Dr Matthew Thomas, Social Policy and

Penny Vandenbroek, Statistics and Mapping

Key issues

Australia is lagging behind most other OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries in terms of employment of people with disability.

The Disability Employment Services program, which assists people with disability to find and retain employment, is due to end in 2023, and the Department of Social Services is currently working on a replacement model.

People with disability

The United Nations Convention

on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities defines people

with disability as including those having ‘long-term physical, mental,

intellectual or sensory impairments’ which may act as a barrier to a person’s

full, effective and equal participation in society. The convention outlines the

ways in which the principles of full involvement can be achieved, including

through inclusive communication, universal design, reasonable accommodation and

by alleviating discrimination. Australia formally ratified

this convention on 17 July 2008. Addressing this

commitment from the domain of labour force participation, this article explores the employment outcomes for working age

(15 to 64 years) people with disability.

How are rates of disability

measured?

The Australian Bureau of

Statistics (ABS) measures disability based on a suite of extensive survey questions.

Participants are asked whether they have any conditions that have lasted, or

are expected to last, 6 months or longer. Whether these conditions limit,

restrict or impair the person’s involvement in a range of everyday activities

(for example, using public transport, communicating or walking 200 metres) is

used to assess core activity disability- from mild to severe. People with disability

are also assessed as to whether they have a schooling or employment restriction,

or some other non-specified impairment.

The term ‘disability’ is

used here to capture a range of impairments, activity

limitations and participation restrictions. Reported disabilities from key ABS surveys,

such as Disability,

ageing and carers, can be broadly

categorised as: sensory (hearing, vision, speech); intellectual; physical; psychosocial

(mental illness, memory problems, social or behavioural difficulties); head

injury, stroke or acquired brain injury; or other (a long-term condition that

requires medication or treatment and restricts daily activities).

In 2018,

Australians with disability constituted 13% of the working age population. This

estimate was about 18% when extended to the total population. From 65 years

onwards, the prevalence of disability increases; however, this is also a time

when the level of employment decreases considerably and people may become eligible for the Age Pension.

Labour force status

The labour force consists of the

employed (paid work of one hour or more per week) and the unemployed (not in

paid work, actively seeking work and available to work). The participation rate

expresses the labour force as a proportion of the relevant population, in this

case working age. In

2018, the participation rates for people with disability

ranged from 27% for people with profound or severe disability to 59% for people

with mild disability. In contrast, people with no disability had a participation

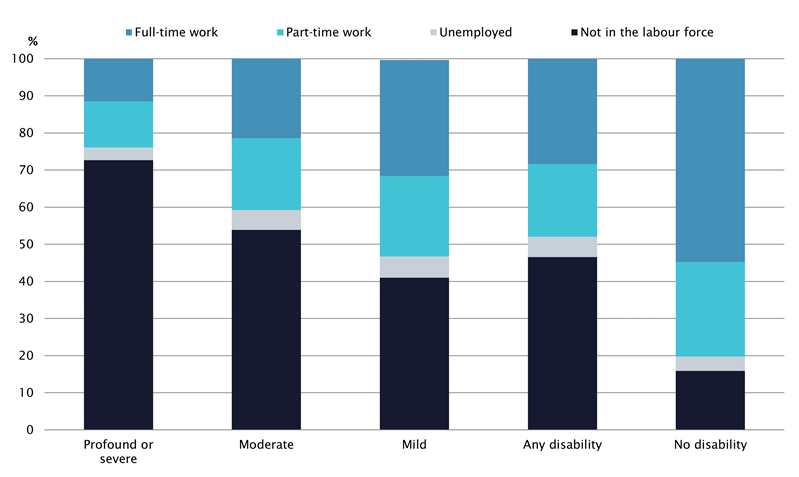

rate of 84%. Figure 1 helps to illustrate that people with any level of disability

are less likely to be in the labour force than those without.

Figure 1 People (15 to 64 years) by level of

disability and labour force status, 2018

Source:

ABS, Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia, 2018 (Canberra: ABS, 2019), Table

8.1; Parliamentary Library calculations.

Employment

The rates of employment among

people with disability vary based on their level of disability. In 2018, just over 2-in-10 people with profound or severe disability

were employed. While the employment rate was higher for people with moderate disability

(4-in-10 people), or mild disability (5-in-10 people), all of these rates were

lower than for people with no disability (8-in-10 people). In most

circumstances, people with disability are more likely to be employed part-time

than full-time.

Just

under half (48%) of people with any disability were employed in 2018, with variation in employment rates by type of

disability. The ABS organises types of disabilities into 5 broad groups:

- sensory and speech

- intellectual

- physical restriction

- psychosocial

- head injury, stroke or acquired brain

injury.

Within each of these groups

there may be a range of disabilities and employment outcomes. For example, 35%

of people with sensory and speech disability work full-time and 16% work

part-time (about 50% are employed). Employment rates within this group are

lowest for people with loss of speech (26%) and highest for people with loss of

hearing (59%), while rates for those with loss of sight are in between (43%).

People with physical

disabilities had the second highest employment rates (at 44%) of the broad

disability groups. However, within this group there was variation in the rates

by disability type, from 23% of people with breathing difficulties to 45% of

people with disfigurement or deformity. People with intellectual disability and

those with a head injury, stroke or acquired brain injury had comparable

employment outcomes, with less than a third of each group being employed (32%

and 29% respectively).

Of the 5 broad groups,

people with psychosocial disability were least likely to be employed, with only

a quarter (26%) in employment. People with mental illness had the lowest

employment rate (13%), followed by people with social or behavioural

difficulties (16%) and those with memory problems (17%). Of this disability

group, people with a nervous or emotional condition were most likely to be

employed (26%).

International employment rate comparisons

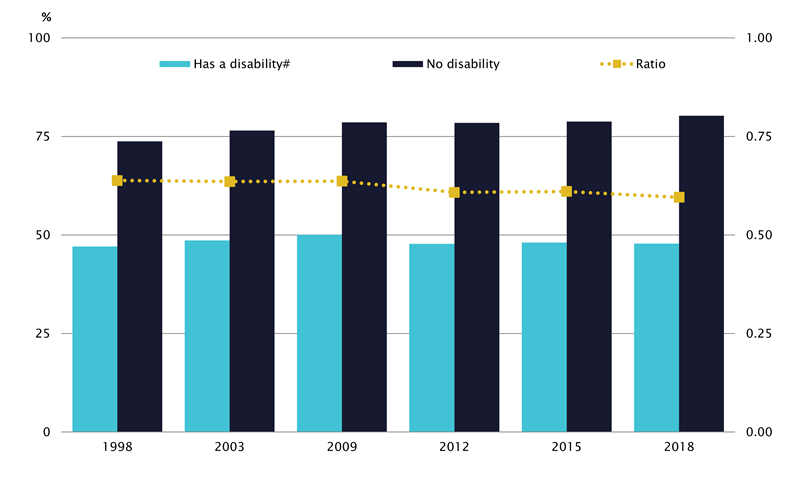

In 2017, Australia’s

employment rate gap between people with and without disability ranked 20th in the OECD (exhibit 2, p. 21). This was a slight improvement

from 2010 when Australia ranked 21st in the OECD (p. 40). Figure 2 provides the ratio of Australian

employment rates by disability status. The ratio is calculated by dividing the

rate for people with any disability by the rate for people with no disability.

Figure 2 Employment rates of people by

disability status (left axis) and ratio of employment rates (right axis), 1998

to 2018

(a) People

who reported any type of disability, includes those with a non-specified

restriction or limitation.

Source: ABS, Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia, various

years (Canberra: ABS, various);

Parliamentary Library calculations.

Disability employment

services

In Australia, the federal

government is responsible for providing employment services and income support for

people with disability. The employment services may be broadly divided into 2 main

categories:

- open employment services that provide

assistance to people with disability in gaining and/or retaining paid

employment in the open labour market

- supported employment services that provide

support to, and employment for, people with disability within the same

organisation.

Open employment services

are provided to people with disability through Australia’s mainstream

employment services program- jobactive- and the specialist Disability Employment Services (DES) program.

When a job seeker

registers for employment assistance, they complete a questionnaire- the Job Seeker Classification Instrument (JSCI). The JSCI is used to establish a job seeker’s

barriers to employment. If the job seeker is found to have a disability, they

may be referred for further assessment (either an Employment Services Assessment or Job Capacity Assessment). These assessments are used to determine a job

seeker’s work capacity in hour bandwidths and whether jobactive services

or DES are more appropriate to support them into employment.

The jobactive program

is administered by the Department of Education, Skills and Employment and the

DES program is managed by the Department of Social Services. Both jobactive

and DES have been privatised and contracted out to non-government for-profit

and not-for-profit providers.

The DES program

Two types of employment

support are provided to people with disability under the DES program- the

Disability Management Service (DMS) and the Employment Support Service (ESS). The

DMS is for people with disability who do not require long-term workplace support.

As at February 2022 the DMS covered 44% of the DES caseload. The ESS is for people who have a more severe or

profound disability and who are assessed as requiring continued workplace

support. The ESS covered 56% of the DES caseload in February 2022. DES programs can also involve

rehabilitation, capacity building, training, work experience and other

interventions.

In February 2022,

just over half (55%) of the people in the DMS had a physical disability as

their primary disability. The largest primary disability type in the ESS was people

with psychiatric conditions (42%).

Open employment service providers

In February 2022 there were 106

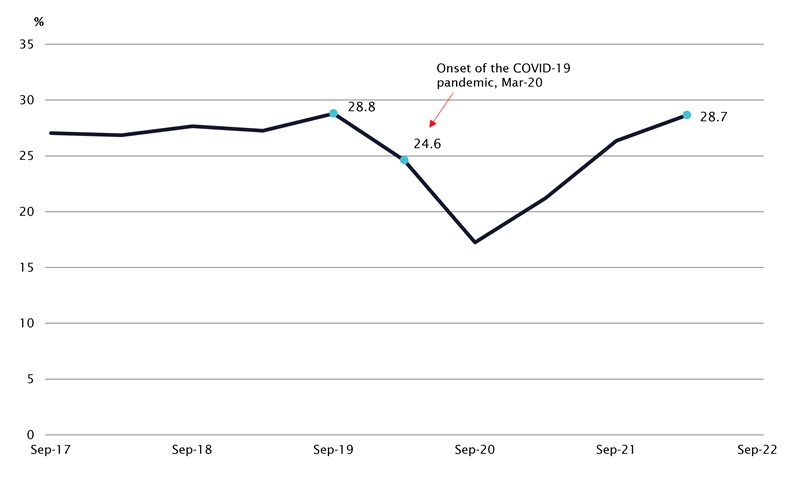

DES providers delivering services to job seekers across almost 3,800 sites. In March 2022 more than a quarter

(29% or 242,484 job seekers) of the total jobactive caseload had a

disability. Figure 3 depicts people with disability as a proportion of the jobactive

caseload for the past 5 years. The size of the jobactive caseload with

disability was fairly consistent until the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in

early 2020, when the total jobactive caseload grew dramatically. This overall growth saw the relative proportion of people with

disability decline. However, this dip was only temporary and the proportion of jobactive

participants with disability has since returned to pre-pandemic levels.

Figure 3 People

with disability as a proportion of total jobactive caseload, 2017 to

2022 (a)

(a) Selected quarters, at March and

September of each year.

Source: National Skills Commission (NSC),

‘Jobactive caseload by selected cohorts time series March 2022’, Employment Regions (jobactive) downloads

(Canberra: NSC, 2022); Parliamentary Library calculations.

Supported employment service providers

Supported employment

services are provided through Australian Disability Enterprises (ADE). ADEs

are generally not-for-profit organisations that employ people with severe or

profound disability who cannot sustain employment in the open labour market but

are able to work at least 8 hours a week. Employers are paid to provide

supports in employment from National

Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) participants’

plan budgets and employees are paid a reduced (pro rata) wage that is meant to

reflect their productivity and competence in performing their work. Pay rates

are largely determined under the Supported Employment Services Award 2020 and using a range of wage assessment tools.

Around 20,000 people with disability are employed in

ADEs, doing work like packaging,

assembly, production, recycling, plant husbandry, garden maintenance and

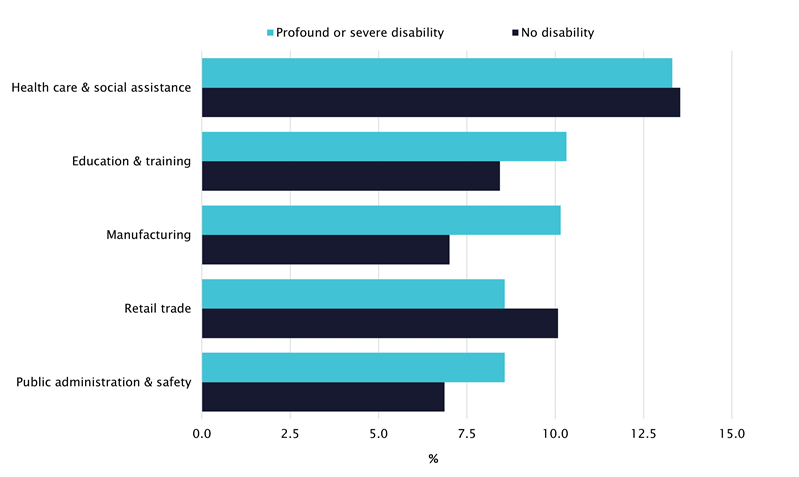

landscaping, cleaning, laundry and preparing food. Figure 4 provides the top 5 industries

of employment for people with a profound or severe disability compared with

people who had no disability. People with severe disability had higher levels

of employment in manufacturing, covering several of the activities undertaken in

ADEs. Industries related to food and administrative tasks were ranked sixth and seventh.

Figure 4 Top 5 industries of employment for

people (15 to 64 years) by selected disability, 2018

Source: ABS, Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia, 2018 (Canberra: ABS, 2019), Table

9.1; Parliamentary Library calculations.

ADEs have recently been the

subject of controversy, with some supported employees complaining in royal commission public hearings about the low rates at which they are paid.

Rates of pay for ADE employees are a longstanding issue.

Recent developments in

open disability employment services

The Department of Social

Services is currently designing a replacement disability employment support

model as the DES program is due to expire on 30 June 2023. The Department’s consultation process included people with disability, employment services providers,

academics, and the wider community. Submissions closed on 1 February 2022.

The DES replacement program

is taking place in the context of broader reforms to Australia’s

publicly-funded employment services system. jobactive is to be replaced

by Workforce Australia from 1 July 2022. This program will see the most job-ready and

digitally literate of job seekers use self-service arrangements, while more

disadvantaged job seekers will receive intensive face-to-face services. Digital

employment services have already been rolled out nationally in response to the

COVID-19 pandemic, and from 1 January 2022, DES-program job seekers have had

the option of accessing employment services and fulfilling their mutual

obligation requirements online.

The Community Development Program, which delivers employment services to job seekers in

remote Australia (primarily Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people), is

also to be replaced by a new Remote Engagement Program, to commence in 2023.

Other relevant

developments include the:

Disability Employment

Services program review

A mid-term review of the DES program was conducted by the Boston Consulting Group from May

to August 2020. The review involved analysis of both the efficacy and efficiency

of the program, and the 2018 program reforms. The reforms sought primarily to

improve participant choice and control, expand DES program coverage, and reduce

the incidence of ‘creaming and parking’- practices through which providers boost

their employment outcome payments by selecting job seekers who are more likely

to find and keep work (creaming) and collect administration fees for harder-to-place job seekers but offer them little or no assistance in finding work

(parking). The review was originally scheduled for December 2020 but was brought

forward due to significantly increased program costs that the review argued were

not matched by a commensurate rise in employment outcomes.

In the 2 or so years

following the 2018 reforms, the DES caseload was found to have risen by 46%.

This contributed to program expenditure increasing from around $800 million in

2017–18 to $1.2 billion in 2019–20. The review found that during the same

timeframe there had been a decline in overall employment outcomes (jobs secured

and employment duration), and that the average cost of achieving these outcomes

had increased by around 38%. The review argued the reduction in employment

outcomes could not be attributed to broader labour market conditions.

The review findings have

been contested by some DES providers. For example, the CEO of Disability Employment Australia suggested the review was ‘deeply flawed’ as a result

of having investigated employment services in the middle of the COVID-19

pandemic, when unemployment was at record high levels. Subsequent DES outcome reports indicate that employment outcomes of program

participants have increased following the easing of COVID‑19

restrictions.

The review identified challenges

for the DES program, including limitations in service quality due to providers’

lack of disability expertise, and the complexity of the system rules that

inhibit providers’ ability to be flexible and innovative or tailor their

support to the needs of individual job seekers. The review was also critical of

the lack of integration and clear pathways between the NDIS and the DES

program, ‘despite their common program goals’ (p. 85).

The review proposed several

recommendations and options to improve DES program performance and ‘restore the

sustainability of DES program caseload and expenditure’ (p. 6). These include:

- better targeting program support to job

seekers who need it the most and who are most likely to benefit from work

- realigning provider incentives to

prioritise employment (rather than education) outcomes

- improving program management ‘with informed

decision making and oversight’

- enabling providers to more easily enter and

exit the market

- enabling and encouraging providers to

exercise flexibility and innovation in the delivery of services

- increasing the amount of time providers are

able to spend assisting job seekers by optimising compliance and administrative

requirements

- allaying employer concerns about employing

people with disability and better assisting them to do so (pp. 7–9).

Consultation on a new disability employment

services model

Over a hundred submissions

were made in response to the department’s consultation paper on a new disability employment support model. While there was

substantial diversity in the responses, there were also some areas of general

agreement.

Some DES service providers

took issue with the findings of the DES review, arguing that the program is

largely effective and should be improved through incremental, evidence-based

reform. However, most submissions maintained that the program is not fit for

purpose and needs to be redesigned. Many submissions expressed concern that the

reform process was being rushed and suggested the current DES contract should

be extended by at least 12 months.

Broadly speaking,

submissions agreed that access to specialist disability employment services

should be made available to all people with disability, irrespective of whether

they are in receipt of government-provided income support. Many expressed

reservations that job seekers assessed as having a greater capacity to work will

be diverted towards Workforce Australia and self-service. There was also a

consensus that a new DES model should be a person-centred model with a

strengths-based approach.

Many submissions argued

that the new model should move away from a ‘work first’ approach towards one

that concentrates on realising long-term sustainable outcomes for job seekers

with disability. Such an approach could reward innovative models of assistance

that are more effective for people with disability. Suggestions included

customised employment, through which jobs are tailored to fit the skills,

interests, strengths, and support needs of a person with disability, while also

meeting business needs.

Several submissions argued

more emphasis on demand-side employment of people with disability is required.

It was suggested that governments could serve as role models- employing more

people with disability themselves, as well as funding research, projects and

innovative initiatives to improve attitudes towards people with disability. Increased

government engagement with employers to develop their confidence and capacity

to employ people with disability was also advocated.

While the NDIS and JobAccess can provide a wide

range of supports to move people with disability into employment, access to

these programs is limited. Submissions argued that greater knowledge of, and

access to, such employment supports could help both job seekers and employers.

Similarly, closer alignment between the new model and the NDIS could help job

seekers to gain and maintain employment.

Many submissions argued mutual

obligation requirements are counterproductive, serving as a barrier for job

seekers to gain employment; and punitive, given the lack of available jobs, especially

for people with disability. If mutual obligations are to be retained in the new

model, these submissions recommended that the compliance function (monitoring

adherence to these requirements) be shifted from employment service providers

to Services Australia or some other third party. Submissions argued that this

shift could improve relationships between job seekers and providers and

potentially lead to better outcomes.

Concluding comments

While well-designed and

well-funded employment programs can and do help job seekers to gain employment,

economic conditions are arguably a more significant determinant of employment

outcomes.

Disadvantaged job seekers,

including people with disability, are disproportionately affected by economic

downturns, such as the recent recession triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic.

If job seekers with

disability are to benefit from the current economic recovery, submissions to

the consultation on a new disability employment services model suggest that

this will require a strong focus on demand-side strategies and working with

employers to identify and create employment opportunities.

Further reading

Australian Human Rights Commission, Willing to Work, report of the National inquiry into employment discrimination against older Australians and Australians with disability, (Sydney: Australian Human Rights Commission, 2016).

Alexandra Devine et al., ‘Australia’s Disability Employment Services Program: Participant Perspectives on Factors Influencing Access to Work’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 21 (31 October 2021).

Katharina Vornholt et al., ‘Disability and Employment- Overview and Highlights’, European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 27, no. 1 (2018): 40–55.

Karen Soldatic, Dina Bowman, Maria Mupanemunda and Patrick McGee, Dead Ends: How Our Social Security System is Failing People with Partial Capacity to Work, (Fitzroy, Victoria: Brotherhood of St Laurence, 2021).

Back to Parliamentary Library Briefing Book

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.