Dr Emily Gibson, Science, Technology,

Environment and Resources

Key issue

Australia’s coasts and marine ecosystems are facing a range of threats, including climate change, coastal development, land-based run-off, and direct human uses.

Three major regulatory issues in Commonwealth waters are oil and gas exploration and production (including decommissioning), electricity infrastructure, and aquaculture.

Achieving a balance between competing uses and users will be crucial for achieving a sustainable ocean economy, consistent with Australia’s recent international policy commitments.

With the sixth

largest coastline and third

largest marine area in the world, the Australian coast and marine

environment is intimately

linked to the national economy, industry, arts, social lifestyle and cultural

identity. More than 85%

of Australians live within 50 kilometres of the sea.

The value of Australia’s coast and marine resources

is often referred to in economic terms. For example, the AIMS index of

marine industry 2020, which assesses

the contribution of Australia’s ‘blue economy’ to the nation’s economic bottom

line, estimates that the economic output of 14 marine industries was $81.2

billion in 2017–18. In addition, the coast and oceans provide an estimated $25 billion worth

of ecosystem services, such as carbon dioxide absorption, nutrient cycling,

and coastal protection. Other values cannot be easily

measured in economic terms: for example, the intrinsic recreational value of

the coast and ocean, and the cultural importance of Sea Country to Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Coastal ecosystems, including mangroves, seagrass

meadows and tidal marshes, and the ocean, play a critical role in the carbon

cycle. Coastal blue carbon ecosystems sequester

more carbon dioxide than terrestrial forests. Australia is considered a

‘blue carbon hotspot’, with 12%

of the world’s blue carbon ecosystems holding 7–12% of global carbon stocks.

The Australian Government is taking a range of measures to restore,

conserve and account for blue carbon ecosystems. Additionally, in January

2022, a blue

carbon method was approved under the Emissions Reduction Fund, allowing

projects that restore tidal flows in blue carbon ecosystems to generate

Australian Carbon Credit Units.

Australia is a member of several international organisations

which collectively seek to increase marine ecosystem protections and achieve a

sustainable ocean economy. The High Ambition Coalition for

Nature and People and Global

Ocean Alliance both aim to protect at least 30% of the world’s land and

oceans (in marine protected areas (MPA) or ‘other effective area-based

conservation measures’) by 2030. The High

Level Panel for Sustainable Ocean Economy (Oceans Panel) seeks to ensure

that 100%

of the ocean area under national jurisdiction is sustainably managed using sustainable ocean

plans by 2025.

Australia’s sustainable ocean plan is yet to be

developed. However, a range of other policy and planning instruments exist,

including Australia’s

oceans policy (1998), marine

bioregional plans prepared for 4 of the 6 Commonwealth marine regions (all

released in 2012), and 10–year management plans

for Commonwealth marine parks (all updated in 2018). The new Government has committed

to undertaking statutory reviews of marine park management plans (noting these

cover approximately 20% of Australia’s exclusive

economic zone) and making changes based on scientific evidence and

stakeholder consultation.

State of the coast and oceans

The 2016 State

of the environment report highlights the multiple

pressures impacting coastal and ocean systems and processes, operating at

different spatial and time scales. In 2021, researchers identified 5

coastal and marine ecosystems classified as ‘collapsing’: the Great Barrier

Reef (GBR), mangrove forests of northern Australia, Ningaloo Reef, Shark Bay

seagrass beds, and Great Southern Reef kelp forests. Stakeholders, including

the Australian

Marine Conservation Society, have expressed concern that the major parties

policies are inadequate to address key threats, including climate change and

land clearing.

The World

Heritage-listed GBR receives

significant investment from the Queensland and Australian Governments to

address threats

including climate change, coastal development, land-based run-off, and direct

human uses. Notably, in the summer

of 2021–22, the GBR experienced its fourth mass bleaching event since 2016- and

the first one during a La Niña year (which are typically associated with cooler ocean

temperatures).

However, the Great Southern Reef receives considerably

less attention and investment- despite encompassing 8,100 km of coastline from

Western Australia (WA) to NSW. The Great Southern Reef is

home to

diverse and unique species and incorporates the only marine ecological

community listed as endangered under the Environment Protection

and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act), the Giant

Kelp Marine Forests of South East Australia. The Great Southern Reef faces

similar threats to the GBR, compounded by ocean temperatures warming at 2–4

times the global average and range expansion of species, such as long-spined sea

urchins and tropical herbivorous fish that graze on and reduce cover provided

by kelp and seagrasses. Marine scientists and advocates- as well as the Australian Greens- are arguing for greater recognition of the Great Southern Reef

to support sustainable and adaptive management across relevant state and

Commonwealth jurisdictions.

Governance of the coast and oceans

Governance of Australia’s coasts and oceans is

shared in accordance with the Offshore Constitutional Settlement (OCS) by the Commonwealth, state and Northern Territory (NT)

governments. Local governments also play an important role with respect to

coastal zone planning and management.

The OCS, established in June 1979, provides that

the states and NT regulate activities in coastal

waters (from the territorial

sea baseline out to 3 nautical miles). The Commonwealth regulates

activities in offshore areas (those beyond 3 nautical miles, encompassing the exclusive

economic zone and Australian

Fishing Zone). The Commonwealth has entered into separate Joint

Authority arrangements with Queensland, WA and the NT to enable certain

fisheries that straddle coastal and offshore waters to be managed under state

legislation.

These arrangements coexist with Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander peoples’ traditional estates, which include land and

marine areas (often referred to as Sea Country). Indigenous customary and

subsistence fishing and other marine resource rights are recognised to some

extent in all Australian jurisdictions. Recent initiatives- including Aboriginal

Coastal Fishing Licences in the NT and the allocation

of abalone quota in Tasmania- are providing commercial opportunities. Sea

Country is also included in 25 of 78

Indigenous Protected Areas (IPAs), while over a quarter of the 126 Indigenous

ranger groups undertake a range of Sea Country management activities.

Indigenous ranger programs provide positive outcomes for employment, the environment, and Indigenous mental health, and the incoming Government has committed to expanding these programs.

Australia’s marine parks, including 2

recently declared Commonwealth marine parks in the Indian Ocean Territories,

cover

more than 4 million km2 or 45% of Australia’s waters. However, a

2021 study found that only

25% are fully protected (International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)

Category Ia and II). The previous

government oversaw a large-scale downgrading of marine protections when, in

2018, approximately 1 million km2 of the total MPA estate (31%) was

rezoned. Around half the downgraded MPAs were offset by increased protections

in other MPAs. Downgraded areas were opened up to

activities such as commercial fishing and oil and gas exploration under a

range of ‘class approvals’, prior usage rights, or licenses.

Regulatory issues in the blue economy

Offshore oil and gas, and greenhouse gas storage

The Offshore Petroleum

and Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2006 (OPGGS Act) is the

predominant framework regulating offshore oil and gas and greenhouse gas

storage activities. Oil and gas titles cover 392,278

km2 of the Commonwealth offshore area, predominantly to the

north-west of WA and in Bass Strait.

The National

Offshore Petroleum Titles Administrator (NOPTA) issues titles for offshore

oil and gas and greenhouse gas storage activities, on the advice of the

relevant Commonwealth–state/territory Joint Authority or,

in some circumstances, the Commonwealth Minister for Resources.

The National

Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority (NOPSEMA)

regulates offshore work health and safety, well integrity, and environmental

management. NOPSEMA’s environmental management authorisation process has been endorsed

in a strategic assessment under the EPBC Act. This means that petroleum exploration and production, and greenhouse gas

storage exploration (with limited exceptions) do not require separate approvals

under the EPBC Act.

The Department of Industry, Science, Energy and

Resources (DISER) releases new

areas for exploration each year, with provision for public consultation. In

2021, the department also released

areas for potential greenhouse gas storage opportunities, consistent with

the Morrison Government’s support

for carbon capture and storage (CCS).

There is considerable community

and stakeholder concern about offshore oil and gas projects. These concerns

include the provision of grants and other subsidies in light of the need to

decarbonise economic activity, potential for oil spills, impacts

of seismic testing on marine mammals and commercial fisheries, conflicts

with recreation activities, and visual impacts.

Following a sustained community-led

campaign, the Australian Government, as part of the Commonwealth–NSW

Joint-Authority, is

taking steps to refuse an application to extend a petroleum exploration permit

(known as PEP-11) for an area off the NSW central coast. There is also community

concern about on-going and proposed developments in the Great Australian

Bight and Bass Strait, including near the Twelve

Apostles (Vic) and King

Island (Tas). The Australian

Greens and some independent federal parliamentarians have advocated for a

moratorium or ban on new oil and gas developments.

The decommissioning of offshore oil and gas

infrastructure emerged as a significant issue during the 46th Parliament. Titleholders

have an ongoing

legal obligation to maintain all structures and equipment on their titles in

good repair and to decommission (that is, remove) all equipment and other

property as soon as it ceases being used or required for future use. However, this

has

not always occurred in a timely, safe and environmentally responsible manner,

with some

companies seeking permission to cap wells and leave associated equipment in

place. The decommissioning liability for Australia’s offshore petroleum

industry has been estimated at approximately

$60 billion over the next 50 years.

In February 2021, the

Government took over responsibility for the operation and decommissioning

of the Northern Endeavour Floating Production Storage and Offloading (FPSO)

facility following the financial collapse

of its owner. In April 2022, the Parliament passed legislation

imposing a temporary levy on offshore petroleum production licence holders to

recover the cost of decommissioning the Northern Endeavour. This has been estimated

at up to $1 billion.

Following a

review of the decommissioning framework, the Parliament passed amending

legislation in September 2021 to increase oversight of changes in control

of titleholders, and to expand existing powers to ‘call back’ previous

titleholders to decommission infrastructure and remediate the marine

environment where the current or immediate former titleholder is unable to do

so (known as ‘trailing liability’). At the direction

of the Australian Government, NOPSEMA is maintaining a heightened focus on

decommissioning, consistent with the Government’s enhanced

decommissioning framework.

Offshore electricity infrastructure

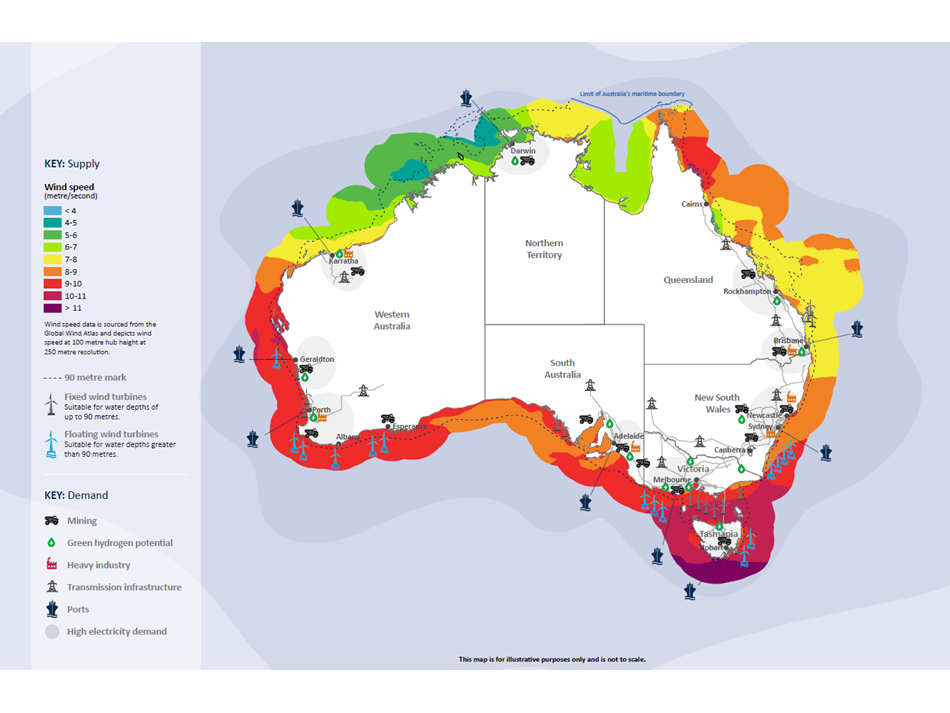

Australia is regarded as having some

of the best wind resources in the world, providing significant

opportunities as a bulk source of clean energy. The Blue Economy CRC

estimates the technical

offshore wind resource as 2,233 gigawatts (GW) – significantly more than Australia’s

current and projected electricity demand. While much of this resource is

located in the coastal regions stretching from WA to south-east Australia, there

are reported benefits

of co-locating offshore wind infrastructure near existing depreciating assets

(such as thermal coal power plants) and energy-intensive industries (see Figure

1).

Figure 1 Supply and demand potential for

offshore wind energy

Source: NOPSEMA,

May 2022.

To support offshore electricity infrastructure

development, the 46th Parliament passed the Offshore

Electricity Infrastructure Act 2021 (OEI Act) in December 2021;

the Act commenced on 2 June 2022. The OEI Act establishes a

regulatory framework and provides an expansive definition of offshore renewable

energy resources (wind, tidal, solar, rain, and geothermal, among others),

while offshore infrastructure includes fixed or tethered infrastructure for the

storage, transmission or conveyance of electricity.

The OEI Act allows the relevant minister to declare

areas as suitable for offshore renewable energy infrastructure, and to make

licensing decisions. In April 2022, the Morrison Government announced that Bass

Strait would be the first priority area assessed for offshore wind developments.

The Offshore Infrastructure Registrar provides

advice to the minister who makes licensing decisions. The Offshore

Infrastructure Regulator (designated as NOPSEMA) will oversee

health and safety, infrastructure integrity, environmental management, and

financial security for offshore infrastructure activities. Separate

environmental approvals will be required under the EPBC Act.

The operational arrangements of the framework will

be detailed in regulations, which underwent

consultation in early 2022.

Offshore aquaculture

The production value of Australia’s aquaculture sector is

forecast to exceed $2 billion in 2021–22 (more than wild-catch fisheries at $1.39 billion). This exceeds the 2017 National

aquaculture strategy’s projection for 2027. While over half of this value ($1.36 billion) is predicted to flow

from salmonids (salmon and trout) farming, other important species include rock

lobster, prawns, southern bluefin tuna, abalone and pearls. The Australian

seaweed industry blueprint also highlights opportunities for the

development of seaweed industries.

At present, aquaculture occurs

in land-based operations (for example, hatcheries) and in coastal waters,

regulated by the states and NT. However, offshore aquaculture is becoming more

feasible due to improvements in technology; it also offers potential

environmental and resource access benefits. A recent parliamentary report recommended

increased regulatory efficiency and transparency, including consistency across

jurisdictions, stronger biosecurity controls, and the development of

aquaculture in Commonwealth waters.

According to the National aquaculture strategy, the Australian Government supports using Commonwealth Fisheries Management Act 1991 (FMA Act) provisions to enable state and NT

governments to extend existing aquaculture legislation and management into Commonwealth

waters. Any activities likely to have a significant impact on a matter of national environmental significance will require approval under the EPBC Act.

However, assessments and approvals could potentially be delegated to states and

territories as part of bilateral agreements.

Australia’s first offshore

aquaculture project is likely to occur in Commonwealth waters north-east of

Tasmania. In September 2021, the Commonwealth and Tasmanian Governments entered

into a memorandum of understanding to allow a trial examining the economic,

environmental and operational feasibility of offshore aquaculture. The Tasmanian

Government amended the Living Marine Resources Management Act 1995 to allow for ‘marine farming of fish for research

purposes’. The subsequent Commonwealth and Tasmanian Government agreement allows

‘marine farming of fish for research purposes’ to be carried out in these

specified waters, managed under Tasmanian law.

In response to public

submissions, the trial area was reduced. Concerns

raised include potential negative impacts on the local ecology, biodiversity

and environment, animal welfare and habitat impacts, attraction of predators,

and conflicts with recreational activities and local fishing operators. This

follows long-standing environmental sustainability concerns

about salmonid aquaculture in Tasmania,

compounded by the mass salmon deaths in Macquarie Harbour during 2017–18.

The trial may provide a template for future aquaculture development

in Commonwealth waters. However,

devolved Commonwealth regulatory powers are unlikely to provide consistency

across all facets of aquaculture, especially relating to licence and lease arrangements.

Further reading

Blue Economy CRC, Offshore Wind Energy in Australia, Final project report, 2021.

Leah Ferris and Liz Kenny, Offshore Electricity Infrastructure Bill 2021 [and] Offshore Electricity Infrastructure (Regulatory Levies) Bill 2021, Bills Digest, 27, 2021–22,

(Canberra,: Parliamentary Library, 21 October 2021).

Emily Gibson, Offshore Petroleum (Laminaria and Corallina Decommissioning Cost Recovery Levy) Bill 2021 [and] Treasury Laws Amendment (Laminaria and Corallina Decommissioning Cost Recovery Levy) Bill 2021, Bills Digest, 32, 2021–22, (Canberra: Parliamentary Library, 19 November 2021).

K Roberts, O Hill and C Cook, ‘Evaluating Perceptions of Marine Protection in Australia: Does Policy Match Public Expectation?’, Marine Policy, 2020, 112, e103766.

Back to Parliamentary Library Briefing Book

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.