Gregory O’Brien, Statistics and Mapping

Key issue

Australian Government debt has increased to levels not experienced since the 1950s as economic support during the COVID-19 pandemic led to increased budget deficits. As interest rates in Australia and globally have started to increase in response to recent inflationary pressures, both the size and servicing of this debt will be an issue for future Australian governments.

In Australia, and in countries around the world,

government economic support packages in response to the COVID-19 pandemic have

led to large increases in government debt, continuing a trend of increasing

government debt since the global financial crisis (GFC). Over the pandemic, Australian

Government gross debt increased from $534.4 billion in March 2019 to $885.5 billion in April 2022 and is now at the

highest level relative to GDP (gross domestic product) since

the 1950s when debt accrued during the Second World War was still on the

Australian Government balance sheet (p. 8).

This article provides an overview of the structure

of Australian Government debt, recent trends in the total amount of Australian

Government debt outstanding, international comparisons of government debt, and

the relationship between government debt and interest rates.

Australian Government debt issuance and key terms

Australian Government debt is closely linked with

the Australian Government Budget. Government spending is funded either through

receipts- primarily taxes- or through borrowing. In the Budget, the difference

between receipts and payments is referred to as the cash balance and has been

in deficit (payments have exceeded receipts) since 2007–08. These deficits have

led to a steady increase in the level of Australian Government debt.

The Australian

Office of Financial Management (AOFM) manages Australian Government debt

issuance. The AOFM issues 3 types of debt securities, collectively known as

Australian Government Securities (AGS):

- Treasury bonds: medium to long-term debt

securities that pay interest at a fixed annual rate every 6 months. These are

the largest type of AGS, representing 92.8% of AGS on issue as of 20 May 2022.

- Treasury indexed bonds: medium to

long-term debt securities that include adjustments for inflation, as measured

by the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Both the capital value and the interest

payments are adjusted quarterly based on changes in inflation. These

represented 4.1% of AGS on issue as of 20 May 2022.

- Treasury notes: short-term debt

securities with maturations up to one year. These represented 3% of AGS on

issue as of 20 May 2022.

The total face value of AGS on issue at a given

point in time, which represents the total amount that will need to be repaid

when all extant AGS mature, is used as a measure of gross debt in the Budget. The AOFM publishes a weekly figure for total

AGS on issue, broken down into the 3 types described above, as well as more

detailed information in its data hub.

While gross debt is a good representation of the

total magnitude of outstanding debt, it may not be the best measure for

analysing debt sustainability depending on the financial assets available to

service or pay off this debt. For this reason, the

Budget also provides figures for Australian Government net debt,

defined as ‘the sum of interest-bearing liabilities less the sum of selected

financial assets (cash and deposits, advances paid and investments, loans and

placements)’ (p. 347). These financial assets are primarily held in

government investment funds, such as the Future Fund.

Whether gross debt or net debt is a better measure

of government indebtedness will depend on the context of the analysis. The

difference between these measures is described in more detail when looking at

international comparisons of government debt below.

Trends in Australian Government debt

The

Budget provides historical data for a range of budget aggregates back to 1970–71

in the Historical Australian Government Data statement of Budget paper no. 1 (Statement 10 in 2022–23). When comparing levels

of debt across long periods of time, it is useful to convert the dollar values

of debt into a relative measure, usually the ratio to GDP, to control for the

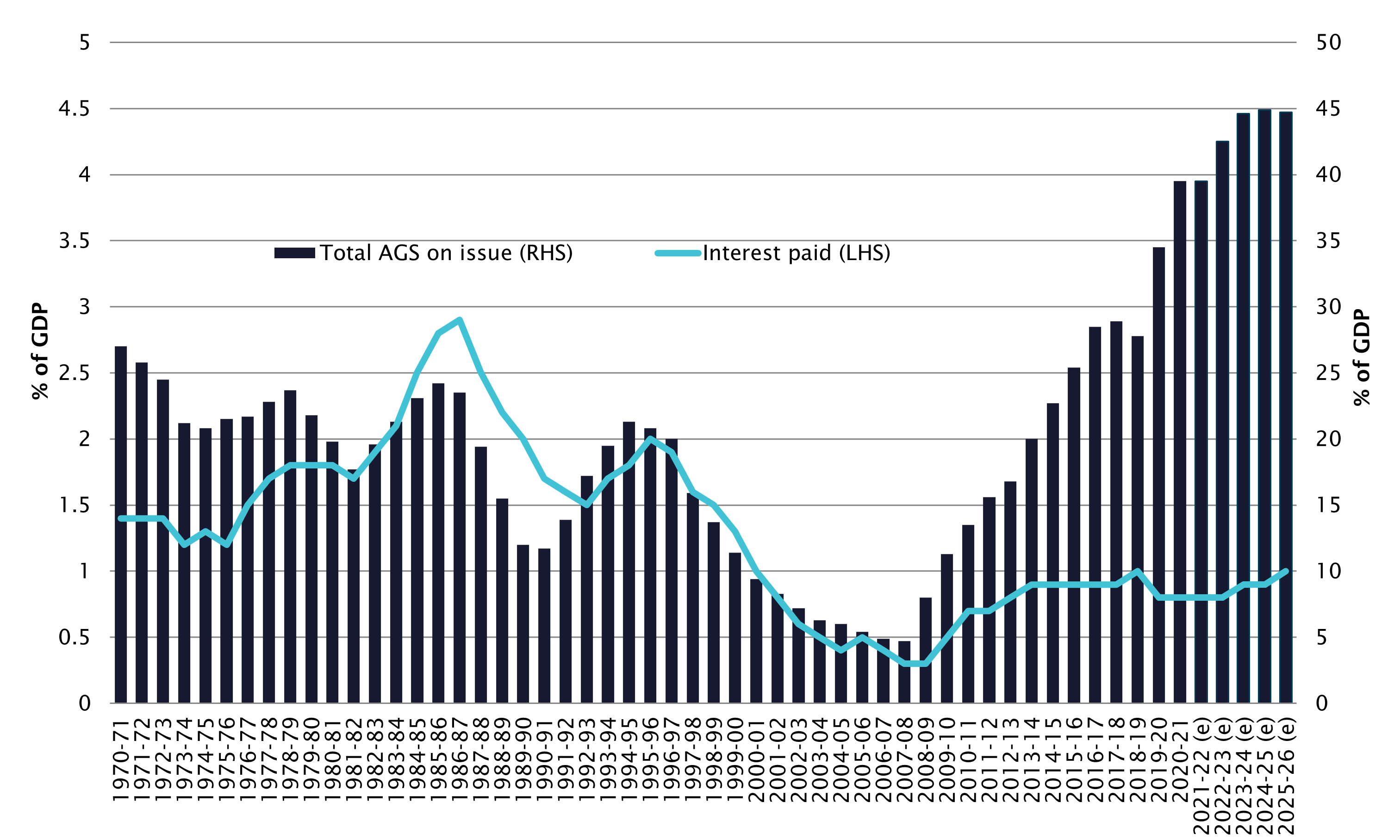

impacts of price changes across the economy. Figure 1 below shows gross debt,

represented by the total face-value of AGS outstanding, as a ratio to GDP over

the last 50 years with the Budget estimates through to 2025–26 and the interest

payments on this debt for the same period, also as a ratio to GDP.

Figure

1 Australian Government total AGS on issue (gross debt) and interest

paid

Source: Australian

Government, Budget

Strategy and Outlook: Budget Paper No. 1: 2022–23, p.348.

This graph shows that Australian Government debt

fluctuated around 20% of GDP from the early 1970s to the mid-1990s with one

period of substantial falls in the late 1980s. Government debt then trended

down between the mid-1990s and the GFC in 2007–08, as the Howard Government

prioritised debt repayment and budget surpluses. From 2008–09 in the wake of

the GFC and associated government economic support packages, government debt

has steadily increased as a ratio to GDP, with 2018–19 the only financial year

over this period which saw a fall in this measure. The

2022–23 Budget forecasts government debt to increase over the next few years

before falling slightly in 2025–26 (p.348). In dollar terms, gross debt is

forecast to increase to over a trillion dollars in 2023–24, reaching a peak

over the forward estimates of $1.193 trillion in April 2026. While current and

forecast debt to GDP ratios are high relative to recent history, they

are still well below the peak reached following the Second World War of over

120% of GDP (p.8) (see

Figure 2).

Figure 2 Australian Government

gross debt to GDP ratio

Sources: pre-1970:

A. Barnard, Source Papers in Economic History via Treasury and The Conversation; post-1970: Australian

Government, Budget Strategy and Outlook: Budget Paper No. 1: 2022–23, p.348.

Note: There are differences in methodology

between the sources, so some care should be taken in comparing recent and

historical figures. The figures for 2021 - 22 to 2024 - 25 are Budget estimates.

These increases in the level of Australian

Government debt since the GFC have not seen a commensurate rise in the amount

of interest paid on this debt because interest rates on Australian Government

debt fell over the period, largely offsetting the increase in the level of

debt. This period of low interest rates has seen interest payments stay at

historically low levels, around 1% of GDP, which is less than half the amount

paid in the 1980s despite the current level of debt being twice the level of

that period.

Interest rates on

Australian Government debt have started to rise in 2022 and have continued

to rise since the 2022–23 Budget was released in March. This increase has been

common to many countries globally in response to inflationary pressures and tightening

of monetary policy by central banks. If interest rates stay above the level

forecast in the Budget, interest payments will increase over time as new debt

is issued at these higher rates and existing debt that was issued at lower

historical interest rates matures and is refinanced.

International comparison of General Government debt

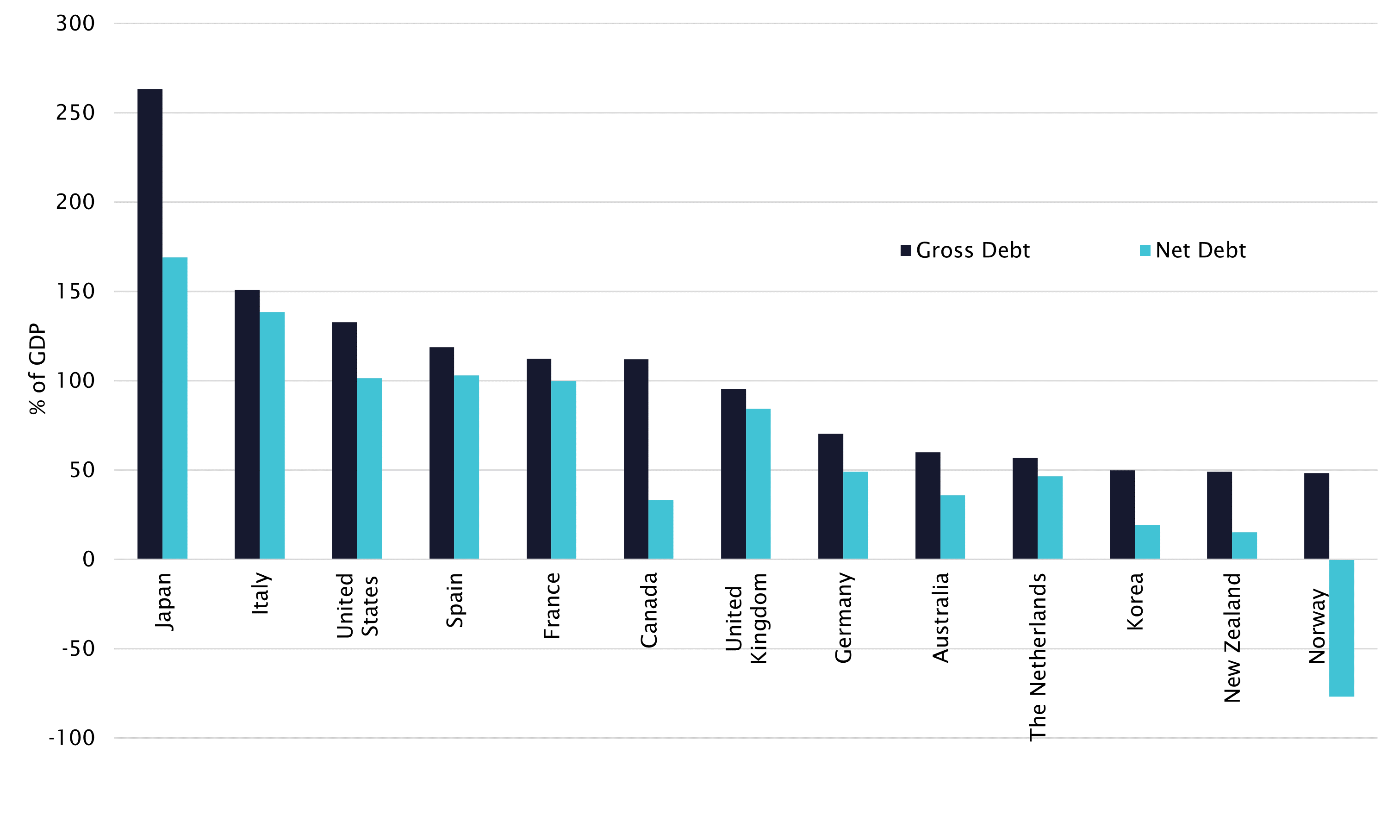

Despite increases in Australian Government gross

and net debt since the GFC, levels of both remain relatively low when compared

to other countries. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) publishes data on

General Government sector gross and net debt across countries. The IMF approach

includes all levels of government (which, in Australia, includes Commonwealth, state

and local governments), which allows more meaningful comparison across

countries with different structures of government. Figure 3 shows IMF estimates

of gross debt and net debt for 2021 across several advanced countries from the IMF’s fiscal monitor 2022 publication.

Figure 3 IMF General Government

gross and net debt (% of GDP) estimates, 2021

Source: International Monetary Fund (IMF), Fiscal

Monitor: Fiscal Policy from Pandemic to War, (Washington, DC: IMF, April 2022).

Figure 3 shows the important difference between

gross debt and net debt when comparing across countries. Countries with

significant financial assets, such as Canada (held by public pension plans) and

Norway (held in a sovereign wealth fund) have much lower levels of net debt

than gross debt once these financial assets are incorporated. This is also

relevant to a lesser extent for Australia, where the $200 billion Future Fund and other smaller

government investment funds have

contributed to a widening gap between gross debt and net debt over time (p. 1).

There is variation across countries in the degree

to which these financial assets are held to meet future specified expenditure

purposes, and some debate as to whether it is appropriate to consider these

assets as offsetting government debt. Gross debt is a more consistent measure

across countries, as there is less variation due to different social security

regimes.

As Figure 3 shows, despite the increase in both

Australian Government net debt and gross debt since 2007–08, the level of

government debt compared to international peers remains relatively low. At just

below 60%, the Australian Government gross debt to GDP ratio is less than half

that of the US, and less than a quarter that of Japan. Both gross

debt to GDP and net debt to GDP ratios are lower than any G7 members, and

similar to mid-sized economies including Korea and New Zealand.

Holdings of Australian Government Securities

Australian Government debt is owned by a range of

Australian and international investors. The AOFM provides information on the

share of AGS on issue owned by non-residents. Under the Guarantee of State

and Territory Borrowing Appropriation Act 2009, the AOFM

was tasked with establishing a Public Register of Government Borrowings. As the AOFM has no powers to compel financial

intermediaries to disclose the beneficial owners of AGS they administer, the

register has limited information on the countries of residence of foreign

owners of AGS.

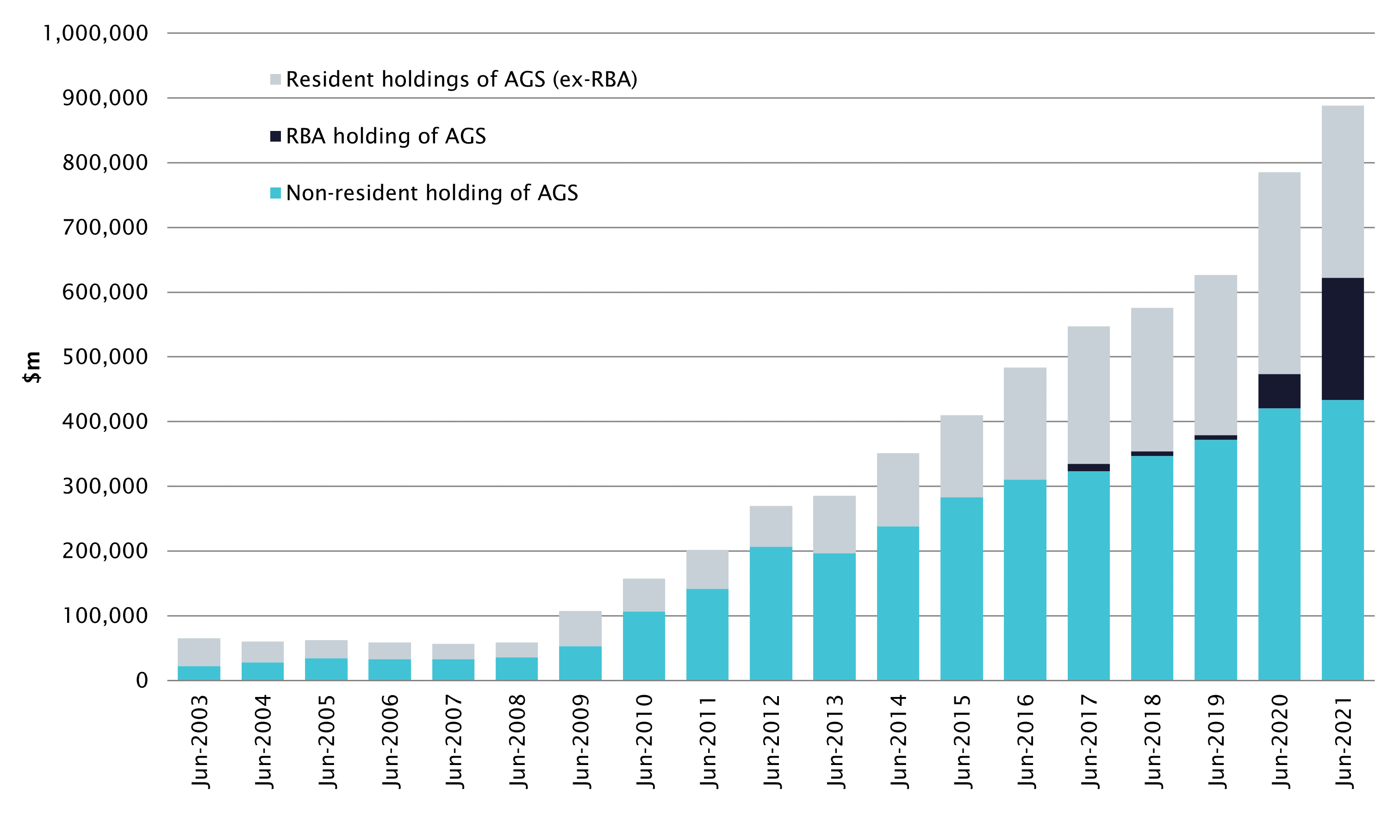

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) started

purchasing significant amounts of AGS on the secondary market as

part of its monetary policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic in order to lower

yields on government bonds and maintain liquidity in bond markets. This has led

to the RBA holding a growing share of the total AGS on issue. The RBA ceased

purchasing AGS in February 2022, and in its May 2022 Statement

on monetary policy decided:

[…]

the Board will not reinvest the proceeds of maturing government bonds and

expects the Bank’s balance sheet to decline significantly over the next couple

of years as the Term Funding Facility comes to an end. The Board is not

currently planning on selling the government bonds that the Bank has purchased

during the pandemic. (p. 3)

This decision means that RBA ownership of AGS

should slowly recede as the existing AGS owned by the RBA mature. As total

outstanding AGS is not forecast to decline, these maturing bonds will need to

be absorbed by the resident and non-resident markets for AGS. Given the

duration of these bonds, this process is likely to slowly occur over the next

decade.

Figure 4 below shows the ownership of AGS by non-residents,

the RBA, and other domestic owners. The chart shows resident holdings of AGS

have steadily increased over the last decade, while non-resident holdings have

fallen as a proportion of the total, and RBA holdings increased. The reduction

in the proportion of AGS held by non-residents reduces the risk of interest

rate volatility associated with capital flight, when non-resident investors sell

overseas assets and repatriate the money, often in response to market

volatility.

Figure 4 Resident, RBA, and

non-resident holdings of AGS, 2003–2021

Source: Parliamentary calculations based

on Australian Office of Financial Management, Non-Resident Holdings of AGS,

and Reserve Bank of Australia, Holdings of Australian

Government Securities and Semis

Government debt sensitivity to interest rate

changes

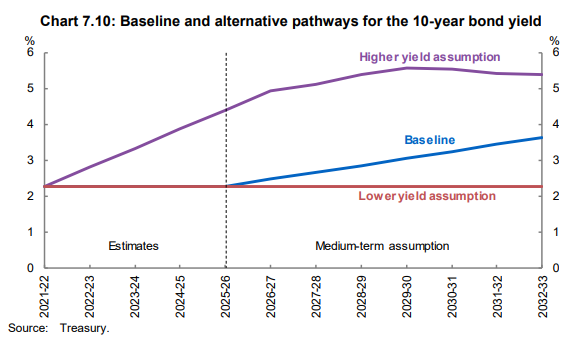

The Australian Government Budget provides

sensitivity analyses to show how varying certain important assumptions (particularly

the iron ore price and yields on 10-year government bonds) would impact on the

economic and fiscal forecasts contained in the Budget. For the 2022–23 Budget,

the sensitivity analysis is contained in Budget

paper no. 1, statement 7: forecasting performance and sensitivity analysis.

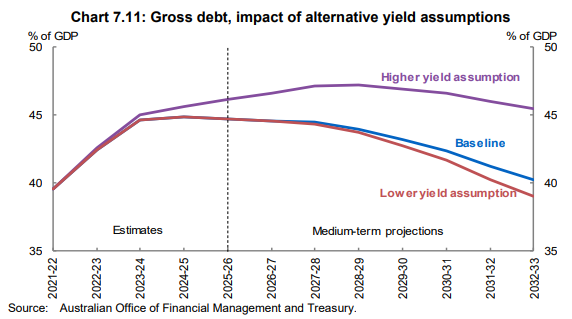

Yield sensitivity analysis models the impact on the

gross debt to GDP ratio if interest rates over the medium term differ from

those assumed in the Budget (the baseline forecast) while maintaining all other

forecasts. The interest rate on 10-year treasury bonds is used as the benchmark

rate. Figure 5 below shows the path of interest rates used by Treasury in the

higher yield and lower yield scenarios in the left panel, and the impact these

higher or lower yields would have on the forecast gross debt to GDP ratio in

the right panel. If interest rates follow a higher yield path than the Budget

forecasts, then the gross debt to GDP ratio will continue to rise for longer

and fall slower than is forecast in the Budget.

Figure 5 Yield Sensitivity

Analysis from Budget 2022–23

Source: Budget

Strategy and Outlook, Budget Paper No. 1: 2022–23, pp. 215–216.

The market

interest rate on 10-year Treasury Bonds in mid-May 2022 is over 3.25% and

reached 3.5% for several days in early May 2022. If interest rates stay at

levels above the level of 2.2% forecast in the Budget in March 2022, the gross

debt to GDP ratio would be expected to be higher than the levels forecast in

the Budget. However, it is important to note that the weighted average cost of

borrowing on Australian Government debt responds slowly to changes in market

interest rates, as the fixed-term nature of treasury bonds means that only new

issuance (including the rolling over of maturing bonds) pays the higher current

interest rate while the existing stock of debt continues to pay interest at the

rate set when that debt was issued.

The sustainability of government debt

The increase in government debt to levels not

experienced in generations raises questions about the sustainability of this

level of debt. While there is no objective level of government debt to GDP

which is problematic, there are several factors worth considering when

analysing the sustainability of government debt.

When considering the Budget ramifications, reducing

the debt to GDP ratio does not necessarily require Budget surpluses. If

economic growth outstrips growth in the level of debt, then the debt to GDP

ratio will fall even if the Budget is in deficit. As the

Budget notes:

From a fiscal sustainability perspective, it

is the difference between nominal yields and nominal economic growth that

matters. If higher yields are accompanied by an economy growing at a faster

rate than the rate on government borrowing, this may be sufficient to improve

debt as a share of the economy over time, all else being equal. (p. 215)

The Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) provides a Fiscal

Sustainability dashboard as part of its fiscal projections and

sustainability publications, which models gross debt to GDP ratios out to 2061

based on various scenarios for GDP growth, the Budget cash balance, and

interest rates.

Whether Australian Government debt is, or will

become, a problem depends on the future path of interest rates, economic

growth, and the Budget balance. Interest payments on Australian Government debt

reduce the amount of money available in the Budget for expenditure on government

services, or requires additional debt to be raised to fund these activities. However,

both international experience and Australian history show that countries can have

higher levels of government debt than are currently prevalent in Australia for

long periods of time without risking default or seeing a substantial decline in

their credit ratings.

Further reading

Australian Government, Statement 6: Debt Statement, and Statement 7: Forecasting Performance and Sensitivity Analysis, Budget Strategy and Outlook: Budget Paper No. 1: 2022–23.

Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO), Fiscal Sustainability, (Canberra: PBO, 2021).

PBO, Beyond the Budget 2021–22: Fiscal Outlook and Scenarios, (Canberra: PBO, 2021).

PBO, Net Debt and Investment Funds – Trends and Balance Sheet Implications, (Canberra: PBO, 2019).

Katrina Di Marco, Mitchell Pirie and Wilson Au-Yeung, A History of Public Debt in Australia, (Canberra: Treasury, 2009).

Back to Parliamentary Library Briefing Book

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.