New Zealand’s draft new International education strategy has been described as ‘value over volume’.

Is the structure of

higher education funding fit for purpose?

Despite better-than-expected financial performance from

some universities in 2020 and 2021, several key questions related to the

structure of higher education funding remain.

Although Labor’s commitment to provide ‘up

to 20,000 new university places’ can be achieved under the current funding arrangements,

many policy analysts continue to express concerns about JRG that, if addressed,

would require larger-scale changes via the Higher Education

Support Act 2003. Concerns include that incentives

for students and universities to increase enrolments in priority courses will

be ineffective, and that the

increased gap between the highest and lowest student contribution amounts is

not justified.

There is also considerable uncertainty about the

future of research funding for universities. In addition to declining

investment capacity from general university funds and the end of the temporary

additional $1 billion provided in 2021, concerns

have been raised about the independence of the ARC. As well, the University

Research Commercialisation package announced in February 2022 by the Morrison

Government was not legislated despite the introduction of 2 Bills to give effect to different parts of the package.

Labor has signalled a broad reconsideration of

higher education policymaking through an Australian

universities accord: ‘a partnership between universities and staff, unions

and business, students and parents, and, ideally, Labor and Liberal- that lays

out what we expect from our universities.’ This approach has attracted early support from the sector, and may provide a ‘turning point for higher education in Australia’.

What are the priorities for VET reform?

Despite widespread

acknowledgement of the need for VET reform to meet specific

skill needs as well as the demands of increasingly higher

skill, non-routine and cognitive jobs that are not easily replicated by

machines (p. 146), recent efforts to renew the NASWD failed to balance the priorities

of governments, employers, unions, and the training and education sector. Skills ministers from 6 states and territories reportedly wrote to the Government in early 2022 expressing concern about the proposed new agreement, including potential

reductions in funding to TAFEs, and the proposed role of the NSC in setting prices

and subsidies.

Labor

has signalled a possible shift towards public providers, with a commitment

to direct at least 70% of Australian Government VET funding to TAFE and provide

fee-free TAFE places in priority fields. It has also flagged the creation of a

new body, Jobs

and Skills Australia: ‘an independent body to bring

together the business community, states and territories, unions, education

providers and regional organisations to match skills training with the evolving

demands of industry and strengthen workforce planning’. This body could incorporate much of the current work

of the NSC.

Further reading

Hazel Ferguson, Tertiary Education: a Quick Guide to Key Internet Links, Research paper series, 2020–21, (Canberra: Parliamentary Library, 2021).

Hazel Ferguson, A Guide to Australian Government Funding for Higher Education Learning and Teaching, Research paper series, 2020–21, (Canberra: Parliamentary Library, 2021).

Carol Ey, The Vocational Education and Training Sector: a Quick Guide, Research paper series, 2020–21, (Canberra: Parliamentary Library, 2021).

Hazel Ferguson and Harriet Spinks, Overseas Students in Australian Higher Education: a Quick Guide, Research paper series, 2020–21, (Canberra: Parliamentary Library, 2021).

Hazel Ferguson, University Research Funding: a Quick Guide, Research paper series, 2021–22, (Canberra: Parliamentary Library, 2022).

Back to Parliamentary Library Briefing Book

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.