Elliott King, Economic Policy, and Dr

Matthew Thomas, Social Policy

Key issue

Access to affordable and safe housing is essential to people’s health and wellbeing. Housing also forms a significant part of the economy. It is central to economic participation and productivity and a source of investment and wealth creation.

There is insufficient affordable housing to meet demand in Australia.

Housing affordability is a perennial issue in Australian politics. Various policies have been implemented to directly address affordability, though this usually takes the form of house purchase assistance or rental assistance (‘demand side’ measures).

Ideally, government interventions in the housing market should consider their impact across the entire housing continuum and be delivered in a more coordinated manner that increases the likelihood of realising optimum outcomes.

The housing continuum

The housing system is comprised of numerous housing

markets, housing stakeholders and policy tools. Moreover, there is not a singular

type of housing or housing tenure. Policies attempting to influence one type of

housing or tenure type can have flow on effects

across the full continuum of housing.

The housing continuum can be thought of as the

spectrum of housing types and tenures. The main forms of

housing tenure in Australia are public housing, community housing, private

rental and home ownership. Figure 1 illustrates a continuum, within which

different stakeholder groups and policy options could be listed to understand

where marginal changes to policy can impact across the entire system of housing

supply.

Figure 1 A housing continuum

Source: Adapted from Australian Government, Affordable Housing Working Group: Issues Paper,

prepared for the Council on Federal Financial Relations, (Canberra: Department

of Treasury, 2016), 2.

Any approach that is developed to address the needs

of a particular group – such as people with disability, first home buyers,

rental distressed, or key workers – can be located in this continuum. However,

pulling one policy lever may affect the entire continuum, having both direct

and indirect consequences in the wider housing market. A

well-functioning housing continuum would be in balance and necessary

interventions would ensure there are appropriate homes and supports at all

points to meet the needs of the community.

The participants in the housing spectrum are

diverse, including all layers of government, the individuals in need of housing

(public and private renters, and owner-occupiers), non-government providers,

public housing authorities, government funding bodies, private financiers and

property developers. Often, the delivery of housing stock and supports involves

explicit or implicit partnerships between these stakeholders (see, for

example, the NSW Government’s Landcom).

Insights: challenges across Australia’s housing continuum

Housing affordability has been an issue for some

time, however the latest cause of housing affordability concern stems from rapid

house price increases in capital cities and regional centres since the

onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

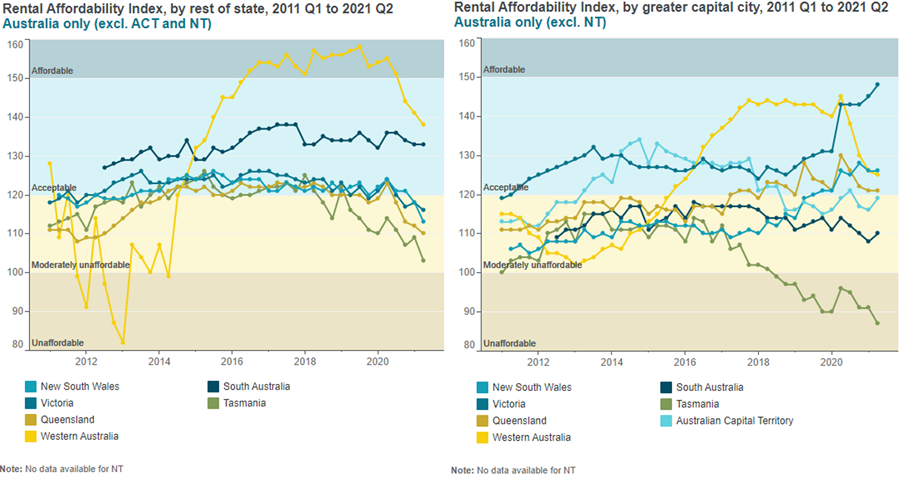

The effect of these increases is not only

experienced by home purchasers but has also manifested in higher rents – in

most regions – for those in the rental market. Figure 2 shows the fluctuations

in the SGS

Economics’ Rental affordability index since 2011. Notably, rental

affordability appears to have worsened in most regions during the pandemic

despite rental moratoriums being in effect in most jurisdictions throughout

2020.

Figure 2 Rental affordability in

capital city regions and ‘rest of state’ to Q2 2021

Source: Australian Institute of Health and

Welfare (AIHW), Housing Data

Dashboard, Rental Market: Rental Affordability Index Tables, (Canberra:

AIHW, 2021).

Deteriorating rental affordability impacts a large

and growing proportion of households. Table 1 shows the proportion of

households in some form of rental accommodation in 2019–20. The proportion of

households in the rental market now, compared to 1994–95 has risen from about 26%

to 31% of households. Notably, the average proportion of household income to

housing costs has not changed substantially between these periods, but

examination of disposable income by quintile reveals that those in the lowest

quintile have seen an increase in their housing costs relative to household

income over this period, rising from an average of 22% to 29% (ABS, Housing

occupancy and costs, (Canberra: ABS, 2022), Table 1.2).

Table 1 Proportion of households that are owner

occupiers compared with private and public renters, and

proportional housing costs

| Owners

and renters |

1994–95 % |

Housing

costs as a percentage of household income 1994-95 |

2019–20 % |

Housing

costs as a percentage of household income 2019-20 |

| Owner

without a mortgage |

41.8 |

3.1 |

29.5 |

3.0 |

| Owner with a

mortgage |

29.6 |

18.4 |

36.8 |

15.5 |

| State or

territory housing authority renters |

5.5 |

17.5 |

2.9 |

19.5 |

| Private

landlord |

18.4 |

20.1 |

26.2 |

20.2 |

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics

(ABS), Housing

Occupancy and Costs 2019- 20, (Canberra: ABS, 2022).

Note: The table only includes the main

categories of renters—private and public housing renters. It does not include

renters in community housing.

Additionally, mortgage

stress (usually defined as 30% or greater of pre-tax income allocated to

mortgage repayments, though there

is some nuance to this calculation) is reportedly

worsening in the face of recent interest rate increases. The latest authorised deposit-taking institution quarterly statistics

show that although high loan-to-value ratio (LVR) (that is, greater than 90%)

loans have declined, new residential mortgage loans with a debt-to-income (DTI)

ratio greater than 6 increased from 17% of new loans to 24% between December

2020 and December 2021. In a period of rising interest rates, having a higher

DTI or high LVR – and so higher repayments relative to income – makes it more

likely that a borrower who experiences an adverse shock to their income or

expenses will miss mortgage repayments. The Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA)

April 2022 Financial stability review examines the risk these

borrowers pose to the stability of the financial system, but also includes

analysis of mortgage stress for high-DTI and high-LVR loans. Although these

loans account for a small proportion of overall lending, they have

‘historically been around four times more likely to report mortgage stress than

other borrowers, and three times more than those with only a high DTI or a high

LVR’.

The state of Australia’s social housing supply

Social housing is housing made available at below

market rates to low-income households that are unable to afford or access

suitable accommodation in the private rental market. It comprises public

housing, community housing, state-owned and managed Indigenous housing (SOMIH),

and Indigenous community housing. Public housing is owned and managed by state

and territory governments, while community housing is either owned or managed

by not-for-profit community sector organisations.

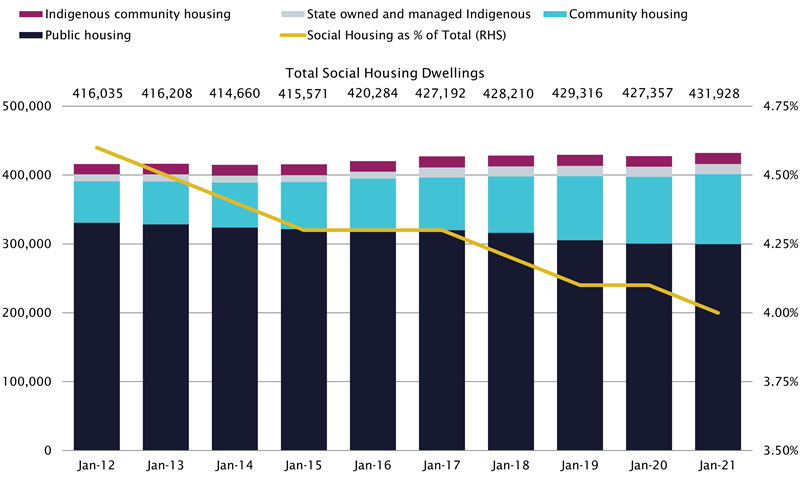

There are a range of measures for calculating

changes in the level of social housing. Social housing stock may be considered

as a percentage of overall housing stock or in relation to the size of the national

population. It is also possible to gauge the number of social housing

households as a proportion of total Australian households. Irrespective of the

measure used, it is evident that Australia’s social housing stock has been

declining for some time (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Social housing stock as

a proportion of total housing stock

Source: Productivity Commission, Report on Government Services 2022,

Housing and Homelessness, (Canberra: Productivity Commission, 2022)

Current social housing

stock is insufficient to meet present and projected need. As

at June 2021 there were 163,508 applicants on waiting

lists for public rental housing and more than 40% (67,656) of these were new

greatest need households– that is, households that were homeless, in inappropriate

housing that did not meet needs, adversely affected health or placed life and

safety at risk; or households that had very high rental costs. Additionally, almost

60% of applicants for mainstream community housing were in greatest need

(27,642 households) and 54% of the applicants awaiting SOMIH housing were in

greatest need (4,018 households).

Waiting list data may

overstate the level of need for social housing because some applicants may be

on more than one wait-list. Nevertheless, if the ‘evident need’ for social

housing is considered, then waiting list data may be seen to significantly underestimate

the real need for social housing.

Evident need typically

refers to households that are on a low income (approximately the bottom

quintile for the relevant household type) and in rental stress (in private

rental and paying more than 30% of income on rent). While these households may

be eligible for social housing, they may not apply for a number of reasons,

such as the stigma attached to this form of housing or because they are

discouraged by lengthy waiting times.

Government intervention in housing in general

Contemplating housing as a continuum reveals a

range of policy choices for governments at all levels. Broadly

speaking, the roles of Australian governments with regard to housing are:

- the federal government is responsible for national housing and

homelessness policy, financial sector regulations and taxation settings, which have

some influence on housing affordability

- state and territory governments are responsible for land use and

supply policy, urban planning and development policy, housing-related taxes and

residential tenancy legislation and regulation, each of which has an impact on

housing affordability

- local governments are mostly responsible for building approval,

urban planning and development approval processes, and rates and charges.

Table 2 presents a summary of specific types of

housing market interventions by level of government. As may be apparent,

certain policy levers – particularly at the federal level – are not specific to

housing provision but can significantly impact on encouraging or discouraging

the expansion of housing.

Table 2 High-level overview of

housing market interventions by level of government

| Government level |

Supply |

Demand |

| Encourage |

Discourage |

Encourage |

Discourage |

| Australian |

Monetary

policy (interest rates)

Major

infrastructure

State

and local government grants (eg GST, roads)

Regional

development support (RDA, City Deals, Smart Cities)

Tax

exemptions or subsidies for dwellings |

Prudential

regulation (restrictive)

Environmental

protection and biodiversity conservation

Business

regulation |

Tax

incentives (income, company or capital)

Income

support

Subsidies

(NDIS and rent)

Crisis

or trauma categorisation

Employment

policy |

Austerity

measures

Constraints

on payments

User

fees

Red

tape |

| State

or territory |

Development

partnerships

Major

or moderate infrastructure

Transport

policy settings

Land

supply (green or brown field)

Grants

for targeted development

Land

use planning

Good

trades training |

Development

deadlines

Building

quality regime

Restrictions

on brownfield

Landholder

stamp duty

Value

capture(a)

Heritage

restrictions

Social

restrictions (eg affordable housing)

Planning

system (zoning, rules) |

Home

buyer incentives

Contiguous

support for targeted group

Social

infrastructure

Green

living or energy incentives

Public

housing

Community

housing supports

Targeted

zoning |

Land

tax

Conveyance

duty

Land

based levies

Tenancy

rules

User

fees and charges |

| Local |

Development

approval (speed)

Local

infrastructure

Urban

partnerships

Master

planning

Asset

management plans |

Development

controls, fees and charges

Rules

and regulations (transparency)

Betterment

taxes

Restrictive

environmental protections

Developer

contributions

Heritage

restrictions |

Place-based

development and planning approach

Community

assets

Green

living incentives |

General

rates

User

fees and charges |

(a) Where government recovers some or all

of the value which public infrastructure generates for private landowners.

Source: Hal Pawson, Vivienne Milligan and

Judith Yate, Housing Policy in Australia: A Case for System Reform, (gateway

East: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020); Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet

(PMC), Reform

of the Federation White Paper: Roles and responsibilities in housing and

homelessness, issues paper 2, (Canberra: PMC, 2014).

In recent years work has been put into bringing

institutions and private sector participants – banks,

superannuation

funds, and

similar – into the affordable housing supply system. But, there needs to be

greater coordination across all levels of government as the policy levers for

each point of the housing continuum are dispersed. Changes at one level of

government do not necessarily have the desired flow-on effects if corresponding

changes are not followed at other levels, or if another layer embarks on changes

without regard for actions taken elsewhere in the system. For example, local

governments may be focussed on maintaining the amenities of their specific

area, while the state or federal governments may be attempting to reshape the

entire urban environment to achieve a particular economic outcome.

How does the Australian Government currently

intervene in the housing system?

The federal government has no specific head of

constitutional power to legislate with respect to housing, which is the primary

responsibility of state and territory governments. Some housing

experts have argued that because federal and state roles and

responsibilities ‘cannot be robustly defined and allocated’, this complicates

housing policy-making, negotiation and accountability (p. 394).

Direct interventions

Irrespective of this limitation, the Australian Government

intervenes in the housing continuum in numerous ways. Most of the interventions

at the federal level focus on the demand side of the housing market. Table 3

sets out current direct interventions in the housing market.

Table 3 Australian Government direct

interventions in the housing market

| Intervention |

Targets |

Continuum point |

What is it? |

| First Home Super Saver Scheme (FHSSS) |

First home buyers |

Home buyers |

Assists first home buyers to build a deposit inside their

superannuation, to save for their first home, due to the concessional tax

treatment and higher rate of earnings realised. Individuals have been able to

make contributions since 1 July 2017 and apply to release their savings since

1 July 2018. |

| First Home

Guarantee Scheme (FHG) |

Primarily targeted at first home buyers, but

certain subprograms assist other cohorts |

Home buyers |

Deposit

guarantee scheme that provides a

guarantee on eligible loans equal to the difference between a deposit of at

least 5% and up to 20% of the property purchase price (to a maximum value, specified by area).

Certain subprograms set the minimum deposit requirement at 2%. |

| Managed

investment trusts (MIT) |

Investors |

Private renters |

An increase to the capital gains tax (CGT) discount for resident

individuals from 50% to 60% where the MIT has used residential real estate to

provide affordable housing for at least 3 years prior to sale; and for

non-resident investors, a 15%- withholding tax rate if the MIT has used the

residential real estate to provide affordable housing for at least 10 years. |

| Commonwealth

Rent Assistance |

A person or family that qualifies for an eligible social security

payment |

Private renters |

A non-taxable income supplement, paid fortnightly to eligible

recipients. The payment is 75 cents for every dollar above a minimum

rental threshold until a maximum rate is reached. The thresholds and rates

vary depending on the household or family situation., |

| Specialist

Disability Accommodation (SDA) |

For eligible participants in the National

Disability Insurance Scheme |

Public, community, private rental and ownership |

The NDIS funds SDA for a small number of NDIS participants with

extreme functional impairment, or very high support needs, when deemed

necessary and reasonable. SDA funding is used to stimulate investment in the

building of new dwellings for NDIS participants. |

| Foreign

investment (restrictions) |

Foreign investors |

Home buyers |

Generally, foreign investors must seek Foreign Investment

Review Board approval before acquiring residential property. Foreign

investors are barred from acquiring existing dwellings, except where the

investor is redeveloping an established dwelling in a way that ‘will genuinely

increase Australia’s housing stock’ (p. 15). |

| National

Housing and Homelessness Agreement (NHHA) |

State and territory governments |

Crisis housing and social housing |

The Australian Government provides funding to the states and

territories for the provision of social and community housing services,

crisis housing and homelessness services. |

| Affordable

Housing Bond Aggregator (AHBA) |

Social housing providers |

Community housing |

The AHBA is operated by the National Housing Finance and Investment

Corporation (NHFIC). AHBA

‘provides low cost, long-term loans to registered

community housing providers (CHPs) to support

the provision of more social and affordable housing’. |

Coordination mechanism

In the direct interventions, one special case is

the relationship established under various Commonwealth-state

housing agreements (currently

the NHHA).

The Commonwealth-State

Housing Agreement (CSHA) was the first national housing agreement and a

precursor to the NHHA. The first CSHA was driven largely by the need to address

a serious nation-wide housing shortfall after the Second World War. It

allocated funds for the construction of new rental dwellings only, with half of

this housing reserved for ex-defence force personnel. The intention was that the

federal government would support the states to deliver public housing to those

who wanted it, but with priority to those in greatest need.

Housing researcher,

Patrick Troy, notes ‘the Commonwealth was not setting out to replace private

ownership of dwellings but wanted to provide security of tenure and choice to

those who did not want or who could not afford to own a dwelling’.[1]

Over time the Australian

Government's focus has shifted to prioritising support for home ownership and

eligible renters in the private rental market. With this shift, social housing

has moved from being a palatable alternative tenure type to residualised

and increasingly stretched welfare

housing.

Indirect intervention

Indirect interventions may also occur, such as

through infrastructure development, lending standards and taxation settings.

Infrastructure contributions through City

Deals and Regional

Deals typically involve measures for property development, including social

housing (for example, the Hobart

City Deal includes construction of ‘affordable housing options’). These are

in addition to the Infrastructure Investment Program that impacts housing by altering the built environment.

The Australian Government can also influence the

housing market through the regulation of the financial services sector, macroprudential

regulation and taxation settings. For instance:

- Lending

standards (for example, LVR) and serviceability

requirements set by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority influence

credit availability for prospective home purchasers

- Negative

gearing allows an investor to offset housing associated expenses, including

loan interest payments and other outlays against their gross income, where the

income derived from the investment is exceeded by these costs.

- A 50%

discount on capital

gains tax (CGT) exists for Australian individuals who own an asset for 12 months

or more. A residential property that is a main

residence is fully exempt, provided eligibility and other assessment

criteria are met.

Although not directly under the control of the federal

government, the RBA targets a level in the cash rate, which

influences housing loan interest rates charged by financial institutions.

What can the federal government do to address

housing issues?

The mix of direct and indirect measures highlights

the complexity of the Australian Government’s involvement in housing. Direct

interventions have a clear effect, such as the FHG bringing forward home

purchases for eligible participants. Indirect interventions have wider impacts

than just housing; for example, tax changes to negative gearing or the CGT may

impact on investment decisions and tax arrangements more broadly.

A particularly vexing aspect of housing policy is

its long-term nature, and the effective locking-in of decisions as dwellings

are constructed. The work of housing policy experts, Hal

Pawson, Vivienne Mulligan and Judith Yates, suggests that the long-term

nature of this policy area requires:

- a broader and more equitable conception of

strategic housing policy – that is focused on delivering sufficient housing to

meet needs at all points of the continuum

- a research capacity that would support housing

strategy across the continuum – that is, enable the monitoring, analysis and

interpretation of housing system issues to assist in policy responses

- agreement on the roles and responsibilities of

all levels of government with regard to housing assistance

- a greater degree of policy and administrative

stability at the federal level.

Similar recommendations have been echoed in research reports

by the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, and previous parliamentary

inquiries.

With regard to social

housing, a group of prominent Australian housing researchers has

estimated that as at 2016 around 9% of all Australian households

were in need of social or affordable housing – that is, they were homeless, on

social housing waiting lists, or were low income households renting in the

private rental market and experiencing housing stress. This estimate translates

to a social housing need backlog of over 430,000 dwellings (p. 63). Based on

the assumption that the proportion of households in need of social housing

would hold constant over the next 20 years (but vary by region) it was

estimated that about 730,000 additional social housing dwellings would be

required to eliminate unmet need by 2036 (p. 1).

To prevent the existing

shortfall from worsening would

require the construction of nearly 15,000 additional

social housing dwellings a year. If the current backlog is to be eliminated,

the rate of construction would need to be around 36,000 dwellings a year. The

current annual social housing construction rate has been estimated

at just over 3,000 dwellings.

In the short-term, the Productivity Commission is currently

reviewing the NHHA- with its report due to the Treasurer by 31 August 2022.

This report will likely frame negotiations of the NHHA, which is due to expire

on 31 June 2023. Additionally, the House of Representatives Standing

Committee on Tax and Revenue tabled its final report into housing affordability in March

2022. This report did not receive a response from the Government prior to the 2022

federal election.

Further reading

Terry Burke, Christine Nygaard and Liss Ralston, Australian Home Ownership: Past Reflections, Future Directions, AHURI Final Report no. 328, (Melbourne: Australian Housing Urban Research Institute, 2020).

National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation (NHFIC), State of the Nation's Housing 2021- 22, (Canberra: NHFIC, 2022).

House of Representatives Standing Committee on Tax and Revenue, The Australian Dream: Inquiry into Housing Affordability and Supply in Australia, (Canberra: House of Representatives, 2022)

Productivity Commission, Report on Government Services 2022, Housing and omelessness, (Canberra: Productivity Commission, 2022).

[1]

Patrick Troy, Accommodating Australians: Commonwealth government

Involvement in housing (Sydney: The Federation Press, 2012), 283.

Back to Parliamentary Library Briefing Book

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.